Graphene: Patent surge reveals global race

- Published

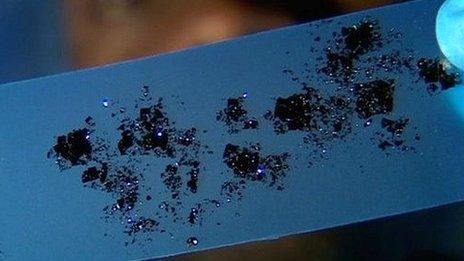

Graphene could find uses in computing, energy, medicine and other fields

A surge in research into the novel material graphene reveals an intensifying global contest to lead a potential industrial revolution.

Latest figures show a sharp rise in patents filed to claim rights over different aspects of graphene since 2007, with a further spike last year.

China leads the field as the country with the most patents.

The South Korean electronics giant Samsung stands out as the company with most to its name.

The figures, compiled by a UK-based patent consultancy, CambridgeIP, highlight how Britain, which pioneered research into graphene, may be falling behind its rivals.

Only identified in 2004, graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms making it the thinnest material ever created and offering huge promise for a host of applications from IT to energy to medicine.

Flexible touchscreens, lighting within walls and enhanced batteries are among the likely first applications.

Early work on graphene by two Russian-born scientists at the University of Manchester, Andrei Geim and Konstantin Novosolev, earned them a shared Nobel Prize in 2010 and then knighthoods.

The material - described as being far stronger than diamond, much more conductive than copper and as flexible as rubber - is now at the heart of a worldwide contest to exploit its properties and develop techniques to commercialise it.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, announced further funding for graphene research last month, bringing the total of UK government support to more than £60m.

The BBC's David Shukman explains how graphene is the thinnest material ever made

But the tally of patents - an essential first step to turning a profit from a substance still based in the lab - shows how intense the worldwide competition has become.

According to new figures from CambridgeIP, there were 7,351 graphene patents and patent applications across the world by the end of last year - a remarkably high number for a material only recognized for less than a decade.

Of that total, Chinese institutions and corporations have the most with 2,200 - the largest number of any country and clear evidence of Chinese determination to capitalise on graphene's future value.

The US ranks second with 1,754 patents. The UK, which kickstarted the field with the original research back in 2004, has only 54 - of which 16 are held by Manchester University.

UK science minister David Willetts, who has identified graphene as a national research priority, said the figures show that "we need to raise our game".

"It's the classic problem of Britain inventing something and other countries developing it."

Most striking of all the figures is that the South Korean electronics giant Samsung leads the corporate field with an immense total 407 patents. America's IBM is second with 134.

Prof Geim says many Western companies lack the ability to pursue research

The chairman of CambridgeIP, Quentin Tannock, told the BBC: "There's incredible interest around the world - and from 2007 onwards we see a massive spike in filings all over the world particularly in the USA Asia and Europe."

But he warned that despite the British government's support, there was a serious risk that the UK may lose out.

"Britain has got a reputation for being very canny, having very good inventors, so the race isn't over.

"But my concern is that in Britain there isn't an appreciation of just how competitive the race for value in graphene is internationally, and just how focused and well-resourced our competitors are.

"And that leads to a risk that we might underinvest in graphene as an area and that therefore we might look back in 20 years' time with hindsight and say 'that was wonderful, we got a lot of value, but we didn't get as much as we should have done'."

The head of graphene research at the National University of Singapore confirmed to me that the material is now the subject of an intense contest.

Professor Antonio Castro Neto said: "It's extremely competitive not only from the point of view of science… but also from a business point of view because many many companies are starting to operate and sell graphene and graphene-related things."

He believes that Britain still has "the potential to compete and be as big as what's happening here in Asia".

"But Asia, especially Singapore, started early. They had the vision to start early - but we still have to see what's going to happen. There are lots of things going on and it will take time to find out who is going to win the race," he explained.

Beyond the horizon

However one of the scientists behind the original work on graphene, Professor Geim, told me that many Western companies lack the ability to pursue research.

"Industry is more worried not about what can be done, but what competitors are doing - they're afraid of losing the race.

The National Graphene Institute is to be built in Manchester at a cost of £61m

"There is a huge gap between academia and industry and this gap has broadened during the last few decades after the end of Cold War, so I try as much as I can to reach to the industry.

"This is what has happened in last 30-40 years. We killed famous labs like Bell labs. Companies have slimmed down so they can no longer afford top research institutes. If something is happening in Korea it's because Samsung have an institute - there is nothing like that in this country.

"They can't see beyond a 10-year horizon and graphene is beyond this horizon."

European efforts may get a boost later this month when the European Commission announces the winners of a prize of one billion euros over 10 years for scientific research.

One of the six shortlisted entrants is a consortium of researchers under the banner Graphene Flagship.

And Mr Willetts, pointing to BP's commitment to establish a $100m advanced materials research facility in Manchester, said Britain could become "a world centre for graphene research" and attract more investment - but he admitted it was a difficult challenge.

Follow David on Twitter, external.

- Published15 January 2013

- Published11 July 2012