Kepler telescope spies 'most Earth-like' worlds to date

- Published

- comments

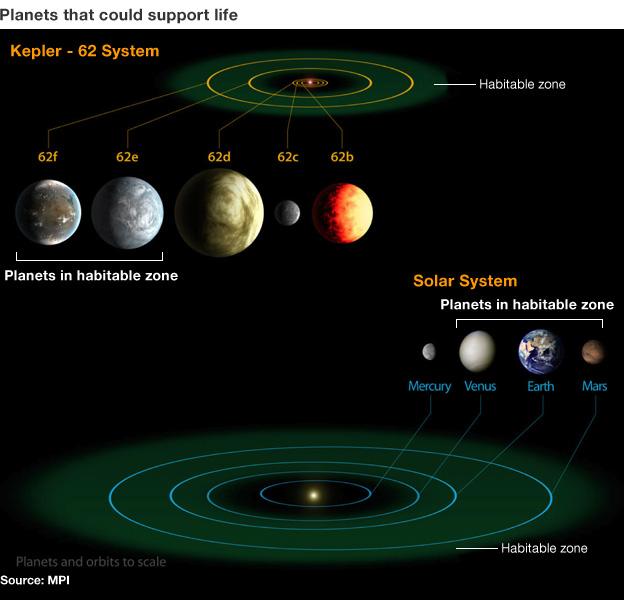

Artist's impression: The outermost pair are the smallest exoplanets yet found in a host star’s habitable zone

The search for a far-off twin of Earth has turned up two of the most intriguing candidates yet.

Scientists say these new worlds are the right size and distance from their parent star, so that you might expect to find liquid water on their surface.

It is impossible to know for sure. Being 1,200 light-years away, they are beyond detailed inspection by current telescope technology.

But researchers tell Science magazine, external, they are an exciting discovery.

"They are the best candidates found to date for habitable planets," stated Bill Borucki, external, who leads the team working on the US space agency Nasa's orbiting Kepler telescope.

The prolific observatory has so far confirmed the existence of more than 100 new worlds beyond our Solar System since its launch in 2009.

The two now being highlighted were actually found in a group of five planets circling a star that is slightly smaller, cooler and older than our own Sun. Called Kepler-62, this star is located in the Constellation Lyra.

The two planets go by the names Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f

Its two outermost worlds go by the names Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f.

They are what one might term "super-Earths" because their dimensions are somewhat larger than our home planet - about one-and-a-half-times the Earth's diameter.

Nonetheless, their size, the researchers say, still suggests that they are either rocky, like Earth, or composed mostly of ice. Certainly, they would appear to be too small to be gaseous worlds, like a Neptune or a Jupiter.

Many assumptions

Planets 62e and 62f also happen to sit a sufficient distance from their host star that they receive a very tolerable amount of energy. They are neither too hot, nor too cold; a region of space around a star sometimes referred to as the "Goldilocks Zone".

Given the right kind of atmosphere, it is therefore reasonable to speculate, says the team, that they might be able to sustain water in a liquid state - a generally accepted precondition for life.

"Statements about a planet's habitability always depend on assumptions," said Lisa Kaltenegger, external, an expert on the likely atmospheres of "exoplanets" and a member of the discovery group.

"Let us assume that the planets Kepler-62e and -62f are indeed rocky, as their radius would indicate. Let us further assume that they have water and their atmospheric composition is similar to that of Earth, dominated by nitrogen, and containing water and carbon dioxide," the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg researcher went on.

"In that case, both planets could have liquid water on their surface: Kepler-62f gets less radiation energy from its host star than the Earth from the Sun and therefore needs more greenhouse gases, for Instance more carbon dioxide, than Earth to remain unfrozen.

"Kepler-62e is closer to its star, and needs an increased cloud cover - sufficient to reflect some of the star's radiation - to allow for liquid water on its surface."

Key signatures

None of this can be confirmed - not with today's technology. But with future telescopes, scientists say it may be possible to see past the blinding glare of the parent star to pick out just the faint light passing through a small world's atmosphere or even reflected off its surface.

This would permit the detection of chemical signatures associated with specific atmospheric gases and perhaps even some surface processes. Researchers have spoken in the past of trying to detect a marker for chlorophyll, the pigment in plants that plays a critical role in photosynthesis.

Dr Suzanne Aigrain, external is a lecturer in astrophysics at the University of Oxford.

She said ground-based experiments and space missions planned in the next few years would give more detailed information on distant planets like those announced by the Kepler team.

Astronomers would like to pin down the masses of the planets (information difficult to acquire with Kepler), as well as getting that data on atmospheric composition.

Dr Aigrain told BBC News: "What we do next is we try to find more systems like these; we try to measure the frequency of these systems; and we try to characterise individual systems and individual planets in more detail.

"That involves measuring their masses and their radii, and if possible getting an idea of what's in their atmospheres. But this is a very challenging task."

Kepler meanwhile will just keep counting planets beyond our Solar System.

It is equipped with the largest camera ever launched into space. It senses the presence of planets by looking for a tiny "shadowing" effect when one of them passes in front of its parent star.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published19 April 2013

- Published15 March 2013

- Published20 February 2013

- Published20 December 2011

- Published23 November 2011

- Published25 December 2012

- Published16 January 2012

- Published9 January 2012