Graphene transistors in high-performance demonstration

- Published

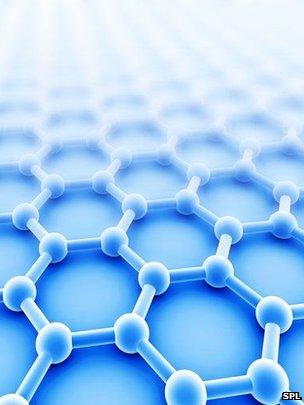

Graphene in its purest state has astounding properties - but to use it, it must be joined to other materials

The hope for the "miracle material" graphene to fulfil its promise in electronics has received a boost - by changing the recipe when cooking it.

Graphene, one-atom-thick sheets of carbon, can carry electric charges far faster than currently used materials.

But it has proven difficult to make it behave as a semiconductor like silicon, or to attach "contacts" to the sheets.

<link> <caption>A study in Nature Communications</caption> <url href="http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v3/n7/full/ncomms1955.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> solves those problems by cooking up graphene from a material called silicon carbide.

Graphene was discovered in 2004 by two University of Manchester scientists - winning them <link> <caption>the 2010 Nobel prize</caption> <url href="http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2010/" platform="highweb"/> </link> in physics.

It has been the focus of intense research efforts to exploit its phenomenal mechanical strength and favourable electronic properties.

Because sheets of it are so thin and it conducts electric charges so well, it is already being used as a crystal-clear "electrode" for solar cells, and will soon find its way into consumer products including smartphones and televisions.

The greatest hope, however, is that it can be used in semiconductor applications, working with or replacing the industry's standard material of silicon.

To make faster computer chips, the industry has been working relentlessly to shrink the individual transistors - and is heading for a physical limit to just how small they can go.

Since charges zip through graphene hundreds of times faster than in silicon, a jump in speed could be made with no decrease in size - but efforts to integrate graphene into chips have been difficult.

One-chip wonder

One problem is that while pure graphene is a particularly good conductor, it is a terrible semiconductor - the kind of material needed to make transistors. While a number of different transistors have been produced using graphene, they have required modifications to it that degrade its electrical performance.

Another issue is the fact that adding metal contacts to graphene - to shuttle electric charges into and out of it - is tricky, and often results in damage.

To tackle both issues, researchers at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany have enlisted the help of a somewhat lesser-known material called silicon carbide - a simple crystal made of silicon and carbon.

In 2009, several members of the same team <link> <caption>reported in Nature Materials</caption> <url href="http://www.nature.com/nmat/journal/v8/n3/full/nmat2382.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> that when wafers of the material were baked, silicon atoms were driven out of the crystal's topmost layer, leaving behind just carbon in the form of graphene.

Graphene transistors have been made before, but they have not achieved graphene's full potential

In the new work, the team joined Swedish research institute Acreo AB, using a high-energy beam of charged atoms to etch "channels" into thin silicon carbide wafers defining where different transistor parts would be.

The team's crucial step was to allow a bit of hydrogen gas in during this process. This affected how the top graphene layer was chemically joined to the underlying silicon carbide: either making a given region conducting or semiconducting, depending on the etched channels.

The way the hydrogen atoms fit themselves into the interface changes the nature of the chemical bonds between the two layers.

Quentin Ramasse, a researcher at the SuperStem Laboratory in Daresbury, UK - whose work recently <itemMeta>news/science-environment-18782151</itemMeta> - called the work "really impressive".

"That's really what they've nailed: controlling that last little bit of bonding to make one type of contact or another," Dr Ramasse told BBC News.

"That's what the hold-up has been, being able to tailor that contact to suit whatever you want to use it for, and have it all in the one chip."

"You read everywhere that graphene is magical for this reason and that, and it's good to be reminded that you can put it in real devices and make it scalable and actually use it for technological applications," he said. "That's a very good step forward."

- Published11 July 2012

- Published8 April 2012

- Published27 January 2012