Peat bogs and fenlands 'hugely important' in conflicts

- Published

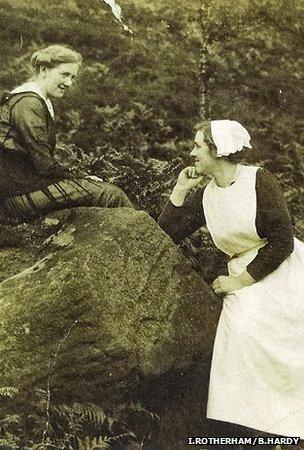

The harvesting and processing of sphagnum moss was carried out on an industrial scale during World Wars One and Two

The UK's peat bogs and fenlands played a major role during times of conflict but they have been often overlooked or forgotten, a conference will be told.

Delegates to a three-day gathering in Sheffield will hear how sphagnum moss was harvested from UK wetlands for wound dressings during World War One.

Other war-time uses included using peat as bedding for the army's horses and as an alternative fuel source.

The conference will also look at how the habitats helped defending forces.

"Throughout history, [wetlands] have been hugely important in many of the conflicts," explained conference organiser Ian Rotherham, professor of environmental geography at Sheffield Hallam University.

Forgotten fens

While woodlands and arable land were widely associated with being part of national war efforts, wetlands - such as peat bogs and fens - were often overlooked, he added.

Yet they provided a variety of resources that were often found on the frontline in times of conflict.

For example, Prof Rotherham said, sphagnum moss - tiny plants that grow tightly together to form carpets across bogs - was harvested and processed to provide wound dressings.

"Although there is evidence that the potential medical applications of sphagnum was known to prehistoric people, its use was rediscovered in the 1800s," he observed.

He recalled how a German soldier had been injured.

"It took a week to take him to the nearest available medical facility, so they packed the wound with sphagnum and when they had taken the dressing off, the wound had healed," he told BBC News.

Doctors during this pre-antibiotic time were surprised, as a severe wound generally meant the loss of a limb or death.

"So - as a result - what happened, particularly in World War One but also in World War Two, was that the call went out for people to collect this sphagnum moss to aid the war effort."

As part of his research, Prof Rotherham said: "I have had people contact me who were children at the time, saying they went out during their lunch breaks to collect sphagnum moss off the moors and bogs on the Pennines.

"Bogs at that time were much more widespread as the landscape was wetter because many peat bogs had not been drained or destroyed.

"But when the stuff came back, it was processed industrially. I have photographs of factories in North America with rank upon rank of shelves, where they have got people sorting the stuff, drying the stuff, packing into muslin bags.

"When I first started looking at this, you thought that it was just a few people going out and grabbing a handful of the stuff and binding it on to a wound. But it is not, it is a really complicated process."

Horse litter

As well as harvesting the moss, the peat and soil itself was also a prized asset - as horse litter.

All classes and all ages were involved in war efforts in England

"You had a landscape that was powered by people and powered by horses," Prof Rotherham explained.

"If you have got horses in towns and cities , then you needed horse litter - and the horse litter was peat. There was a huge industry of harvesting peat - not for fuel or horticulture - but for horses."

He added that horse-power was "hugely important to the war effort" during World War One.

"They needed litter and that was harvested peat, so it was taken from the bogs and sent over.

"All of this has been completely forgotten. So, as ecologists looking at the landscape, we need to understand how we have got to where we are today."

Another use of peat was as a fuel, a use that - on an industrial scale at least - had been superseded by the ability to mine coal efficiently.

"We were quite interested in that from an academic point of view as far as what was happening in the landscape because in a time of conflict, you suddenly don't have enough energy. So where do you go? You go back to use sources you used in the past," Prof Rotherham said.

He explained that he found numerous US government reports looking at how to tackle a wartime fuel crisis. "They were looking at peat - how to harvest it, how to process it, what reserves there were. It was like an early 20th Century version of fracking."

He added that European nations caught up in the middle of the conflict, such as France and Germany, also returned to cutting peat bogs again.

Home advantage

As well being a vital source of resources, wetlands also played a strategically important role as battlefields.

Prof Rotherham explained that a 600-page report in the US Library of Congress, written in 1921, provided a strategic analysis of the battlefields of World War One.

He said the author identified "how strategically important the marshes and the peat bogs were".

"That was because they had a huge effect on what you can do in terms of moving men and machinery."

He added that there were examples that stretched further back into the past, such as the Franco-German War in the second half of the 19th Century.

"French generals, knowing the terrain, lured a vastly superior German force into an area of quagmire and then basically annihilated them because they knew the landscape but the Germans did not, who went into the area and were overwhelmed."

Prof Rotherham hopes the three-day event will raise the profile of wetlands' role in conflicts ahead the centenary of World War One.

"There are almost no remaining first-hand memories, so we are trying to capture any recollections people have got - otherwise they will disappear," he said.

The conference, running from 4-6 September, has been organised by Sheffield Hallam University, South Yorkshire Biodiversity Research Group, Biodiversity and Landscape History Research Institute, British Ecological Society and the International Peat Society.

- Published17 May 2012

- Published23 February 2012