Why did the Antarctic drilling project fail?

- Published

- comments

A few members of the team that attempted to search for life in Antarctica's Lake Ellsworth are already beginning a long, sad and disappointed journey home.

The rest will be gone, along with all the equipment, the stores and a union jack, in a few weeks' time, leaving no trace of this daring mission to reach beneath the ice.

The most exciting science often carries the greatest risk and, despite three years of planning, this is a gamble that has not paid off.

The talk from the team is brave, of course - of lessons learned, of valuable experience, of regrouping to try again.

But the voice of the chief scientist, Prof Martin Siegert, conveys the painful combination of exhaustion and failure that marks all projects that go wrong.

And it carries memories of another brave British attempt to search for life, on another planet almost 10 years ago.

The aim in Antarctica, external was to use a hot-water drill to reach down through the two miles of the ice sheet to open a borehole to the waters of Lake Ellsworth below.

The plan had estimated that five days of drilling would do the job and would then allow for 24 hours before the hole re-froze to lower devices into the water and sediment.

In theory, by now, the team should have been hauling to the surface precious containers holding samples from a lost and hidden world isolated for up to half a million years.

Instead the hot water drill did not manage to reach into the depths as required.

The drilling plan called for the creation of a large cavity in the ice to act as a reservoir and as a means of regulating the pressure from the lake below.

The cavity was formed - so far, so good - but when the main borehole was drilled, just 1.5m from the hole leading to the cavity, it could not make a connection down below.

The team assumed that the borehole would descend vertically but maybe it veered off slightly which meant that an accurate aim - and connection - was not possible.

And without being able to hook up the main borehole to the cavity, countless gallons of hot water were wasted in the attempt and the limited fuel stores rapidly depleted.

On Christmas Eve, a fateful decision approached. This £8m project had coped with equipment breakdowns and last-minute hurdles, ferocious weather and utter remoteness.

At one stage, an electronic component the size of a thumbnail - essential to the running of the main boiler - had to be flown out all the way from Britain.

But in the end it was the drilling that proved the project's undoing: it simply could not continue because fuel was running low.

By the evening, gathered in the main tent, the team had to face an awful moment: there was no option but to pull the plug.

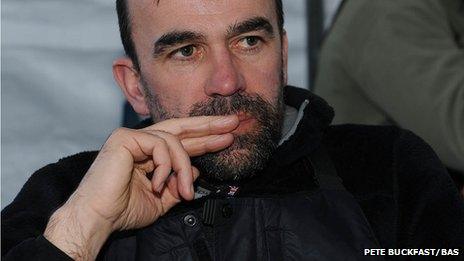

Martin Siegert, chief scientist on the drilling project

The chief scientist, and main driver behind the project, Prof Martin Siegert, prepared a few words for on-site cameraman Pete Bucktrout. It was '"Game over".

Last summer, when I first met Prof Siegert, I was too polite to remind him of what had happened to another British science project, the Beagle 2 mission to Mars, external, the spacecraft named after the ship that had carried Charles Darwin.

That clever piece of engineering was a tiny lander that was carried to the Red Planet in 2003 on board the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter.

Back then many of us gathered with Beagle's mastermind, Prof Colin Pillinger, to wait to hear the first signal that the spacecraft had touched down safely. The signal never came; Beagle went missing, presumed dead.

So it was to my surprise that Prof Siegert himself brought up the parallel, comparing that audacious attempt to search for life on Mars with his own bid to seek it in the unlit depths beneath the Antarctic ice sheet.

At the time, in that summer conversation, neither of us realised an eerie coincidence. Beagle crashed on Christmas Day 2003; the Lake Ellsworth mission was abandoned on Christmas Eve 2012.

Over a crackly satellite phone connection today, Prof Siegert managed a laugh at the timing.

But there is a difference between the two projects. Funding was never found to launch another Beagle to Mars while it is likely that another attempt will be made on Lake Ellsworth.

The team will work on a revised plan next year. Another go may be tried in four or five years' time.

For the moment, though, the fundamental question that drove both missions remains unanswered: what is the limit to where life is possible?