World's first lab-grown burger is eaten in London

- Published

- comments

Food critics give their verdict on the burger's taste and texture

The world's first lab-grown burger has been cooked and eaten at a news conference in London.

Scientists took cells from a cow and, at an institute in the Netherlands, turned them into strips of muscle that they combined to make a patty.

One food expert said it was "close to meat, but not that juicy" and another said it tasted like a real burger.

Researchers say the technology could be a sustainable way of meeting what they say is a growing demand for meat.

The burger was cooked by chef Richard McGeown, from Cornwall, and tasted by food critics Hanni Ruetzler and Josh Schonwald.

Upon tasting the burger, Austrian food researcher Ms Ruetzler said: "I was expecting the texture to be more soft... there is quite some intense taste; it's close to meat, but it's not that juicy. The consistency is perfect, but I miss salt and pepper.

"This is meat to me. It's not falling apart."

Food writer Mr Schonwald said: "The mouthfeel is like meat. I miss the fat, there's a leanness to it, but the general bite feels like a hamburger.

"What was consistently different was flavour."

Prof Mark Post, of Maastricht University, the scientist behind the burger, remarked: "It's a very good start."

The professor said the meat was made up of tens of billions of lab-grown cells. Asked when lab-grown burgers would reach the market, he said: "I think it will take a while. This is just to show we can do it."

Sergey Brin, co-founder of Google, has been revealed as the project's mystery backer. He funded the £215,000 ($330,000) research.

Prof Tara Garnett, head of the Food Policy Research Network at Oxford University, said decision-makers needed to look beyond technological solutions.

"We have a situation where 1.4 billion people in the world are overweight and obese, and at the same time one billion people worldwide go to bed hungry," she said.

Professor Mark Post of Maastricht University explains how he and his colleagues made the world's first lab-grown burger

"That's just weird and unacceptable. The solutions don't just lie with producing more food but changing the systems of supply and access and affordability, so not just more food but better food gets to the people who need it."

Stem cells are the body's "master cells", the templates from which specialised tissue such as nerve or skin cells develop.

Most institutes working in this area are trying to grow human tissue for transplantation to replace worn-out or diseased muscle, nerve cells or cartilage.

Mr Schonwald said he missed the fat, but that the "general bite" was authentic

Prof Post is using similar techniques to grow muscle and fat for food.

He starts with stem cells extracted from cow muscle tissue. In the laboratory, these are cultured with nutrients and growth-promoting chemicals to help them develop and multiply. Three weeks later, there are more than a million stem cells, which are put into smaller dishes where they coalesce into small strips of muscle about a centimetre long and a few millimetres thick.

These strips are collected into small pellets, which are frozen. When there are enough, they are defrosted and compacted into a patty just before being cooked.

Because the meat is initially white in colour, Helen Breewood - who works with Prof Post - is trying to make the lab-grown muscle look red by adding the naturally-occurring compound myoglobin.

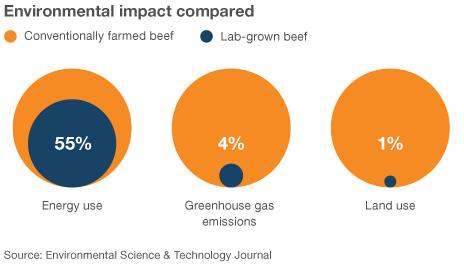

An independent study found that lab-grown beef uses 45% less energy than the average global representative figure for farming cattle. It also produces 96% fewer greenhouse gas emissions and requires 99% less land.

"If it doesn't look like normal meat, if it doesn't taste like normal meat, it's not... going to be a viable replacement," she said.

She added: "A lot of people consider lab-grown meat repulsive at first. But if they consider what goes into producing normal meat in a slaughterhouse, I think they would also find that repulsive."

The BBC's Pallab Ghosh reports from Duggie's Dogs hot dog restaurant in Downtown Vancouver

Currently, this is a work in progress. The burger revealed on Monday was coloured red with beetroot juice. The researchers have also added breadcrumbs, caramel and saffron, which were intended to add to the taste, although Ms Ruetzler said she could not taste these.

At the moment, scientists can only make small pieces of meat; larger ones would require artificial circulatory systems to distribute nutrients and oxygen.

In a statement, animal welfare campaigners People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta) said: "[Lab-grown meat] will spell the end of lorries full of cows and chickens, abattoirs and factory farming. It will reduce carbon emissions, conserve water and make the food supply safer."

Critics of the technology say that eating less meat would be an easier way to tackle predicted food shortages.

The latest United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization report on the future of agriculture, external indicates that most of the predicted growth in demand for meat from China and Brazil has already happened and many Indians are wedded to their largely vegetarian diets for cultural and culinary reasons.

- Published19 February 2012

- Published23 February 2012

- Published30 July 2012