Carbon from nuclear tests could help fight poachers

- Published

Poaching is now at the highest it has been for two decades, according to conservation groups

The atmospheric carbon left over from nuclear bomb testing could help scientists track poached ivory, new research has found.

These bomb tests changed the level of carbon in the atmosphere, which can be traced to date elephant tusks.

Trafficking poached ivory is increasingly being used to fund civil wars, groups warn.

Scientists say the findings, published in PNAS, external, could make it easier to enforce the ivory ban.

The number of elephants being poached is now at the highest it has been for two decades, according to a UN backed report.

This was highlighted in January when a family of 11 elephants was slaughtered in Kenya, their tusks hacked off with machetes.

Growing demand

In the 1980s, more than half of Africa's elephants are thought to have been wiped out by poachers. This led to an international ban on trading ivory in 1989. As public awareness of the threat of extinction increased, the global demand for ivory dwindled.

But today conservationists believe that a growing demand for ivory in China and other Asian countries is responsible for a huge increase in the number of animals being poached.

Many governments have huge stockpiles of ivory, and it is often unclear when this ivory was acquired and whether or not some of it is leaking into the illegal market.

The bomb-curve

Now scientists have found that radioactive carbon in the atmosphere emitted during the Cold War bomb tests will make it easier to distinguish between illegal ivory to that which was acquired before the trade ban.

The amount of radiocarbon in the atmosphere nearly doubled during nuclear weapons tests from 1952 to 1962, which steadily dropped after tests were restricted to underground. This has been dubbed "the bomb-curve".

The levels have declined since but as they are still absorbed by plant, they enter the food chain and are measurable in plant and animal tissues.

The concentration of radiocarbon found in tiny samples of animal tissue can accurately determine the year of an animals death, from 1955 until today, explained lead author Kevin Uno from Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, US.

"This is different to the traditional dating technique which takes advantage of the loss of radiocarbon through time."

Rhinos are increasingly being targeted as countries like China and Vietnam believe powdered rhino horn has medicinal powers. One preventative tactic is dehorning rhinos safely

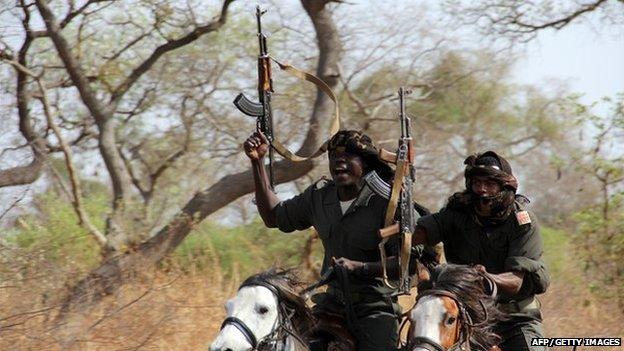

An Asian appetite for ivory is believed to have fuelled poaching in recent years and highly organised crime groups increasingly put the lives of park rangers at risk

Zakouma National Park in Chad has hired a military unit to protect its Elephants, 90% of which have been poached in the last decade

Conservationists warn that unless the demand is curtailed, poaching is edging the African elephant ever closer to extinction

Traditional radiocarbon dating would only be able to pick up an "imperceptible amount of decay" added Dr Uno, but because the bomb spike doubled the concentration or carbon, they were able to find huge variations over the last 60 years, which enabled accurate dating.

Dr Uno said this technique "would dovetail very nicely with DNA testing which tells you the region of origin, but not the date".

As anti-poaching funding is extremely limited, understanding where the poaching hotspots are, as well as how old the tusks are, could help the international community to direct funding to the places most at risk, he added.

"The year an elephant died plays a big role in whether or not the trade [of ivory] is legal. Poached ivory makes it to market relatively quickly, so by measuring the age of a tusk we can say what year it's from. This will help us pinpoint the source of the ivory and how it's getting to market."

Big government organisations like the UN and Interpol have also recently increased efforts looking into the problem.

"Saving elephants - majestic and wonderful species - is priceless. These wildlife forensics are ready to roll, now we need to speak to the organisations who can set up a programme to make it happen."

Organised criminal gangs

Poaching is a problem closely linked to poverty, politics and conflict. Poachers include poor opportunistic individuals and increasingly heavily armed militia groups who use ivory to fund conflicts.

WWF's regional East Africa manager Drew McVey welcomed the new research, and said any help in securing convictions could reduce ivory trafficking.

"The key thing to note is that ivory has been smuggled so far and wide, we've got to cut down the loopholes as much as we can. Though the amount of seizures [of illegal ivory] is increasing each year, we don't know how much we're catching, it's realistic to think we're not catching all the big ones."

He added that poaching is not easy to prevent as "one thing Africa isn't short of is poor people" which is why it's important to cut down the ways people are moving ivory around.

"Rather than targeting people on the ground, we need to reduce the demand from middle men and the consumers," Mr McVey told BBC News.

.jpg)

The researchers analysed tusk samples smaller than a pinch of salt

As for the scientific process involved, Paula Raimer from Queen's University Belfast, said the study removes doubt that the C14 emitted from bombs can be used to date ivory.

"The work is of particular importance for forensics use in endangered species because the authors show that C14 can be used to determine the age of death or collection of ivory as well as establishing growth rates, so that other data from the teeth can also be put on a calendar time scale."

The study has wider implications for crime forensics, she added, as bomb carbon could be used to date human bones as well as to detect art forgeries.

- Published26 April 2013

- Published15 January 2013

- Published10 January 2013

- Published8 January 2013