Dark Matter: Experiment to shed light on dark particles

- Published

- comments

BBC World Service science reporter Rebecca Morelle has been inside the Darkside50 experiment

In a man-made cavern, deep beneath a mountain, scientists are hoping to shed light on one of the most mysterious substances in our Universe - dark matter.

The Gran Sasso National Laboratory seems more like a Bond villain's lair than a hub for world class physics.

It's buried under the highest peak of Italy's Gran Sasso mountain range; the entrance concealed behind a colossal steel door found halfway along a tunnel that cuts through the mountain.

But there's a good reason for its subterranean location. The 1,400m of rock above means that it is shielded from the cosmic rays that constantly bombard the surface of our planet.

It provides scientists with the "silence" they need to understand some of the strangest phenomena known to physics.

Inside three vast halls, a raft of experiments are running - but with their latest addition, DarkSide50, scientists are setting their sights on dark matter.

Everything we know and can see in the Universe only makes up about 4% of the stuff that is out there.

The rest, scientists believe, comes in two enigmatic forms.

They predict that about 73% of the Universe is made up of dark energy - a pervasive energy field that acts as a sort of anti-gravity to stop the Universe from contracting back in on itself.

The other 23%, researchers believe, comes in the form of dark matter. The challenge is that until now nobody has seen it.

Dr Chamkaur Ghag, a particle physicist from University College London, explains: "We think it is in the form of a particle.

"We have protons, neutrons and electrons and all these regular normal particles that you associate building things with. We think dark matter is a particle too, it's just an odd form of matter in the fact that we don't perceive it very readily.

"And that is because it doesn't feel the electromagnetic force - light doesn't bounce off it, we don't interact with it very strongly."

Physicists have called these dark matter contenders Weakly Interacting Massive Particles - or WIMPS.

They believe millions of them are passing through us every second without a trace.

But very occasionally one will bump into a piece of "regular" matter - and that is what they are hoping to detect with DarkSide50.

Scientists hope to detect that rare event when a particle of dark "stuff" bumps into regular matter

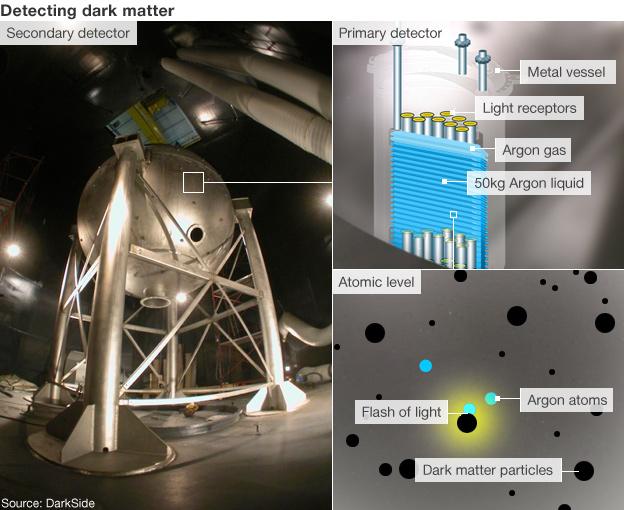

Inside a house-sized tank, a large metal sphere holds a particle detector called a scintillator.

This container is filled with 50kg of liquid argon and a thick layer of the element in its gas form.

"If a dark matter particle comes in and hits the argon, the recoiling atom gets a kick of energy and it quickly tries to get rid of it," says Dr Ghag.

"In argon it gets rid of it by kicking out light; it sheds photons.

"But it also gives charge: some electrons that are liberated from the interaction site. And those electrons drift up into a gas layer, and when they hit the gas and you get another flash of light."

As dark matter particles steam through the detector, scientists hope that a few will collide with the argon atoms. This will generate two flashes of light - one in the liquid argon and another in the gas - which will be detected by the receptors.

Until now, the hunt for dark matter has proved elusive.

Some experiments claim to have seen signals of dark matter in the form of annual modulation.

This is the idea that the number of these particles we should be detecting changes as the seasons change.

That's because as the Earth moves around the Sun, it is moving into a stationary field of dark matter - and for half the year it will be moving against the tide of dark matter - just like driving into the rain. But for the other half it will be moving with this tide and less dark matter will hit.

But other researchers have questioned attributing these seasonal variations that have been detected to dark matter.

The experiments are housed in a cavernous room underground

Other experiments have run for long periods of times without so much as a hint of the stuff.

One, called XENON100, which is also in Gran Sasso, ran for the course of a year, but only saw two "events" - not enough to rule out that this might have been some stray background radiation.

But with DarkSide50, there seems to be a new push to find some answers.

Alongside this experiment, another large detector - LUX - which is in a gold mine in South Dakota in the US will soon be coming online.

And in the next few years, scientists are planning even more ambitions detectors, such as XENON1T and LUX-Zeplin - they are hoping to find the first experimental evidence of these particles.

Aldo Ianni, from the DarkSide50 team, says: "Dark matter is really a major scientific goal at the present time.

"It will help us understand a big fraction of our Universe that we don't understand at the present time. We know there is dark matter - but we have to understand what this dark matter is made of."

Fruitless search?

Professor Stefano Ragazzi, director of the Gran Sasso National Laboratory, hopes that the first glimpse of dark matter will be in his research facility.

"There is competition amongst different experiments - so when you compete you prefer to win rather than coming second or third," he explains.

"The feeling is that dark matter could be just around the corner, so everybody is rushing to be the first to find it."

However, he admits that there is always the chance that these experiments may find nothing at all - and dark matter may not be in the form of WIMPs.

The director of Gran Sasso hopes the first glimpse of dark matter will be made at his facility

Professor Ragazzi says: "We may find that we have the wrong hypothesis… [dark matter] may be something completely different.

"But it may be even more interesting not finding dark matter than finding it."

In the next few weeks DarkSide50 will be fully kitted out, the surrounding tank flooded with purified water, and then the scientists will have to watch and wait.

But Dr Ghag says despite the uncertainties, the potential reward of finding dark matter would be huge.

"If we did find dark matter, then we'd have done would be to solved one of nature's best kept secrets. And that would have been to have figured out what a quarter of the Universe is made of," he explains.

"That would be a revolutionary discovery - it would change our understanding of the Universe, the way it formed, and the way it will evolve."

- Published16 September 2011

- Published7 September 2011

- Published29 June 2011