Nasa's Curiosity Mars rover reaching turning point

- Published

Immediate target: Point Lake has an appearance reminiscent of Swiss cheese

Nasa is finally thinking about getting its Curiosity rover on the road and heading towards the big mountain at its exploration site in Mars' Gale Crater.

The robot has spent the past six months in a small depression, drilling its rocks and analysing their composition.

But mission managers say they will soon command Curiosity to start moving on the roughly 8km drive to Mount Sharp.

The tall peak is the rover's primary objective, where it expects to learn much about Mars' environmental history.

Engineers plan to begin the drive in the "next few weeks", but they will not rush.

"We are on a mission of exploration. If we come across scientifically interesting areas, we are going to stop and examine them before continuing the journey," explained Curiosity project manager Jim Erickson.

"It's difficult to say exactly how long it will take. I'd hazard a guess that somewhere between 10 months and a year might be a fast pace."

The rover has a few tasks to complete before starting the traverse.

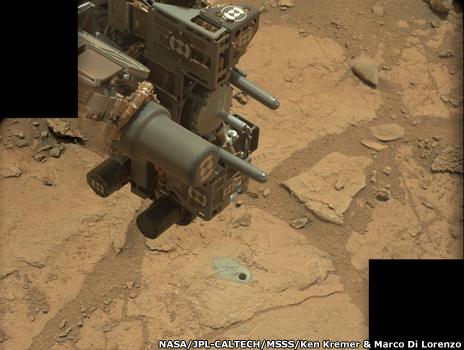

Its onboard laboratories are still examining a powdered sample drilled from the so-called Cumberland rock in the Yellowknife Bay depression.

This analysis should reinforce the findings from an initial sample drilled from a nearby mudstone dubbed John Klein.

This determined the rock had been laid down billions of years ago in a benign water setting, possibly a lake.

The Cumberland drill hole tried to sample a slightly greater concentration of erosion-resistant granules that give the mudstone a slightly bumpy appearance.

But even as the labs do their analysis, Curiosity has started moving towards a rock feature it saw briefly on the way into Yellowknife Bay.

Known as Point Lake, this outcrop has an unusual holey appearance - like Swiss cheese. Scientists are unsure as to whether it is volcanic or sedimentary in character.

"One idea is that it could be a lava flow and those are gas vesicles, and you often see in volcanic rocks on Earth that those kinds of holes are sometimes filled in by secondary minerals. That's one possibility," said Dr Joy Crisp, the deputy project scientist for Curiosity.

"And then it could just possibly be some other kind of massive rock, like a sedimentary rock, that happens not to be layered and either the holes are etched by wind or they're with some mineral that has weathered out; or there were just gases in that rock as it was forming and it's left holes in that rock."

Hard granules give the mudstones a slightly bumpy appearance in places

The mission team also wants to take another look at an outcrop it has called Shaler.

It is a classic example of cross-stratification - a structure produced from thin, inclined layers of sediment.

Again, scientists made brief observations of the outcrop last year. They suspect Shaler's features were sculpted by flowing water, but more detailed investigation will confirm this.

One final task is to survey the ground under Curiosity using its Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (Dan) instrument.

This looks for the presence of hydrogen atoms and can gauge the abundance of water-logged minerals in rocks.

Scientists want to see how the Dan signal changes as the rover moves away from the water-rich clay minerals in the John Klein and Cumberland mudstones to the rocks sitting above Yellowknife Bay.

Once all this work is done, Curiosity will then drive hard to the southwest.

To get to the foothills of Mount Sharp, it will have to skirt a great swathe of sand dunes.

Engineers are using satellite imagery to map a safe route, while researchers are looking for targets of scientific interest where the rover could stop along the way.

The Cumberland drill hole. The mudstones in Yellowknife Bay were probably laid down in an ancient lake

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published3 June 2013

- Published31 May 2013

- Published30 May 2013

- Published25 May 2013

- Published8 April 2013

- Published21 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published27 September 2012

- Published6 August 2012