Viewpoint: Mars - what we've learnt in five years

- Published

On 25 May, it will be five years since Nasa's robotic spacecraft Phoenix touched down in the Martian "arctic". Here, Dr Tom Pike, one of the mission scientists on Phoenix, explains what we've learnt about the Red Planet in that time.

I'm tightly sandwiched between missions to Mars. I'm still analysing data from Phoenix, while building hardware for the seismometers launching on InSight.

In my spare time, I like to keep an eye on the data coming down from Curiosity. Although workdays and weekends are rather blurred, there are some dates I take great care to remember.

Five years ago today, the Phoenix Lander started its descent towards the northern plains of Mars. I was following the live feed from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the Phoenix Science Operations Center in Arizona.

The elation I felt when Phoenix had touched down safely was intense and immediate, but it is only now possible to judge what the mission really achieved.

To make any assessment, I first have to look back from the mission, to see what Phoenix added to our growing knowledge of the Red Planet.

But even a spacecraft that meets all its goals can fade from memory if the next mission outclasses it. The next mission to land on Mars, just last August, was the mighty Mars Science laboratory on board the Curiosity rover, bristling with many more instruments than Phoenix.

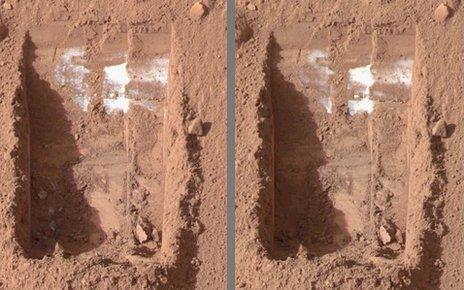

Perhaps the highest profile achievement of Phoenix was to dig down to a buried layer of ice just below the Martian surface. I was the scientist on watch who first recognised that the "white stuff" Phoenix was digging up was slowly disappearing.

This was the definitive proof we'd hit water ice. As later careful examination of fresh meteorite craters showed, this icy layer was not just where Phoenix landed, but stretched right around the most northerly quarter of the planet, external.

But the running joke in the planetary science community was that at least Phoenix could add its name to the list of missions to "discover" water on Mars. It certainly was the first mission to come directly into contact with ice, and melt it. But it had been known for decades that there was water in the form of ice on the planet.

Phoenix uncovered water ice beneath the Martian surface, and saw it vanish

Probably the most important discovery from Phoenix was the presence of perchlorates in the Martian soil, external. These chemical compounds had ironically been detected by adding water brought all the way from Earth. One of the Phoenix instrument suites, MECA, was able to look for key chemical signatures in the resulting muddy soup, and the signature of perchlorate was quite clear.

The issue with perchlorate on Earth is that it is very soluble in water. Finding it in some abundance on the surface of Mars strongly suggested there had not been much liquid water there for quite some time. Any water would have washed the perchlorates away.

Another part of the MECA suite, the two microscopes I was working on, told a similar story. We were able to zoom in to an unprecedented resolution and yet we couldn't find any sign of clays, the signature of liquid water, from the size distribution of the particles in our images.

It took a couple of years to confirm quite how dry Mars must be from all our images, but the conclusion from the chemistry and microscopy of MECA was clear - a major requirement for life on the surface of Mars, liquid water, seems to be missing.

Phoenix was also able to look up into the atmosphere above, and there we saw for the first time snow falling from the Martian sky. Water, water, everywhere, but on Mars all Phoenix saw was ice - certainly nothing to drink.

After five months of mission operations, Phoenix failed as the frigid northern winter set in, with temperatures below -100C and no sunlight. When the Martian orbiters circling the planet were once again able to look down on Phoenix, it was clear the Martian ice had delivered the coup de grace - the solar panels had been snapped off by the weight of the winter's snowfall.

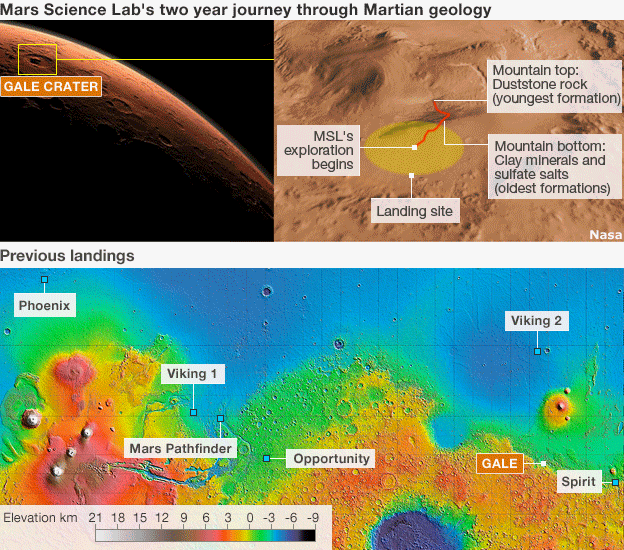

Last August, Curiosity was lowered in some style from its skycrane into Gale Crater, near the Martian equator. The Curiosity rover carries much more instrumental firepower than Phoenix, as might be expected at five times the price tag, and of course it can move around.

Over the last nine months, Curiosity has progressively deployed all its instrumental capacity to analyse the soil it has been rolling over.

But Curiosity has not put Phoenix in the shade, yet. It also sees perchlorates in the soil - they're most likely covering the planet - and as well, the presence of the mineral forsterite also suggests very limited liquid water.

And like the Phoenix microscopes, Curiosity could not find clays in the soil. The soil at the equator looks like it has been just as dry as the soil on the northern plains of Mars.

Phoenix gave the most conclusive picture yet of the inhospitability of the surface of Mars, and Curiosity has produced the same picture from a very different location on the planet. But Curiosity, unlike Phoenix, can roll over to study ancient rock as it traverses Gale Crater, and already it is seeing evidence for a wetter, warmer Mars billions of years old that is captured in the oldest rock formations.

So far, Curiosity has not found any of the organic compounds that would indicate the possibility of life on the planet.

Phoenix gave more than a strong hint that even if there was once life on Mars, it would not now be found near the surface. If Curiosity, or any other mission, does find signs that there was once, long ago, life on Mars, Phoenix will at least deserve a nod for showing where to direct the search.

Dr Tom Pike is a reader in microengineering at Imperial College London. He is working on a forthcoming mission to Mars, called InSight, which is set to launch in 2016.

- Published8 May 2013

- Published4 August 2012

- Published21 August 2012