Lift-off for latest Landsat mission

- Published

The Landsat spacecraft was launched on an Atlas vehicle from the US West Coast

One of the most important space launches of the year has just occurred in California.

It saw the Landsat-8 mission hurtle skywards on an Atlas rocket from the US Air Force base at Vandenberg shortly after 10:00 local time (18:00 GMT).

The spacecraft will maintain the longest continuous image record of the Earth's surface as viewed from space.

It is a record that now stretches back over 40 years - an invaluable tool for studying our changing world.

The latest spacecraft was lifted by the Atlas into a 680km-high polar orbit. It will take about three months for Nasa engineers to test the platform and get it ready for use at its operational altitude of 705km.

"Landsat is a critical asset," said US space agency (Nasa) project scientist Dr Jim Irons.

"Land cover and land use are changing now at rates unprecedented in human history due to an increasing population, advancing technology and shifts in the climate.

"In order for us to adapt to these changes and make sensible decisions about what we do to the surface of the planet, we need the information this satellite series gives us," he told told BBC News.

The entire 40-year image archive is open and free. Scientists around the globe exploit the information in myriad ways - from monitoring the health of crops and the status of volcanoes, to measuring the growth of cities and the extent of glaciers.

One of the uses best known to the general public will be on their phones and computers through Google, which incorporates Landsat data, external into its Earth and Maps applications.

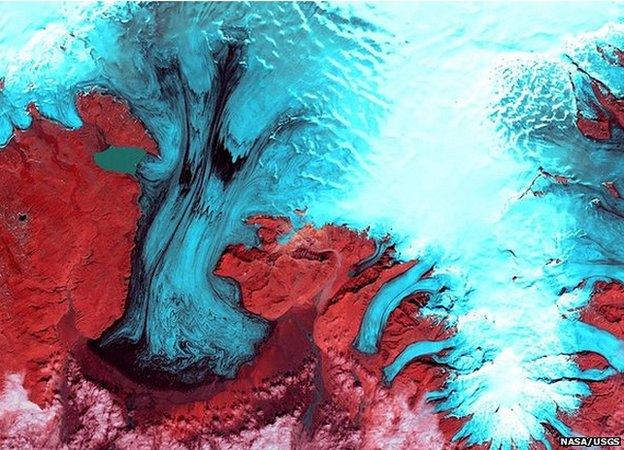

A false colour image of Vatnajokull Glacier in Iceland. The length of the Landsat data record makes it easier to detect real trends in the changing face of Planet Earth. Monitoring the ebb and flow of ice bodies is major use for Landsat data.

Landsat for conservation. It is not possible to see individual birds from space but it is possible to recognise their habitats. The brown staining (centre) on the white ice is a consequence of guano, or penguin poo, dropped by a colony of emperors. This is how the size of penguin populations is estimated.

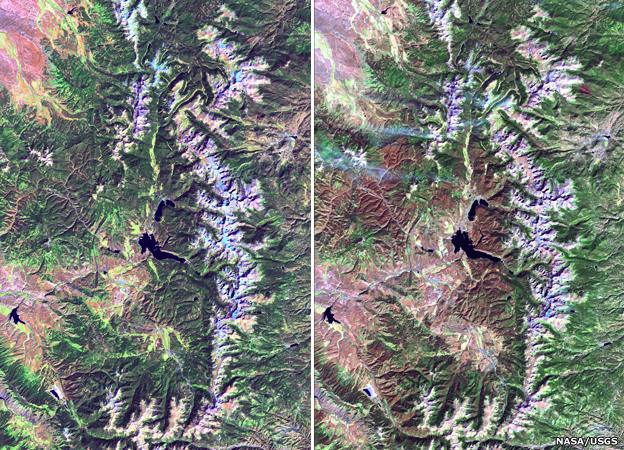

Insect damage: Two views of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado in 2003 (left) and 2010 (right). Spot the areas of tree death caused by the mountain pine beetle. The insect has been spreading its range to the north with obvious associated economic implications.

Water watch: The Aral Sea in central Asia was once the fourth largest lake in the world, but poor irrigation practice severely depleted its water reserves as seen in these Landsat images from 1977, 1989 and 2006. Water resources management is a fundamental use for Landsat data.

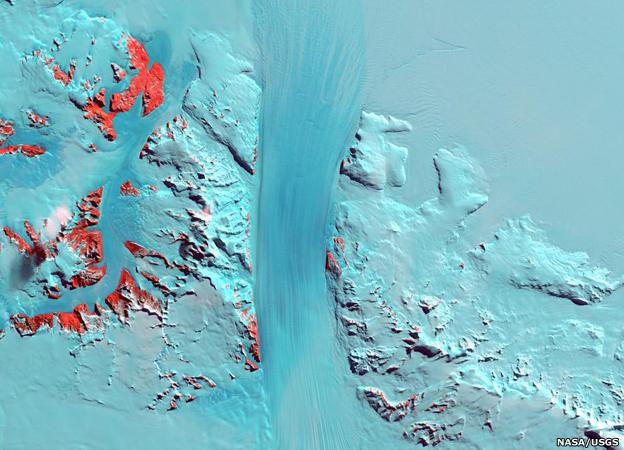

Antarctica's Byrd Glacier: The satellite series has produced some of our best maps of the White Continent. There is now a complete pictorial view thanks to the Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA) project. It is an important baseline from which to judge future change.

Violent Earth: With a 16-day repeat (eight days with two Landsat spacecraft) to every place on the land surface, there is a good chance that a volcanic eruption will be recorded. This picture shows Mount Etna, Italy, blowing its top once again, this time in 2001.

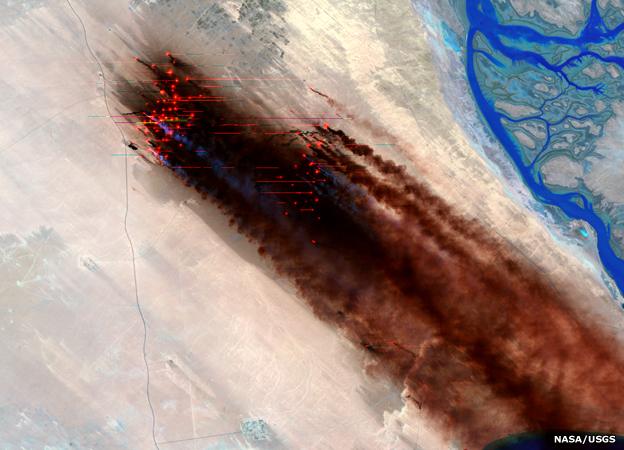

War scene: Landsat saw the devastating environmental fall-out from the end of the Gulf conflict in 1991 when retreating Iraqi forces set fire to Kuwaiti oil wells. The fires raged for months. The entire Landsat archive now has close to 3.5 million images in it.

The meandering Mississippi River in all its glory. The blocks are towns, fields and pastures. Evident in this view are the countless oxbow lakes and cut-offs that trace the length of the North American river. The new Landsat-8 spacecraft should work for at least five years.

Known officially as the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LCDM), external, the new spacecraft is the eighth in the series that is jointly managed by Nasa and the US Geological Survey (USGS), external.

Landsat-8 will operate alongside Landsat-7, which has sufficient fuel to keep working until about 2016.

Both satellites carry an optical imager to take pictures in visible and infrared light, and a thermal infrared sensor to measure the heat radiation coming up off the Earth's surface.

The instruments see details in the range of 15m to 100m across, depending on the particular wavelength of light being measured.

Called officially LCDM for launch, the spacecraft will carry the name of Landsat-8 once in orbit

Landsat-8's instruments are more sensitive, but, critically, directly comparable with 7's.

One key development is the move away from a so-called "whiskbroom" detector design to a "pushbroom" architecture.

In the former, the satellite employs mirrors that sweep back and forth across the field of view, building an image on a relatively small set of detectors.

On Landsat-7, one of these mirrors failed in 2003, leaving gaps in the pictures which then have to be filled with data from a subsequent pass.

The pushbroom technology on Landsat-8 does away with the mirrors and relies instead on a much larger array of detectors.

"We call it pushbroom because it is like pushing a big broom of detectors across the ground track," said Dr Irons.

It will be May before the new spacecraft enters full service. To get to that point, all its systems must go through a strenuous check-out process.

The spacecraft must also be lifted under its own propulsion system into the operational orbit some 705km above the Earth.

As it rises in the sky, it will pass under Landsat-7, giving scientists the opportunity to cross-calibrate their instruments.

The Sentinel-2s will have instruments broadly similar to the Landsat Operational Land Imager

Ultimately, the two spacecraft will be separated such that every point on the Earth's land surface is visited every eight days.

"We have a minimum goal of collecting a cloud-free scene once per season for every land location on the Earth," explained Dr Irons.

"In some places that's just a dry season and a rainy season. But in other places, there's winter, spring, summer and fall."

There is a plan for Europe's forthcoming Sentinel series of satellites to combine with Landsat.

The European Union's Copernicus programme will see the launch of Sentinel-2a and 2b, external in the next three years. Their Multi-Spectral Imagers are broadly similar to the Operational Land Imager on Landsat-8.

"The repeat period for the two Sentinels will be five days, so working with Landsat we would dramatically increase the amount of data available. Our data policies still have to be formally approved but our expectation is that Sentinel data will also be open and free," Dr Josef Aschbacher at the European Space Agency told BBC News.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 January 2013

- Published14 June 2012

.jpg)