Tornado Alley: Patterns without predictability

- Published

The National Weather Service was able to issue a tornado warning 16 minutes before the storm struck

The enormous tornado that struck in Moore, Oklahoma, on Monday has added a chilling entry into the list of the deadliest tornadoes on record.

The event has many recalling a record-breaking tornado that struck in precisely the same region, external in 1999, during which the fastest winds ever seen on the Earth's surface were recorded: over 500km/h (310mph).

Tornadoes remain the most viscerally terrifying example of extreme weather, combining an extraordinary capacity for damage with a stubborn unpredictability.

Broadly, they arise in the same conditions that spawn the biggest thunderstorms.

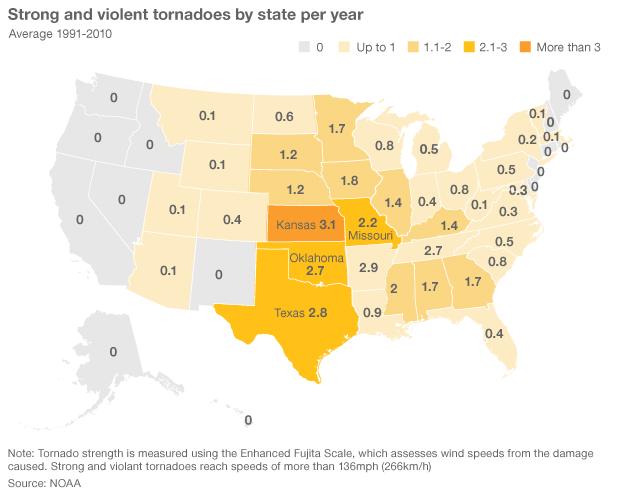

The geography and climatology in the US' interior provide for just this situation with great regularity; three-quarters of the tornadoes that happen on Earth happen in North America. A disproportionate number of those occur in a region in the nation's centre, widely known as "Tornado Alley".

It is a loosely defined area; the state of Texas gets on average the highest annual number of tornadoes, but Kansas, further north, gets the highest number of the more violent storms.

America's Tornado Alley

In simplest terms, warm, wet air blowing in from the Gulf of Mexico meets cold, dry air coming from the massive Rocky Mountain range, hemmed in by air masses on the eastern part of the country. That frequently creates the conditions for grand thunderstorms.

The grandest among them can become what are known as "supercells", below which tornadoes can form, explained Todd Lane of the University of Melbourne in Australia.

"Supercells feature intense upward moving columns of air that rotate, as the wind near the surface is drawn into those columns it begins to rotate and forms the tornado vortex.

"The damage attributed to tornadoes is caused by the strong winds in the vortex and flying debris," he said.

However, it remains unclear what conditions within supercells launch the largest and most violent tornadoes.

The storms' strength is measured on what is known as the Enhanced Fujita scale, which runs from zero to five, with each level representing a greater wind speed. The Moore event was upgraded late on Tuesday to the very top of the scale, an EF5.

A suburb of Oklahoma City, USA has been hit by a deadly tornado. Nick Miller has more about the storm and how tornadoes form.

A tornado's ultimate destructive ability depends on just how large it is, how long it remains in contact with the ground, and of course whether it hits populated areas.

And even that destruction can be seemingly randomly distributed on the ground, said Reed Timmer, an Oklahoma meteorologist and storm chaser.

"Inside that mile, mile-and-a-half circulation you have miniature tornadoes spinning around called suction vortices. That's why you have one house completely devastated with just the bare foundations left standing, whereas the one next door will be less damaged," he told the BBC.

"These suction vortices could have winds that are 300-400mph on small timescales."

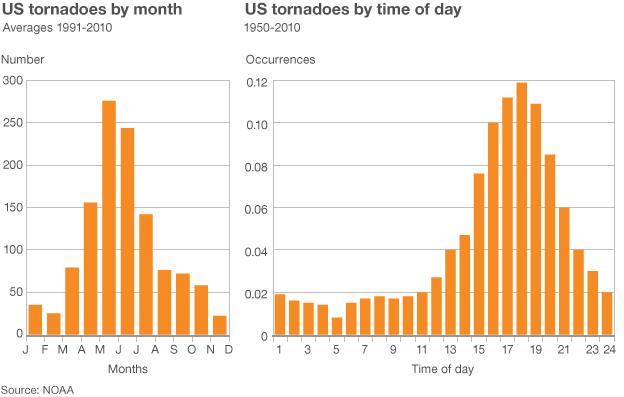

What is evident only in the light of years' worth of data is that there are some patterns in tornado occurrence.

Monday's tornado came during the annual peak of tornado activity in the region; according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), tornado occurrences in the last 30 years strongly peak, external in the months of May and June.

Curiously, they also peak in time of day, tending to occur, external more often in late afternoon hours (Monday's event occurred at a time on the rising edge of this peak, at about 15:00 local time).

There are more tornadoes in total being recorded in recent years, mainly due to better reporting and fewer truly unpopulated areas where they would go unseen.

Yet there is no indication that the frequency of large tornadoes is increasing. While 2011 saw the largest number of storms above EF1, external among records dating back to 1954, 2012 was among the lowest.

And the average number of fatalities caused by tornadoes has been steadily declining since 1925, external - before Monday's storm, only one of the 25 deadliest tornadoes, external occurred in the last 58 years, and most of that list stretches back further than a century.

Much of this can be attributed to better building codes and increasingly advanced warning systems in affected areas - the National Weather Service in Oklahoma issued a warning 16 minutes before the storm hit.

But such warning systems can only give a rough indication of an area in which conditions are almost certain to spark tornadoes; what they cannot provide is a precise prediction of where a tornado will touch down.