Sleep problems could jeopardise future missions to Mars

- Published

The Mars500 crew - pictured here before the mission - were to experience isolation and depression during their simulated journey

Some of the first results from a simulation of a mission to Mars show that some of the crew experienced isolation and mild depression.

Research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external suggests differences in the sleep patterns of the crew caused problems.

The findings suggest that not all current astronauts will be suited to interplanetary travel.

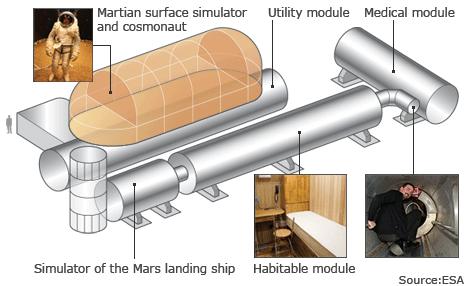

The Mars500 project investigated how crews would cope on a real mission.

Prof Mathias Basner, of the University of Pennsylvania - who was involved in the sleep study - says that the findings show that astronauts for any future Mars missions should be tested for their ability to cope without a natural day/night cycle.

"This illustrates that there are huge differences between individuals and what we need to do is select the right crew, people with the right stuff, and train them properly and once they are on the real mission to Mars," he told BBC News.

Currently, no astronaut is in space for longer than six months on the International Space Station (ISS). The aim of the 17 month-long Mars500 project was to study the physical and psychological effects that the much longer journey to Mars might have on future astronauts.

The simulation involved six crew members: three Russians, two Europeans and one Chinese volunteer.

For much of the time, the men had only limited contact with the outside world. Their spaceship had no windows, and the protocols demanded their communications endured a similar time lag to that encountered by real messages as they travel the vast distance between Earth and Mars.

Nearly 100 different experiments were carried out to assess the impact of the journey on the men, and it is only now that the first results are emerging.

The sleep experiment is among the first to show what each crew member went through during their simulated mission.

The researchers found that one crew member lost his natural day/night rhythm completely. Instead of a 24-hour cycle, he slipped into a 25-hour day so after 12 days he was completely out of sync with his fellow crew mates. It was the middle of the night for him while his colleagues were working on the mission.

"You can imagine that that wouldn't be good during a real Mars mission when there are mission critical tasks planned during the day," said Prof Basner.

"He became somewhat isolated. For 20% of the time this crew member was either the only crew member awake or the only person sleeping which could potentially be a problem for team cohesion," he said.

Most of the crew members began to sleep more and become less active as the mission wore on, but one crew member did the opposite. He slept less and less during the mission until he became chronically sleep deprived.

All the crew had to carry out performance tests once a week. The sleep deprived member was responsible for the majority of the errors in the tests.

Another crew member developed a mild depression.

"Two crew members coped really well with this prolonged confinement and isolation," according to Prof Basner.

"But four of them had a problem where you would think you don't want to send someone like this on the mission or if you do, you want to know that this subject is vulnerable and train him or her properly."

Problems manifested themselves at between two and four months and so, the research team suggests, potential interplanetary astronauts could be screened for their suitability by being put through a much shorter simulation than the Mars500 project.

Another problem identified by the researchers was the dim fluorescent lighting which was not bright enough to simulate daylight and no protocol for differentiating between day and night in the simulated spacecraft. It was up to the crew members when to turn the light on and off.

The experiment even simulates surface operations at the Red Planet

"This is one of the take home messages," according to Prof Basner. "There has to be adequate lighting and it has to be strong enough to get the day/night cycle going and the time that the crew exposes itself to the light also has to be optimal."

Dr Kevin Fong, who is an expert on space medicine said that the research confirms that sleep deprivation is likely to be a real problem on future Mars missions.

"It needs to be taken seriously," he said. "Sleep deprivation is going to happen with crews and has the potential to affect mission safety."

Dr Iya Whiteley who is the deputy director at the Centre for Space Medicine, Mullard Space Science Laboratory, said that there were also lessons to be learned for shift workers on Earth.

"Any individual undertaking accurate detailed work without normal day/night cycle will be affected, whether it is the air traffic controller on shift work, or nuclear power workers."

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published21 September 2012

- Published22 September 2012

- Published3 June 2010