Mars rover celebrates a year of discovery

- Published

- comments

The reaction from the Nasa control room as the robot landed

It's exactly a year since that nerve-shredding descent of the Curiosity rover to the surface of Mars.

Who can forget the agonising "seven minutes of terror" as the Nasa robot entered the planet's atmosphere and hurtled towards the ground?

The engineers who designed the vehicle's landing mechanism said they had every confidence it would work, but they also conceded their hovering "skycrane" looked a little "crazy".

We needn't have worried; everything worked like a dream. So well in fact that the robot came to rest about 1.5km (one mile) from where navigators had put their notional bull's-eye - and that after a journey of 570 million km (355 million miles) from Earth. Truly impressive.

So, 12 months on, what has Curiosity told us about Mars?

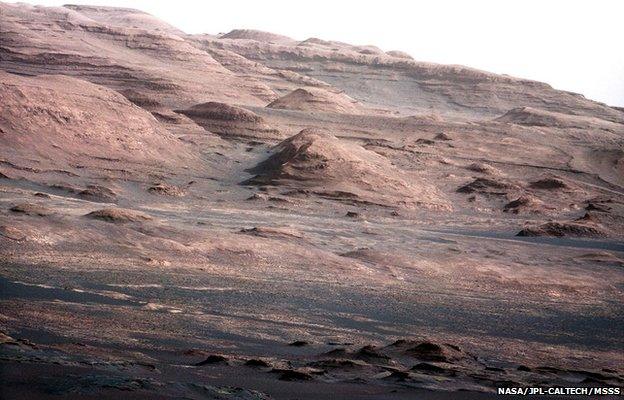

The rover landed on the floor of the 155km (95 miles) wide Gale Crater, close to a tall mound of rock referred to as Mount Sharp.

According to satellite imagery, this 5km (three miles) high peak has sediment layers at its base that look as though they were deposited in, or substantially altered by, water - a perfect place, everyone expected, to look for signs that Mars might once have had environments capable of supporting microbial life.

The first year of operations has seen Curiosity firmly establish the planet's past habitability potential - but not at Mount Sharp.

Such have been the geological treasures out on the crater floor that the rover has been able to fulfil its main mission objectives before even reaching its primary destination.

Just in the act of landing, Curiosity was able to uncover remarkable information about Mars' ancient history.

Dust blown away by its descent engines revealed conglomerates - rocks made up of small pebbles cemented together by finer material.

When the vehicle's survey instruments got a close-up look at these stone jumbles, they were able to confirm that the pebbles were just the sort of gravels you'd find in rivers on Earth.

Scientists' calculations indicated the pebbles' edges had been rounded in waters that flowed to depths that were very likely waist-deep at times.

Gale's conglomerates: The kind of thing you would find on Earth

And there was more. Analysis of mudstones drilled just half a kilometre from the landing site pointed to the presence, billions of years ago, of a lake where neutral waters would have collected for extended periods. In fact, the more Curiosity looked, the clearer the evidence became for a wetter past at Gale, with the Shaler outcrop being my personal favourite.

This pile of thin, inclined layers of sediment is a classic sign of cross-stratification - a rock feature sculpted by water moving in a turbulent flow. It's something routinely observed by geologists on Earth.

"I think what Gale has shown us so far is that Mars is truly a good place to explore," says Prof Sanjeev Gupta, a Curiosity mission scientist from Imperial College London, UK.

"We've seen this diverse pattern of ancient environments, a tremendous richness - lakes lapping up on shorelines and rivers sloshing into these lakes.

"And it's not just surface water flow, either; we've seen sub-surface flow as well - water moving through the rocks.

"So, while the rocks are static, as geologists we see this dynamic picture of the landscape, and it's been really exciting."

Shaler records the action of a turbulent flow of water

Of course, the fact that water may have been plentiful in Mars' distant past is not the same as saying the planet also hosted life. It's just a prerequisite, certainly as we understand it on Earth.

Other "must haves" include a source of energy to drive the metabolism of organisms, and a source of carbon to build their cellular structures.

All life on Earth trades off a source of organic molecules, such as amino acids. Curiosity has yet to see this availability signal at Gale, but that is not really surprising.

Even in Earth rocks where we know sediments have been laid down in proximity to biology, we still frequently find no organic traces. The evidence doesn't preserve well and in the particularly harsh surroundings of modern-day Mars, this is likely to be doubly so.

And then, of course, there are plenty of non-biological processes that can produce organics, so it wouldn't be an "A equals B" situation even if Curiosity were to make such an identification.

Nonetheless, there is hope that the rover can turn up some interesting organic chemistry at Mt Sharp.

But it's going to take a while to get to the mountain. The preferred investigation site is some 8km (five miles) distant - a long way for a robot that moves at most about 100m a day.

The wait, however, will certainly be worth it. The tall succession of rocks should open the book on the geological evolution of Mars. In the many layers at the base of the mountain, researchers hope to see the record of different water events come and go, through perhaps hundreds of millions of years. And the pictures - they'll blow your mind, says Prof Dawn Sumner, a mission scientist from the University of California at Davis, US.

The long sequence of rocks at Mt Sharp will help fill out the story of the geological evolution of the planet

"It's going to be like walking through a national park, like the Canyonlands, external of the US or the Bungle Bungle, external in Australia; it's just completely different from anywhere we've been on Mars so far.

"Even just looking at the images we have taken from kilometres away, you can see that it just looks amazing.

"The slopes on the sides of those hills are so steep they count as cliffs, and there'll be layers in them that will probably be different colours and textures."

The best is yet to come.