World's oldest bog body hints at violent past

- Published

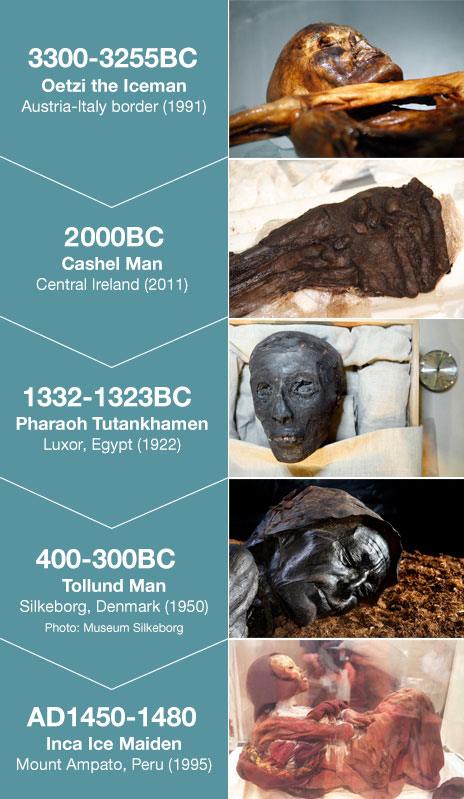

A CT scan of Cashel Man showing the compressed state of the remains that are 500 years older than Tutankhamen

Cashel Man has had the weight of the world on his shoulders, quite literally, for 4,000 years.

Compressed by the peat that has preserved his remains, he looks like a squashed, dark leather holdall.

Apart, that is, from one forlorn arm that stretches out and upward and tells us something of the deliberate and extremely violent death that he suffered 500 years before Tutankhamen was born.

Cashel Man is now being studied at the National Museum of Ireland's research base in Collins Barracks, Dublin. He was discovered in 2011 by a bog worker in Cashel bog in County Laois.

When the remains are brought out of the freezer, it is hard to tell that this was ever a human being.

"It does look like mangled peat at first," says researcher Carol Smith.

"But then you can see the pores on the skin and it takes on a very human aspect quite quickly."

Carol starts to spray the body with non-ionised water. This prevents it deteriorating when exposed to room temperatures.

As we peer at the glistening bog-tanned body, we can see small, dark hairs on the skin, and a trail of vertebrae along his back.

Experts say that the remains of Cashel Man are extremely well preserved for his age. Radiocarbon dating suggests that he is the earliest bog body with intact skin known anywhere in the world. He is from the early Bronze Age in Ireland about 4,000 years ago.

Bog bodies with internal organs preserved have cropped up in many countries including Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Scotland and Spain.

But in Ireland, with its flat central, peaty plain, they have been particularly plentiful.

In the past 10 years, there have been two other significant finds, in varying states of decay. Both Clonycavan Man and Old Croghan Man, who were discovered in 2003, external, were violently killed but the preservative powers of the bog have allowed science to piece together their stories.

"The bog is an amazing place," says Isabella Mulhall, who co-ordinates the bog bodies research project at the museum.

"It is basically an anaerobic environment and the oxygen that bacteria feed off is not present, and therefore decomposition does not occur."

The process of preservation though is complicated, involving several factors including Sphagnum moss, which helps extract calcium from the bones of buried bodies.

Another critical element is acidity.

"The pH levels vary in bogs and in some cases you may not get the bog mummy; you may get a bog skeleton," says Isabella Mulhall.

"Even within a site, you may have a body partially mummified and the lower half could be skeletonised."

While the preservation offered by the bog gives scientists huge amounts on information on the diet, living conditions, background and lifestyle of the bodies, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

The bog destroys the DNA, depriving researchers of genetic information and making it very difficult for Irish people to claim descent from these ancients.

Researchers have to keep the remains of Cashel Man moist to prevent deterioration at room temperature

The Iron Age bodies of Clonycavan Man and Old Croghan Man are on display at the museum, which sits in a wing of Leinster House, the Irish parliament.

Eamonn Kelly is the long-time Keeper of Irish Antiquities and a man who has worked on all the major bog body finds.

He is an archaeologist of the old school, with a deep knowledge of Irish and European mythology and symbolism.

He patiently explains the stories behind the bodies on display, where the well-preserved hands are a striking feature.

"They are so evocative really. You can see those arms cradling a baby, or caressing a lover, or wielding a sword. But the personality is there; it's been preserved in their remains," he says.

Eamonn, or Ned as he is universally known, has developed a theory that connects the significant finds made in Ireland.

He argues that the bodies, all male and aged between 25 and 40, suffered violent deaths as victims of human sacrifice.

"When an Irish king is inaugurated, he is inaugurated in a wedding to the goddess of the land.

"It is his role to ensure through his marriage to the goddess that the cattle will be protected from plague and the people will be protected from disease.

The preserved hairs on the skin of Cashel Man seem to be still alive

"If these calamities should occur, the king will be held personally responsible. He will be replaced, he will pay the price, he will be sacrificed."

Nipple evidence

Eamonn says that Cashel Man fits this pattern because his body was found on a border line between territories and within sight of the hill where he would have been crowned. He suffered significant violent injuries to his back, and his arm shows evidence of a cut from a sword or axe.

However, a critical piece of information that would cement this argument is missing.

Because Cashel Man's chest was destroyed by the milling machine that uncovered him, the researchers are unable to examine the state of his nipples.

In the other two bog body cases, says Eamonn Kelly, the nipples had been deliberately damaged.

"We're looking at the bodies of kings who have been decommissioned, who have been sacrificed. As part of that decommissioning, their nipples are mutilated.

"In the Irish tradition they could no longer serve as king if their bodies were mutilated in this way. This is a decommissioning of the king in this life and the next."

The real surprise with Cashel Man is his age, being 1,500 years older than the other significant finds. But he may not be the last.

As the midland bogs are depleted, the scientists believe they could find other bodies of a similar age.

Archaeologist Eamonn Kelly at the site of the discovery of Cashel man in 2011

In December last year, more remains were found in Rossan bog, Co Meath, of a body that's being called Moydrum Man. Isabella Mulhall says there are indications that it could be the same age as Cashel Man.

"He hasn't been dated as yet, but we suspect that he would come as well from the very early levels of the bog and he would fit into that Bronze Age date range as well. But we have to confirm that with carbon dating," she says.

In the future, Cashel Man is likely to join the other bodies in the National Museum. Like the others, he will be treated sympathetically and with some reverence. This is hugely important to Eamonn Kelly and all the staff.

"I see these bodies as ambassadors who have come down to us from a former time with a story to tell. I think if we can tell that story in some small measure we can give a little added meaning to those lives that were cut short.

"And even though it was thousands of years ago, it is still in each and every case a human tragedy."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published24 September 2013

- Published4 September 2013

- Published22 August 2011

- Published4 August 2013