Inside the world’s most ‘impossible’ science project

- Published

- comments

Reporting assignments in the Middle East often involve great danger - think of Syria and Gaza. Others run into bureaucratic obstruction. But the Sesame science project in Jordan is so bizarre it presented challenges of a wholly unexpected kind.

The first was the sheer difficulty of grasping that the story was not the figment of someone's imagination but was actually happening.

We had come to get a look at a "synchrotron" facility called Sesame - at its heart, a particle accelerator not unlike Europe's Cern - coming together in Jordan. A news story on the Sesame project explains the science it aims to do, but that is not the striking thing about it.

On the scale of surprises that take a very long while to sink in, Sesame, external is off the scale: common sense would scream at you that it just should not be feasible.

At first sight the project to build a shared research centre in the Middle East sounds like a far-fetched and wholly unrealistic fantasy of the kind John Lennon conjured up in "Imagine…"

The scenario goes as follows: take one of the world's most unstable regions, pick some of the countries that are most violently opposed to each other and then bring them together under one roof to do science.

The list of countries involved looks utterly improbable: it includes Jordan, Turkey, Bahrain and Egypt - so far so normal. But then add Iran and - amazingly - Israel too.

And they actually have to meet each other every year to discuss plans including the fraught question of contributions.

This is Sesame in a nutshell: an extraordinarily bold idea to plant a world-class science facility - a synchrotron light source - in the heart of the Middle East for researchers from anywhere from Cairo to Tel Aviv to Tehran.

So the first obstacle is getting past one's own natural incredulity that anything like this could ever get off the ground.

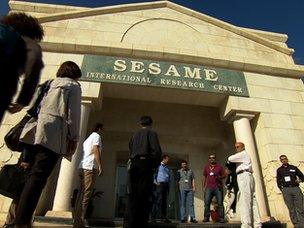

But the fact is that it has. Sesame not only has a rather grand new building, near the village of Allan in the hills northwest of Amman; it also has the first components that will generate and accelerate a flow of electrons. If all goes well, sometime around 2015, the energy from those electrons will be harnessed to help peer into the world of the microscopically small.

Diplomatic minefield

There are builders hoisting vast concrete blocks into place for the radiation shielding. Scientists are running tests on the first batches of equipment. Administrators are planning budgets and new appointments and all the intricate detail of a highly technical undertaking.

Scientists from many countries are working on the project

And that leads to the second challenge of reporting on Sesame, that of picking a path through the infinite sensitivities of a diplomatic minefield.

To give you a few examples of the tensions among participating countries: Turkey and Cyprus do not recognize each other; Iran and Pakistan do not recognise Israel and Eqypt and Jordan face their own internal difficulties. Meanwhile, Iranian scientists have been jailed or assassinated (including two associated with Sesame). This is no ordinary science project.

Yet somehow, after a decade of huge uncertainties about funding and endless doubts about who will take part, the people making this project work have found a way of rubbing along.

We timed our visit, earlier this month, to coincide with one of the annual rounds of meetings of scientists and officials - but we had no idea whether anyone would welcome the prospect of a television camera in their midst, let alone talk to us.

Even the organisers were not sure, and they certainly did not want us barging in with a camera uninvited and risk wrecking everything. As I may have mentioned, this was no ordinary story.

Given the hostility felt towards Israel, for instance, would any Arabs or Iranians ever consent to being pictured in the same room as Israeli scientists? If we were seen talking to one, would others boycott us? And, worst of all, would our filming put anyone in danger back home? Not everyone in Iran or Israel or the Arab countries likes the idea of their people fraternising with the other side.

Addressing a meeting

There was only one way to find out: I offered to stand up at one of the meetings and ask. I was given my chance between a talk on Sesame's potential to examine the nanometre-scale structures of proteins and one on plans for high-powered computing to handle all the data - a journalistic interlude amid high science.

In front of me was a sea of nationalities - a few men in suits, the Iranian men characteristically tie-less, women in different styles of head-scarf, some very covered, others less so.

We were in the basement ballroom of a hotel, gloomy after the bright sun outside. From the room next door I could hear lively voices; ironically, it turned out to be a medical training session by a British wound-healing company.

As I described why I wanted to report on Sesame, and how we planned to do that, I was relieved to see a few heads quickly nodding in approval.

But I then asked our most difficult question: whether anyone did not want to be filmed. The room was silent. This was a key moment. Our coverage would be determined by the outcome.

Long way to go

The conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza had not quite started, but tensions were high over Iran's nuclear programme. Newspaper reports had just revealed that Israel had been ready to bomb Iran's nuclear sites two years ago. And the Iranian government has never withdrawn its pledge to destroy Israel.

The centre plans groundbreaking work

I asked again, fully expecting at least a handful of people, probably the Iranians, to raise their hands in polite objection. But no-one did. Against every expectation, against all the odds, here was a group of people from a region wracked by hatred and conflict who were not only here for the science but also were proud of it.

I nodded to cameraman Matt Goddard and producer Kate Stephens: we were on. Filming could begin. No one was keen to be filmed befriending the Israeli. But everyone was happy to be interviewed. We were holding our breath in disbelief.

I'm aware this could all appear ridiculously naive. There are countless scenarios that could kill Sesame before it's complete. Iran and Israel could start a war. Jordan's current unrest could make travel there dangerous. One of the contributors' cheques could bounce.

The richest Arab countries, like Saudi Arabia, have always stayed away, presumably because of Israel's involvement. The US sends an observer but no money because Iran is taking part.

But somehow, astonishingly, a dream to use science as diplomacy is alive. Enough people are determined to push for it. The world's most impossible science project is really taking shape.

'Open Sesame: science in the desert' will be on BBC Radio 4 tonight at 8pm

- Published26 November 2012

- Published26 November 2012

- Published26 November 2012