Nasa reveals new information about moon probes crash sites

- Published

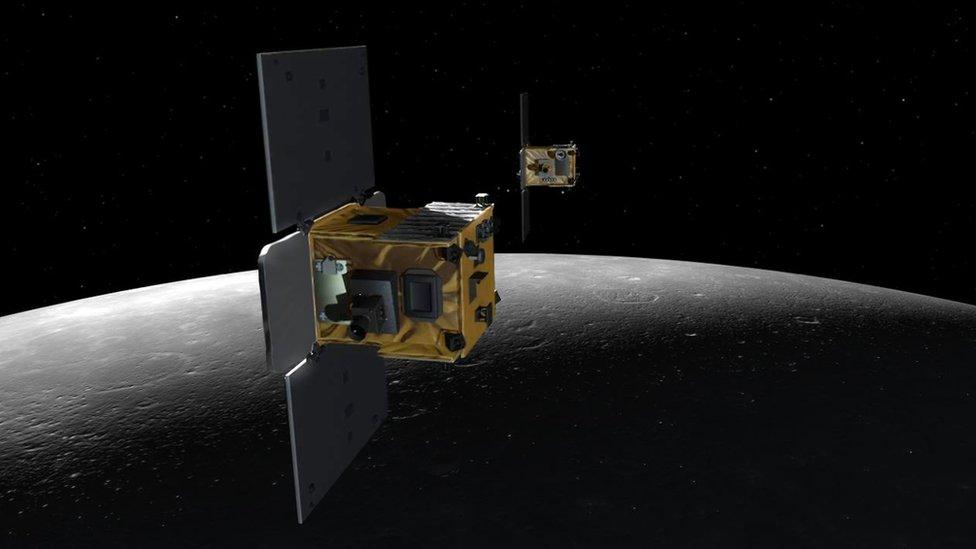

The Grail satellites smashed into the Moon

Nasa has released information about the impacts made when two probes were deliberately crashed into the lunar surface last year.

The Grail gravity mapping satellites were smashed into a mountain near the Moon's north pole in December.

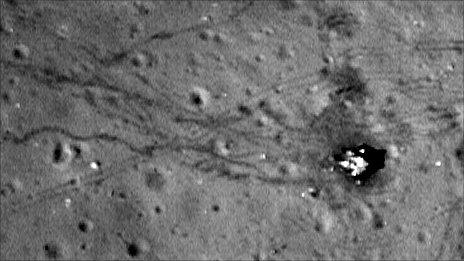

Images taken before and after the crash have now revealed the precise location of the craters created by the craft.

And an analysis of the plumes thrown up by the impact showed mysterious concentrations of mercury.

The two Grail probes, called Ebb and Flow, were each about the size of a washing machine. Launched in September 2011, the spacecraft were designed to map tiny variations in the pull of gravity around the lunar body.

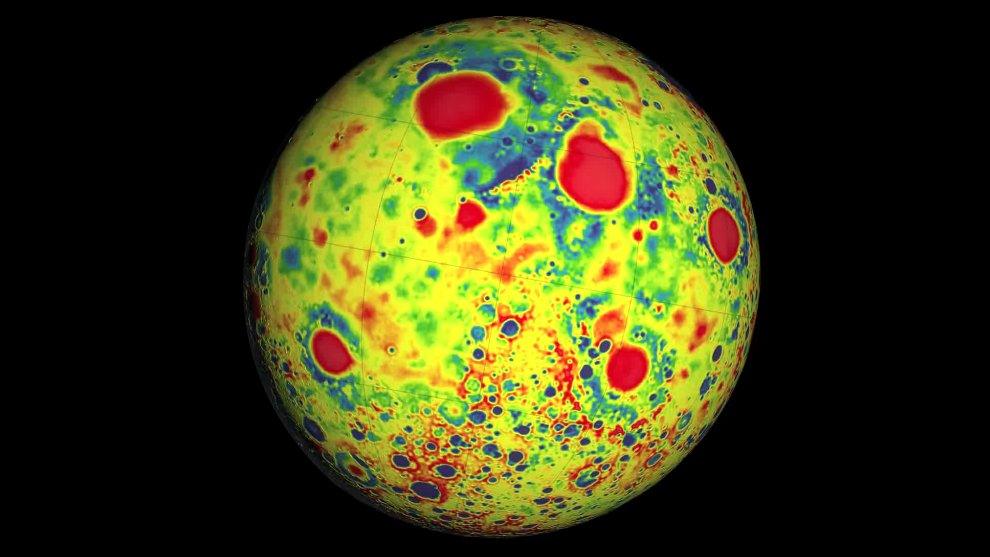

This information should give scientists fresh insight into the internal structure of Earth's satellite.

And it could shed light on remaining mysteries, such as why the crust on the far side of the Moon is thicker than that on the near side.

At the end of the mission, Nasa decided to deliberately ditch the probes to avoid the possibility of an uncontrolled descent on to locations of historic importance, such as the Apollo landing sites.

Mercury mystery

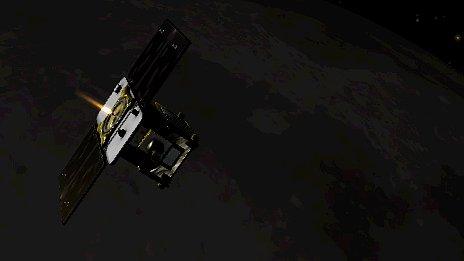

As the pair of probes took their final plunge, Nasa's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, external (LRO) had been manoeuvred into the right place to see the spacecraft slam into an unnamed 2,500m mountain.

Scientists had only three weeks' notice to position LRO to see Grail's fiery finale. By observing the cloud of dust and gas kicked up by each impact, scientists knew they could obtain valuable data about the Moon's composition.

One of LRO's instruments, the Lyman Alpha Mapping Project, external (Lamp), detected enhanced concentrations of mercury and atomic hydrogen in the cloud from the demise of the twin spacecraft.

Mercury is known as a "volatile" - meaning it is easily vaporised - and is thought to be present in cold, permanently shadowed craters on the Moon (and perhaps other bodies). But it was a surprise to find it in an area that receives regular sunlight.

"While our results are still very new, our thinking is that the mercury detected by Lamp from the Grail site might be related to an enhancement at the poles caused by mercury atoms generally hopping across the surface and eventually migrating toward the cold polar regions," said Kurt Retherford, the chief scientist for Lamp.

Scientists think mercury atoms may "hop" across the surface of the Moon towards the poles, causing them to be concentrated in these regions.

It is still unclear whether the hydrogen represents the release of water by the heat of the impact, or whether it simply sheds light on the way that water is formed on the Moon from its chemical constituents.

High-resolution mapping

The two spacecraft were travelling at a velocity of 1.7km per second and came in at very shallow angles of a degree-and-a-half. The impact sites show that the spacecraft kicked up fields of dark debris as they slammed into the lunar soil.

During Grail's three-month primary mission, the spacecraft orbited at an average altitude of 55km. They were then commanded to reduce their height by a factor of two (to 23km) for another three months, allowing them to obtain data at an even better resolution.

For the final science campaign before the planned impacts into the Moon, the twin spacecraft were lowered to an average altitude of 11km, which allowed them to carry out very high-resolution mapping of a lunar impact basin called Orientale. It is one of the youngest and best preserved of such features on the lunar surface.

"We have had very detailed mapping of that basin from images, from orbital spectral data, but we have not had high-resolution of its interior structure," Grail's chief scientist, Prof Maria Zuber, who has been speaking at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, external (LPSC) in The Woodlands, Texas, told BBC News.

The data could shed light on how impacts shaped the evolution of the Moon and other bodies such as the Earth.

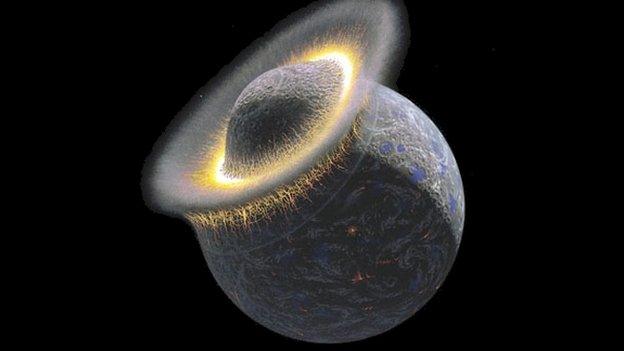

One theory for the difference between the Moon's far side and near side is an ancient collision with a second natural satellite of Earth.

A paper published in Nature journal in 2011, suggested this smaller sibling - if it indeed existed - could have been about one-third the size of the Moon and would have smeared itself across the lunar far side in a low-velocity impact.

"We've been looking at that, but to date we have not seen evidence for that highland area on the Moon being substantially different from surrounding areas," said Prof Zuber.

"So we don't see evidence for another planetary body being pasted on the top.

"But one could imagine that such signatures are extremely subtle. So I am not ready to conclude anything at this point. We and others need to analyse that data in many different ways."

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published17 December 2012

- Published24 July 2012

- Published5 December 2012

- Published18 October 2012

- Published1 January 2012

- Published10 September 2011

- Published6 September 2011

- Published31 March 2011