Scientific opinions differ on bee pesticide ban

- Published

.jpg)

Research into the impacts of nenicotinoid chemicals on bees has been inconclusive say some researchers

When the first neonicotinoid insecticide was introduced in 1991, there was a general welcome from scientists because it provided an improved method of tackling some of the world's most destructive crop pests while being safer for humans and the general environment.

Neonicotinoid chemicals are usually applied to seeds, entering every part of a growing plant so all of it becomes poisonous to threats like beetles and aphids. And they are widely used around the world - In the US it's estimated that 94% of corn seed is treated with these chemicals.

Given their prevalence in farming it is little wonder that scientists have sought, external to establish if they have played a role in the decline of bee populations widely seen around the world over the last 10 years.

But the studies carried out to date have not reached a clear conclusion on the impacts of neonicotinoid chemicals. Some, external have shown significant effects. Others have not.

"We're not making this stuff up, we have reason to think this is a problem," Dr Geraldine Wright from Newcastle University told BBC News.

"I think there is an effect of neonicotinoids and I think that based on research I've done in my own lab. Before that I was fairly doubtful, but I do actually think there is an influence."

There are far more research papers that show an effect than don't, says Dr Wright.

However, Dr Julian Little from Bayer in the UK draws a big distinction between studies conducted in the laboratory and those carried out in the field.

"We have never argued about the science, what we have been upset about is how that research has been put into policy. Because when you repeat it with real bees, real colonies in real fields, you don't see any effect."

But Dr Wright says it is wrong to dismiss the research carried out in the laboratory. She says the work is done there precisely because it is possible to control the variables such as the doses of the chemicals the animals are exposed to, and thereby establish cause and effect.

"I think it is incorrect to outright dismiss the work that has been done in the lab on neonicotinoids because it is clearly indicative there is an effect of these pesticides on the bees brain, their behaviour, and I have unpublished data which shows a strong effect on their physiology - the effect we saw we didn't expect and its quite a strong effect."

Dr Wright says that the ban is justified. While the field studies might be unclear, the chemicals do have subtle effects on bees, she says.

"If you feed this stuff to honeybees and you give them a measured dose, they don't just curl up and die, their behaviour changes subtly. They are dependant on their abilities to learn and remember things in order to find food. If the workers can't do that they are not as efficient and that's a problem for the whole colony."

Bayer believe that the a ban on neonicotinoids will not improve the health of bees. Dr Julian Little says that politicians are drawing the wrong conclusions from the research that has been carried out.

"We have two controls for all of this. One is France; we've had massive restrictions on these products for over 10 years, have we seen any improvement in bee health? No.

"The other control is Australia where neonicotinoids are used in exactly the same way as in the UK, same formula same crops and they have the healthiest bees on the planet. The difference there is they don't have varroa."

Varroa is a parasitic mite that has also played a role in the decline of bees over the past decade. They help spread a range of viral infections that are lethal to the animals.

"The varroa mite is key," says Dr Little.

Beekeeping has become very popular in recent years despite the overall decline in bee populations

"If you don't have varroa you have healthy bees regardless of whether neonicotinoids are used. Varroa and bee health are inextricably linked."

Other researchers in the field have concerns over the field data that has been published so far. They are also concerned that focussing too much on the impact of neonicotinoids doesn't fully address the problem. Dr Adam Vanbergen from the UK's Centre for Ecology & Hydrology says he doesn't support the EU ban. Neonicotinoids, he says, are not a smoking gun.

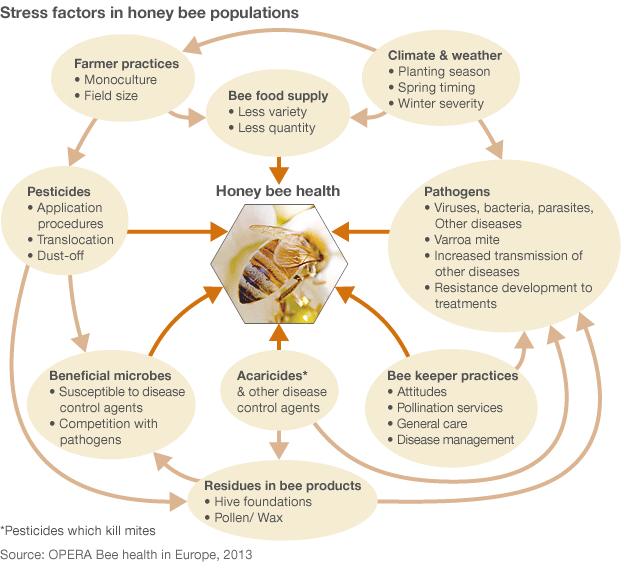

"We are beginning to see some evidence that if our pollinators are not malnourished, they are in a better position to buffer themselves against diseases and indeed pesticide effects. That's the root of it really. Neonicotinoids are part of that, but they are not the whole story.

"If you ban the neonicotinoids, farmers are going to be compelled to use products that are much more harmful to the environment and to a wider range of animals.

"There is a tender balance between protecting the environment and securing the food supply. I still err on the side of not banning, to be honest," he added.

- Published27 March 2013

- Published15 March 2013

- Published31 January 2013

- Published28 September 2010