Nasa's Curiosity rover on course for Mars landing

- Published

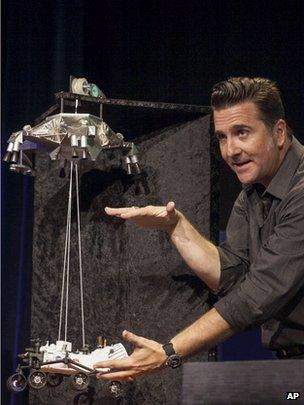

Adam Steltzner expects the new landing system to perform as designed

Nasa says the big robot rover it is sending to Mars looks in excellent shape for its Monday (GMT) landing.

The vehicle, known as Curiosity, external, was launched from Earth in November last year and is now nearing the end of a 570-million-km journey across space.

To reach its intended touch-down zone in a deep equatorial crater, the machine must enter the atmosphere at a very precise point on the sky.

Engineers told reporters on Thursday that they were close to a bulls-eye.

A slight course correction - the fourth since launch - was instigated last Saturday, and the latest analysis indicates Curiosity will be no more than a kilometre from going straight down its planned "keyhole".

The team's confidence is such that it may pass up the opportunity to make a further correction on Friday.

"We are about to land a small compact car on the surface with a trunk-load of instruments. This is a pretty amazing feat getting ready to happen. It's exciting, it's daring - but it's fantastic," said Doug McCuistion, the head of Nasa's Mars programme.

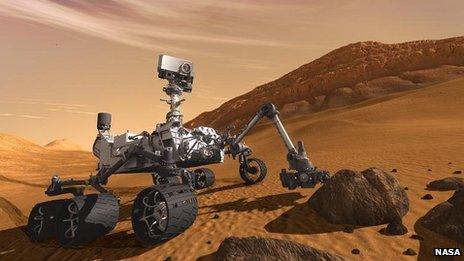

Curiosity - also known as the Mars Science laboratory (MSL) - is the biggest, most sophisticated Mars rover yet.

It will study the rocks inside Gale Crater, one of the deepest holes on Mars, for signs that the planet may once have supported microbial life.

The $2.5bn mission is due to touch down at 05:31 GMT (06:31 BST) Monday 6 August; 22:31 PDT, Sunday 5 August.

It will be a totally automated landing.

Engineers here at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, can only watch and wait.

The vast distance between Mars and Earth means there is a 13-minute lag in communications, making real-time intervention impossible.

Nasa has had to abandon the bouncing airbag approach to making soft landings.

This technique was used to great effect on the three previous rovers - Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity.

But at nearly a tonne, Curiosity is simply too heavy to be supported by inflated cushions.

Instead, the mission team has devised a rocket-powered, hovering crane to lower the rover to the surface in the final moments of its descent.

Adam Steltzner has led this work for Nasa. He said: "It looks a little bit crazy. I promise you it is the least crazy of the methods you could use to land a rover the size of Curiosity on Mars, and we've become quite fond of it - and we're fairly confident that Sunday night will be a good night for us."

The team is also keeping a sharp eye on the Martian weather and any atmospheric conditions that might interfere with the descent manoeuvres.

It is the equivalent of August also on Mars right now, meaning Gale Crater at its position just inside the southern hemisphere is coming out of winter and moving towards spring.

It is the time of year when winds can kick up huge clouds of dust, and a big storm was spotted this week about 1,000km from the landing site. But Nasa expects this storm to dissipate long before landing day.

Science correspondent David Shukman takes a look at a full-scale replica of Curiosity

The first black-and-white images of the surface taken by Curiosity should be returned to Earth in the first hours after touch down, but the mission team do not intend to rush into exploration.

For one thing, the rover has a plutonium battery that should give it far greater longevity than the solar-panelled power systems on previous vehicles.

"This is a very complicated beast," said Pete Theisinger, Curiosity's project manager.

"The speech I made to the team is to recognize that on Sunday night at [22:32 PDT], we will have a priceless asset that we have placed on the surface of another planet that could last a long time if we operate it correctly, and so we will be as cautious as hell about what we do with it."

Step by step: How the Curiosity rover will land on Mars

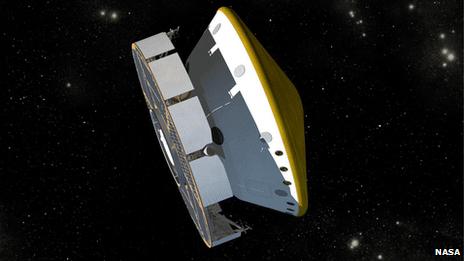

As the rover, tucked inside its protective capsule, heads to Mars, it dumps the disc-shaped cruise stage that has shepherded it from Earth.

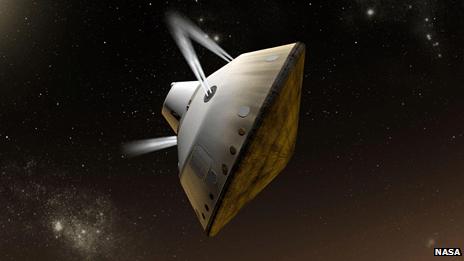

The capsule hits the top of the atmosphere at 20,000km/h. It ejects ballast blocks and fires thrusters to control the trajectory of the descent.

Most of the entry vehicle's energy is dissipated in the plunge through the atmosphere. The front shield heats up to more than 2,000C

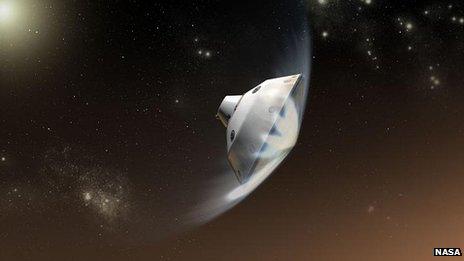

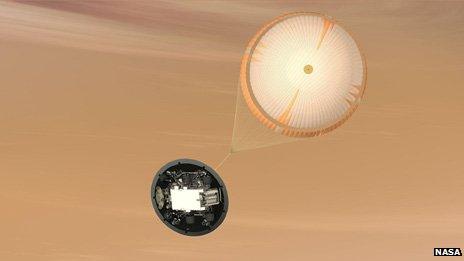

The parachute deploys when the capsule is about 11km above the ground but still moving at supersonic speed

A key event is the dropping of the heat shield - this permits imaging and radar instruments to monitor the approaching surface

At about 1.5km above the ground and still moving at 80m/s, the rover and its sky crane drop away from the parachute and capsule backshell

Rockets on the sky crane slow the descent to 1m/s; cords spool the rover to the surface; the cords are then cut and the crane flies away to a safe distance

The rover is equipped with a nuclear battery and should have ample power to keep rolling across the Martian surface for many years

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published30 July 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published26 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published22 July 2011