Is it possible to kick start science?

- Published

Kickstarter, IndieGogo and other crowd funding sites are increasingly hosting an array of technology projects, with some raising a lot of money, while others have raised debate.

3Doodler claims to be the first 3D printing pen, and raised over $2.3m (£1.5m), having required just $30,000. Currently the Glowing Plants project is creating enthusiasm and controversy with the team's plan of making sustainable natural lighting by using synthetic biology to make plants glow.

There has also been a growth in platforms for crowd funding purely for science research, but there are questions as to whether such a model is feasible for science, and if it does more harm than good.

One of Bisakha Sen's main research interests is a topic in hot discussion: background checks on gun control in the US.

The economist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham has done research on the relationship between background checks on guns and homicide rates. However, due to a lack of funding she has had to put this research aside.

"The biggest source of research funding in the US is the government," says Sen. However, due to strong lobby groups it is hard to receive funding for research into this topic.

Sen had decided to put this work aside until she was contacted by the site Microryza, a platform for crowd funding for scientists. She is now trying to crowd fund her research using the site.

Kick starting science

Microryza found Denny Luan has personally struggled to fund his own scientific research. While a graduate student in biochemistry at the University of Washington, Luan and his classmate Cindy Wu experienced difficulty applying for funding.

Wu required $5,000 to carry out preliminary research for a bigger funding application, but was told she was too junior to apply for money.

The pair felt it shouldn't be so hard to get an idea off the ground, and so looked to crowd funding.

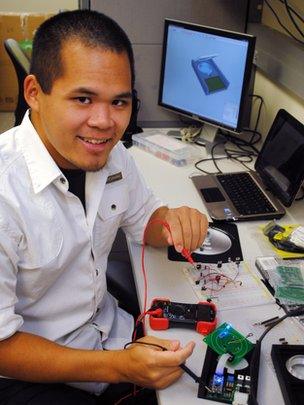

Herbert Sauro's colleague Bennett Kim Ng works on circuits similar to those in their crowd funded project

Microryza joins platforms such as RocketHub and GeekFunder which allow scientists to seek funding from the public.

Luan says that a major hurdle for scientists is that they often need to do preliminary experiments and have some data available before putting in a funding application to the conventional bodies.

However, money is needed to gather this data in the first place.

One of the earliest projects to be fully backed via the site was by University of Washington bioengineer Herbert Sauro, who wanted to make electronic circuits to use when teaching genetics to high school students.

He used the platform to fund preliminary tests on the project, before putting in a more conventional funding proposal to the federal government.

"I think it can kick start bigger projects," he says.

Appealing to the masses

Turning to the public to fund a project also means that scientists have to learn how to communicate with them.

Sauro thinks it's a good idea for graduate students to try crowd funding as they have to learn how to explain what they do to the public, and to engage with them.

Engaging with the public is also a main reason Preston Estep is turning to crowd funding.

Estep is the co-founder of the non-profit Mind First Foundation, as well as the Director of Gerontology at the Personal Genome Project based at Harvard Medical School.

He has launched a campaign on Microryza exploring the genetic roots to mental illness and in particular depression.

Estep is hoping crowd funding will not only raise money for this project but will create a relationship between the scientists and the backers, who can also be involved in the research being carried out.

"We're not just crowd funding but we're also crowd sourcing," he says.

"Science can be done by lots of people and can be done effectively by people who are willing to bring their money, bring their time, and bring their interest," he says.

Dangers and bigger problems

Under current funding models proposals are reviewed by the scientific community. Some believe that there are advantages to this system for both science and the public.

"I wonder about things like oversight and safety," says physicist and science historian David Kaiser of MIT in relation to crowd funding.

Kaiser believes that the current system which takes place within the scientific community ensures that research is rigorous and safe. He warns that there are certain branches of science where the release of data or the use of questionable methodology can have serious consequences for the public, and cites virology as one such field.

"We don't want to have a regulation regime that is just so unwieldy that it strangles innovation," he says, "but we want certain types of oversight, checkpoints and safeguards."

Bisakha Sen is turning to the public to fund her research on gun control

"If crowd sourcing is one more way to almost weaken the regulatory environment then that might actually have unintended consequences."

Science and technology policy researcher Alice Bell of the University of Sussex agrees about the important role the scientific establishment plays in providing oversight and safety.

"These institutions are often built for good reason," she says. For example, the emphasis on peer review is a chance to draw on expertise, and to check that things are being done ethically and rigorously.

Crowd funding removes these checks and balances.

"There is possibly the chance of dodgy research, which could be dangerous in some areas," Bell says.

However, Bell thinks crowd funding can be important for ensuring that scientists are really exploring without constraints from vested interests.

She is sceptical of the increased move in the UK towards matched funding. In this model public funding is given if money has already been raised from other sources first, with these sources often being industry. While Bell is not against working with industry she warns against scientists being pushed to pursue topics in the interests of the status quo.

"That puts a lot of the public research energies on the side of the status quo rather than being able to ask questions that are distant from that," she says.

"Scientific research should be about opening up ideas and new ways of seeing the world."