Five key questions about climate facing the IPCC

- Published

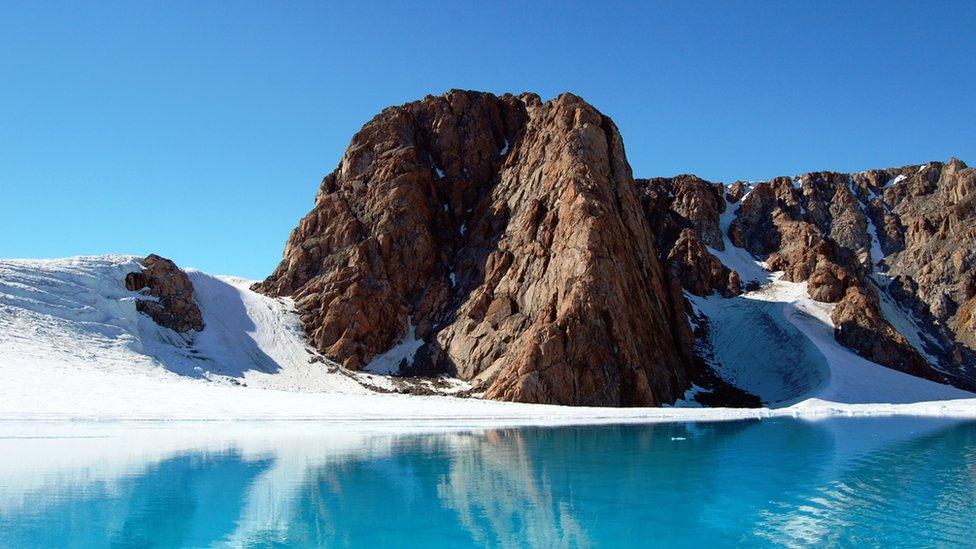

The rapid melting of Arctic ice is one of the key indicators of global warming, according to the IPCC

Our environment correspondent Matt McGrath looks at five critical questions now facing the Nobel prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as it prepares to present its latest report in Stockholm later this week.

The IPCC - weren't they the ones who said the Himalayan glaciers would disappear by 2035? How can we trust what they say this time?

The weight given to the reports of the IPCC is a measure of the global scale of scientific involvement with the panel.

Divided into three working groups, external that look at the physical science, the impacts and options to limit climate change, the panel involves thousands of scientists around the world.

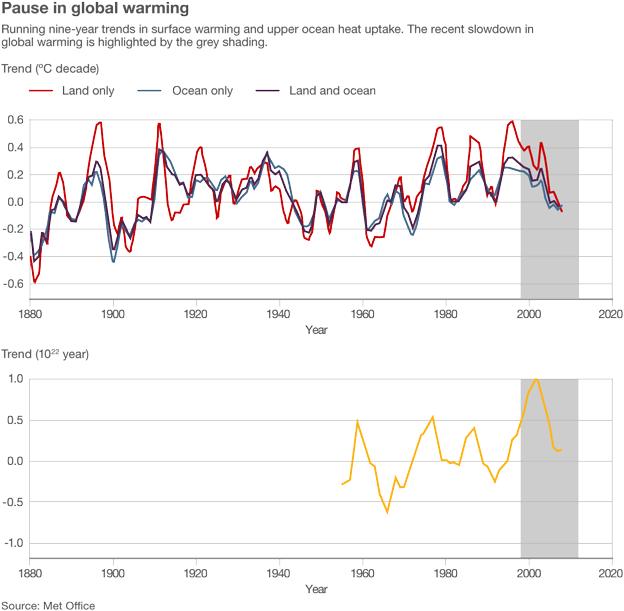

How temperatures have risen since 1884

The first report, to be presented in Stockholm, has 209 lead authors and 50 review editors from 39 countries.

The 30-page Summary for Policymakers that will be published after review by government officials in the Swedish capital is based on around 9,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers and 50,000 comments from the expert reviewers.

But among these icebergs of data, things can and do go awry.

In the last report, published in 2007, external, there were a handful of well publicised errors, including the claim that Himalayan glaciers would disappear by 2035. The wrong percentage was also given for the amount of land in the Netherlands under sea level.

The IPCC admitted it had got it wrong, external and explained that, in a report running to 3,000 pages, there were bound to be some mistakes. The Himalayan claim came from the inclusion of an interview that had been published in the magazine New Scientist.

In 2009, a review of the way the IPCC assesses information, external suggested the panel should be very clear in future about the sources of the information it uses.

The panel was also scarred by association with the "Climategate" rumpus, external. Leaked emails between scientists working for the IPCC were stolen and published in 2009.

They purported to show some collusion between researchers to make climate data fit the theory of human-induced global warming more clearly. However at least three investigations found no evidence to support this conclusion.

But the overall effect of these events on the panel has been to make them more cautious.

Although this new report is likely to stress a greater certainty among scientists that human activities are causing climate warming, in terms of the scale, level and impacts, the word "uncertainty" features heavily.

"What we are seeing now is that this working group is getting more careful than they already were," said Prof Arthur Petersen, chief scientist at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

"Overall, the message is, in that sense, more conservative I expect, for this IPCC report compared to previous ones."

Hasn't global warming stopped since 1998?

The 2007 IPCC report made no mention of any slowdown or standstill in temperature rises in recent decades. They pointed out that the linear warming trend over the previous 50 years was 0.13C per decade, which was twice that for the past 100 years.

They forecast that, if emissions of carbon dioxide continued on their existing path, over the next century the climate would respond by warming between 2C and 4.5C, with a most likely rise of 3C.

But since 2007, climate sceptics have loudly argued that global average temperatures haven't actually gone above the level recorded in 1998.

The issue is now being taken more seriously by the IPCC and other respected science organisations.

My colleague David Shukman summarised some of the explanations now being offered as to why the temperatures have not risen more quickly in line with the modelling.

Most scientists believe that the warming has continued over the past 15 years, but more of the heat has gone into the oceans. They are unsure about the mechanisms driving this change in behaviour.

The most recent peer reviewed article suggested that a periodic, natural cooling of the Pacific Ocean was counteracting the impact of carbon dioxide.

"1998 was a particular hot year due to a record-breaking El Niño event, while recently we have had mostly the opposite - cool conditions in the tropical Pacific," Prof Stefan Rahmstorf, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, told BBC News.

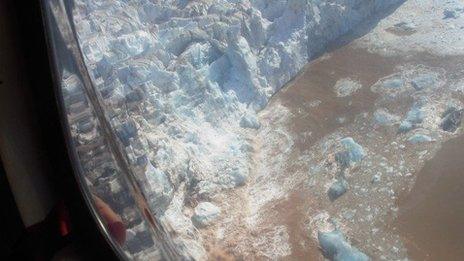

The panel believes that the melting of glaciers and ice sheets is contributing significantly to global sea level rise

"That warming has not stopped can be seen from the ongoing heat accumulation in the global oceans."

Climate sceptics, however, argue that the pause is evidence that climate models used by the IPCC are too sensitive and exaggerate the effects of carbon dioxide.

"In the last year, we have seen several studies showing that climate sensitivity is actually much less than we thought for the last 30 years," said Marcel Crok, a Dutch author who is sceptical of the IPCC process.

"These studies show that our real climate has a sensitivity of between 1.5C and 2.0C. But the models are much more sensitive, and warm up three degrees."

Am I going to get flooded?

The 2007 IPCC report was heavily criticised for its estimations on sea level rise.

The panel suggested that a warming planet would see waters around the world rise by between 18cm and 59cm by the end of this century. Heat causes the seas to expand but also increases the rate of melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

The IPCC figure didn't include any estimates for the extra water coming from the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets as they said they didn't have enough accurate information.

Other researchers were critical, external of this approach and have published studies that suggested a far higher sea level rise.

But in recent months, a study funded by the European Union and involving scientists across the world, came up with what they believe is the most accurate estimate yet - and it increases the level of sea rise by just 10cm from the IPCC report.

"What we are talking about is a reduction in uncertainty - we find we haven't changed the number enormously compared to AR4 (IPCC 2007 report)," said Prof David Vaughan, from the British Antarctic Survey (Bas), while speaking at the launch of the report.

"We've added maybe another 10cm but the level of certainty we have around that is actually higher than it was in the AR4."

Flooding is expected to increase in many parts of the world as a result of rising sea levels

Leaked details from the forthcoming report indicate that the worst sea level rise scenarios for the year 2100, under the highest emissions of carbon dioxide, could reach 97cm.

Some scientists, including Prof Rahmstorf, have been unhappy with the models used by the IPCC to calculate the rise. Using what's termed a semi-empirical model, the projections for sea level can reach 2m. At that point, an extra 187 million people across the world would be flooded.

But the IPCC is likely to say that there is no consensus about the semi-empirical approach and will stick with the lower figure of just under 1m.

So will all this mean more flooding?

"Yes, but not everywhere," said Prof Piers Forster from the University of Leeds. "Generally, the wet regions will get wetter and the dry ones drier."

The report is also likely to assess the intensity of storms, and there might be some better news in that there is likely to be a downwards revision.

And what about the Polar bears?

The state of the North and South Poles has been of growing concern to science as the effects of global warming are said to be more intense in these regions.

In 2007, the IPCC said that temperatures in the Arctic increased at almost twice the global average rate in the past 100 years. They pointed out that the region can be highly variable, with a warm period observed between 1925 and 1945.

In the drafts of the latest report, the scientists say there is stronger evidence that ice sheets and glaciers are losing mass and sea ice cover is decreasing in the Arctic.

In relation to Greenland, which by itself has the capacity to raise global sea levels by six metres, the panel says they are 90% certain that the average rate of ice loss between 1992 and 2001 has increased six-fold in the period 2002 to 2011.

While the Arctic mean sea ice extent has declined by around 4% per decade since 1979, the Antarctic has increased up to 1.8% per decade over the same time period.

As for the future, the suggestions are quite dramatic. Under the worst carbon emissions scenarios, an Arctic free of sea ice in the summer by the middle of this century is likely.

Some recent newspaper reports have suggested, external that sea ice in the Arctic has recovered in 2013, but scientists are virtually certain about the trend.

"The sea ice cover on the Arctic ocean is in a downward spiral," said Prof Rahmstorf. "And much faster than IPCC predicted."

And Prof Shang-Ping Xie from the University of California in San Diego told BBC News that the outlook for polar bears and other species isn't good.

The head of the IPCC Rajendra Pachauri speaking to the media at the launch of the synthesis report in 2007

"There will be pockets of sea ice in some marginal seas. Hopefully, polar bears will be able to survive summer on these pockets of remaining sea ice," he said.

Does the IPCC have a future?

There have been growing calls for reform of the IPCC process from critics and friends alike.

Many believe that these big, blockbuster reports, published once every six years, are not the way forward in the modern era.

"The close government scrutiny and infrequent publication certainly fillip the climate change agenda," said Prof Forster.

"But, given the pace of both science and news, perhaps it is time the IPCC moved with the Twitter generation."

Many sceptical voices are also calling for changes.

Marcel Crok says the whole process of the IPCC is bad for the scientific principle of open argument.

"It is not designed to answer questions because the whole IPCC process, the whole consensus-building process, is choking the openness of the scientific debate," he explained.

However, some argue the IPCC plays an important role as a source of information for developing countries.

And again others think the organisation will survive for far more unprincipled reasons. "It is a UN body," said Prof Petersen. "It may perpetuate until eternity."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published23 September 2013

- Published19 August 2013

- Published19 May 2013

- Published7 March 2013