Fermi telescope may change to dark matter hunting

- Published

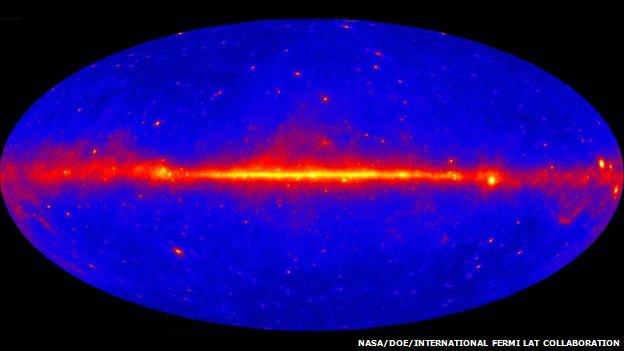

The full sky is seen in the Fermi telescope map; gamma-ray sources abound along the central, galactic plane

The Universe's highest-energy light could finally yield clues to the nature of the "dark matter" that makes up some 85% of the Universe's mass.

The Fermi space telescope, designed to catch gamma rays, has seen hints of evidence for dark matter in high-energy gamma rays seen at the galaxy's centre.

The Fermi team is now opening a call for ideas on changing how it observes.

That may focus efforts on those early hints, opening the possibility to solve one of physics' greatest mysteries.

We only know of the existence of dark matter because of its gravitational effects; true to its name, it cannot be seen because it interacts only very weakly with light or normal matter.

Proving its existence, and learning something about what it is, has been a holy grail for astrophysicists since the 1930s.

Julie McEnery, project scientist for the Fermi mission, said a deepening dark matter mystery has sparked the call for proposals to change the telescope's mission.

"Some of the motivation to explore different observation strategies is from this tentative signal at the centre of the galaxy, but I think even if that wasn't there we would want to go to our community of scientists and ask them, 'based on what you've seen in the data, should we do something different?'," she told the BBC World Service programme Science in Action.

Fermi has been a tremendous success at examining some of the most high-energy processes in the cosmos, publishing a catalogue filled with details of the spinning neutron stars known as pulsars, and a wide array of "active galactic nuclei" - probably supermassive black holes.

But outside the Fermi team, the focus shifted in early 2012, when a pair, external of papers, external on the Arxiv preprint server suggested hints of dark matter within Fermi's data, which are publicly available.

The most popular theory holds that dark matter is made up of relatively heavy particles which, when they encounter one another, "annihilate" with a flash of light that the Fermi telescope can see.

"The nice fact which distinguishes this situation from other similar situations with dark matter candidates is that there are no viable astrophysical alternatives," said Lars Bergstrom, who first proposed this idea in a paper in Physical Review D, external in 1988.

"It is a so-called 'smoking gun' signal of dark matter annihilation," Prof Bergstrom told the BBC.

'Bump hunting'

But the dark matter "line" that those initial papers suggested - and the more than 100 papers that have appeared on Arxiv since on the same topic - is still far from a certainty. As is so often the case in science, more data are needed.

"If we really are seeing evidence for dark matter at the centre of our galaxy, it will be the result of the Fermi mission," Dr McEnery said.

"We'll have found something that physicists and astronomers have been looking for for decades - understanding not just where dark matter is but something more fundamental about its nature, so this is something that we in the Fermi project are keen to pursue."

Astrophysicist Doug Finkbeiner of Harvard University said he was initially sceptical about the early papers.

"I didn't really think there was anything there - to a good approximation, these sorts of 'bump-hunting' adventures are always wrong, so I wasn't expecting to get anything out of this," he told the BBC.

But he went on to publish two, externalpapers, external on the signals and even an attempt to disprove them, external, and he was among the first to raise the idea of changing the way the Fermi telescope observes to a stronger focus on the origin of the purported signal.

In the intervening time, some papers have suggested that the signal might not be as strong as first thought. Dr Finkbeiner wants to be careful that the bid to chase the dark matter mystery isn't at the cost of less speculative science.

"You know, it's a half-billion dollar mission and the data's used by hundreds of people, so you have to take everybody's interests into account here," he said.

"I try to be as sceptical as possible, especially about the things I want to be true - so I'm hesitant to be the guy who says 'hey let's drop everything and go look at this', and then have it turn out to be nothing."

That may yet happen. Or it may simply be that other attempts to pin down dark matter get there first. A range of experiments back on Earth, deep beneath the surface, are aiming to detect dark matter more directly by catching its rare interactions with normal matter.

Prof Bergstrom said that the addition of a fifth telescope to the Hess telescope array in Namibia, due to be completed later this year, could make it able to put this dark matter question to bed in just 50 hours of observation, external.

"We have a very interesting couple of years ahead of us," he said.

The BBC World Service programme Science in Action was first broadcast on 17 January; a schedule of repeat broadcasts can be found here. Or you can listen anytime here or download the podcast here.

- Published20 June 2012

- Published9 January 2012

- Published22 June 2011

- Published13 May 2011