Gale Crater: Geological 'sweet shop' awaits Mars rover

- Published

- comments

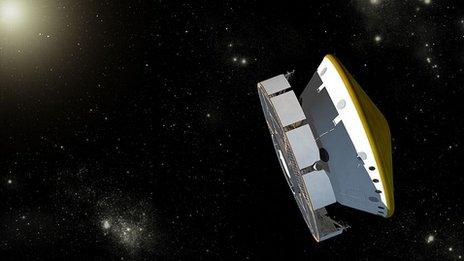

The rover will sample rocks for signs that Mars was once favourable to life

John Grotzinger is the project scientist on Nasa's latest multi-billion-dollar mission to Mars.

He's going to become a familiar face in the coming months as he explains to TV audiences the importance of the discoveries that are made by the most sophisticated spacecraft ever sent to touch the surface of another world.

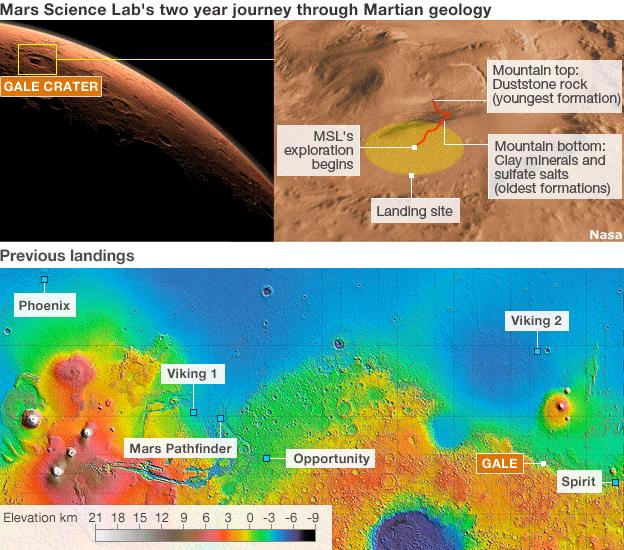

The Curiosity Rover - also called the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), external - is set to land on Monday (GMT) for a minimum two-year exploration of a deep hole on Mars' equator known as Gale Crater.

The depression was punched out by an asteroid or comet billions of years ago.

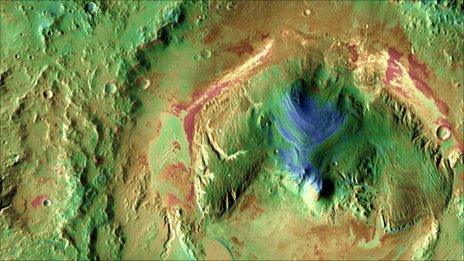

The lure for Grotzinger and his fellow scientists is the huge mound of rock rising 5km from the crater floor.

Mount Sharp, as they refer to it, looks from satellite pictures to be constructed from ancient sediments - some deposited when Mars still had abundant water at its surface.

From orbit, Mount Sharp looks like Australia. Gale is named after an Australian astronomer.

That makes it an exciting place to consider the possibility that those distant times may also once have supported microbial life.

And Curiosity, with its suite of 10 instruments, will test this habitability hypothesis.

Grotzinger is a geologist affiliated to the California Institute of Technology, external and he recently took the BBC Horizon programme to the mountains of the nearby Mojave Desert to illustrate the work the rover will be doing on Mars.

He climbed to a level and then pointed to the rock sediments on the far side of the valley.

"What you see here is a stack of layers that tell us about the early environmental history of Earth, representing hundreds of millions of years," he told Horizon.

"They read like a book of Earth history and they tell us about different chapters in the evolution of early environments, and life.

"And the cool thing about going to Mount Sharp and Gale Crater is that there we'll have a different book about the early environmental history of Mars.

"It will tell us something equally interesting, and we just don't know what it is yet," he said.

Mission scientist Dawn Sumner describes the capabilities of some of the instruments on Nasa's Curiosity rover

Curiosity dwarfs all previous landing missions undertaken by the Americans.

At 900kg, it's a behemoth. It's nearly a hundred times more massive than the first robot rover Nasa sent to Mars in 1997.

Curiosity will trundle around the foothills of Mount Sharp much like a human field geologist might walk through Mojave's valleys. Except the rover has more than a hammer in its rucksack.

It has hi-res cameras to look for features of interest. If a particular boulder catches the eye, Curiosity can zap it with an infrared laser and examine the resulting surface spark to query the rock's elemental composition.

If that signature intrigues, the rover will use its long arm to swing over a microscope and an X-ray spectrometer to take a closer look.

Still interested? Curiosity can drill into the boulder and deliver a powdered sample to two high-spec analytical boxes inside the rover belly.

These will lay bare the rock's precise make-up, and the conditions under which it formed.

"We're not just scratching and sniffing and taking pictures - we're boring into rock, getting that powder and analysing it in these laboratories," deputy project scientist, Ashwin Vasavada, told the BBC.

"These are really university laboratories that would normally fill up a room but which have been shrunk down - miniaturised - and made safe for the space environment, and then flown on this rover to Mars."

The intention on Monday is to put MSL-Curiosity down on the flat plain of the crater bottom.

The vehicle will then drive up to the base of Mount Sharp.

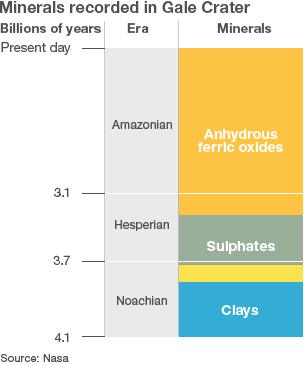

In front of it, the rover should find clay minerals (phyllosilicates) that will give a fresh insight into the wet, early era of the Red Planet known as the Noachian. Clays only form when rock spends a lot of time in contact with water.

Above the clays, a little further up the mountain, the rover should find sulphate salts, which relate to the Hesperian Era - a time when Mars was still wet but beginning to dry out.

"Going to Gale will give us the opportunity to study a key transition in the climate of Mars - from the Noachian to the Hesperian," said Sanjeev Gupta, an Imperial College London scientist on the mission.

"The rocks we believe preserve that with real fidelity, and the volume of data we get from Curiosity will be just extraordinary."

The rover is not a life-detection mission; it does not possess the capability to identify any bugs in the soil or huddled under rocks (not that anyone really expects to find microbes in the cold, dry, and irradiated conditions that persist at the surface of Mars today).

But what Curiosity can do is characterise any organic (carbon-rich) chemistry that may be present.

All life as we know it on Earth trades off a source of complex carbon molecules, such as amino acids - just as it needs water and energy.

Previous missions, notably the Viking landers in the 1970s, have hinted at the presence of organics on Mars. But if Curiosity could make the definitive identification of organics in Gale Crater, it would be a eureka moment and go a long way towards demonstrating that the Red Planet did indeed have habitable environments in its ancient past.

It's a big ask, though. Even in Earth rocks where we know sediments have been laid down in proximity to biology, we still frequently find no organic traces. The evidence doesn't preserve well.

And, of course, there are plenty of non-biological processes that will produce organics, so it wouldn't be an "A equals B" situation even if Curiosity were to make the identification.

Nonetheless, some members of the science team still dream of finding tantalising chemical markers in Gale's rocks.

Dawn Sumner, from the University of California at Davis, is one of them.

"Under very specific circumstances - if life made a lot of organic molecules and they are preserved and they haven't reacted with the rocks in Gale Crater, we may be able to tell that they were created by life. It's a remote possibility, but it's something I at least hope we can find," she said.

"I am confident we will learn amazing new things. Some of them will be answers to questions we already have, but most of what we learn will be surprises to us.

"We've only been on the ground on Mars in six places, and it's a huge planet.

"Gale Crater and Mount Sharp are unlike anything we've been to before. That guarantees we will learn exciting new things from Curiosity."

Horizon: Mission to Mars was broadcast on BBC Two Monday 30 July. Watch online via iPlayer (UK only) or browse more Horizon clips at the above link.

- Published3 August 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published26 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published22 July 2011