Rust promises hydrogen power boost

- Published

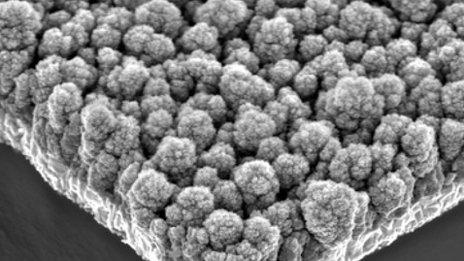

The cauliflower-like nanoparticles are grown as a layer on an electrode

Rust could help boost the efficiency of hydrogen production from sunlight - a potentially green source of energy.

Tiny (nano-sized) particles of haematite (crystalline iron oxide, or rust) have been shown to split water into hydrogen and oxygen in the presence of solar energy.

The result could bring the goal of generating cheap hydrogen from sunlight and water a step closer to reality.

Details are published in the journal Nature Materials.

Researchers from Switzerland, the US and Israel identified what they termed "champion nanoparticles" of haematite, which are a few billionths of a metre in size.

Bubbles of hydrogen gas appear spontaneously when the tiny grains of haematite are put into water under sunlight as part of a photoelectrochemical cell (PEC).

The nanostructures look like minuscule cauliflowers, and they are grown as a layer on top of an electrode.

The key to the improvement lies in understanding how electrons inside the haematite crystals interact with the edges of grains within these "champions"

Where the particle is correctly oriented and contains no grain boundaries, electrons pass along efficiently.

This allows water splitting to take place that leads to the capture of about 15% of the energy in the incident sunlight - that which falls on a set area for a set length of time. This energy can then be stored in the form of hydrogen.

Identifying the champion nanoparticles allowed Scott Warren and Michael Graetzel from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, to master the methods for increasing the effectiveness of their prototype cell.

Iron oxide is cheap, and the electrodes used to create abundant, environmentally-friendly hydrogen from water in this photochemical method should be inexpensive and relatively efficient.

The hydrogen made from water and sunlight in this way could then be stored, transported, and sold on for subsequent energy needs in fuel cells or simply by burning.

Commenting on the research, Dr Chin Kin Ong, from the department of chemical engineering at Imperial College London told BBC News the research could yield material that was "cheap, earth-abundant and efficient at photon-to-electron-to hydrogen energy conversion".

- Published28 February 2013

- Published20 September 2011

- Published15 August 2011