Rosetta: Riding a ‘bucking bronco’ in space

- Published

- comments

Will Comet Ison break apart in the next few weeks?

The excitement is mounting. We're going to be talking about comets an awful lot in the coming months.

First of all, we have Comet Ison to enjoy. We hope.

This mountain of ice and dust has come hurtling in from the outer Solar System and is about to swing around the Sun.

At closest approach on 28 November, it will be no more than 1.2 million km (800,000 miles) from our star's boiling surface.

The big question is: will it survive the encounter? "Sungrazers" like Ison very often just fall apart. But if it can remain intact, this "dirty snowball" will swing back out past the orbits of the inner planets, potentially throwing off huge streams of gas and dust.

The comet could appear as a great arc across the sky, no binoculars required. Then again, it might not. Comets are notoriously unreliable.

Recent observations have suggested that Ison might fall short of being spectacular, but could still put on a decent show. We won't know for sure until December.

And come December, we'll all have started looking forward to the space mission of 2014: Rosetta.

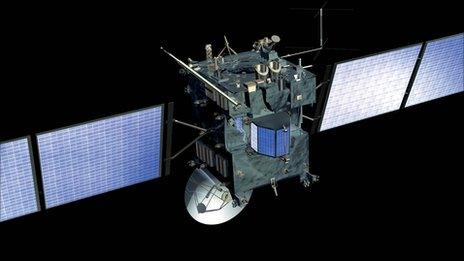

This is the European Space Agency probe that was launched way back in 2004. It's spent the past nine years working its way out to the orbit of Jupiter, to chase down Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

The plan is for Rosetta to circle and track this comet as it sweeps in towards the Sun.

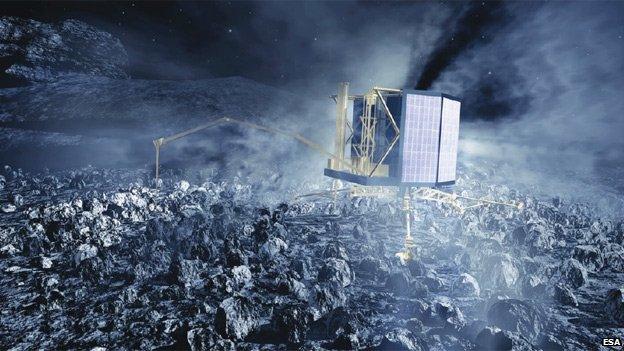

The big highlight, though, will be the deployment of the probe's Philae lander. It's going to try to lock down on 4km-wide 67P and ride it.

How long Philae could withstand any outgassing as the ices heat up on approach to the Sun is anyone's guess. Will 67P be a "bucking bronco"?

"Philae's got screws and harpoons to hold it down," says Dr Matt Taylor, the Rosetta project scientist.

"I have to be confident we'll succeed. We'll be investing a lot of time before the landing trying to find the best place to put down."

Telescopic investigations are encouraging. 67P appears to have three main areas that produce jets, which Philae might want to avoid. But on the whole, the comet's recent passes of the Sun have been relatively smooth - it hasn't been prone to explosive outbursts.

Rosetta is a long way from Earth currently. Probes sent out to the vicinity of Jupiter would usually use radioisotope batteries, but the European spacecraft was equipped only with solar panels.

As a consequence, the probe was put to sleep in 2011 to reduce to its systems' demand for energy.

Controllers at Europe's Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, are not in contact with Rosetta at present.

They're keeping their fingers crossed that an internal alarm clock will rouse the probe on 20 January 2014.

Once awake, it can activate its instruments and prepare for the rendezvous. Needless to say, the alarm clock event has quite a bit of tension associated with it.

"Before turning everything off, we spun up the spacecraft to keep it stable," explains Prof Mark McCaughrean, a senior official in Esa's science directorate.

"At the moment, Rosetta's not pointing its high-gain antenna at the Earth. So, we rely now on that alarm clock going off on time, because if it doesn't we'll have great difficulty communicating with the spacecraft.

"But we do expect it to go off. And when it does, Rosetta will warm up, spin down and point to Earth again, and we will receive a signal. We don't know exactly when we'll receive that signal. It will happen in a window."

Philae will deploy ice screws and harpoons to hold itself down on the comet's surface

Here's a timeline for the key events:

20 January 2014: Wake-up from hibernation

Mid-March 2014: Check-out instruments

21 May 2014: Major rendezvous manoeuvre

6 August 2014: Arrive at Comet 67P

27 August 2014: Start global mapping

11 November 2014: Philae deployment (at about 450 million km from the Sun)

13 August 2015: Perihelion - closest approach to the Sun (at about 185 million km from the Sun)

31 December 2015: Nominal end of mission (although Esa is unlikely to switch off a working Rosetta)

As you can see, it's quite drawn out. We talked of the "minutes of terror" endured waiting for Nasa's Curiosity rover to land on Mars last year. Rosetta is likely to give us months of torture.

Yes, there will be periods of relative inactivity, but there will also be moments of intense drama along the way. The wake-up, the orbit insertion, the Philae landing and the close approach to the Sun could make Rosetta one of the most remarkable missions we've ever seen.

I'm expecting the pictures to be sensational.

The main camera system onboard Rosetta is Osiris (Optical, Spectrocopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System). It has wide-angle and narrow-angle views and will be returning high-resolution perspectives of the comet's icy core, or nucleus. Osiris has already demonstrated its remarkable capability in a pass of Asteroid Lutetia in 2010.

Osiris returned some great pictures of Asteroid Lutetia in 2010

The principal investigator is Holger Sierks from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany.

"We will get thousands of images on approach," he says. "Our [best] resolution is on the order of centimetres and we will be mapping to find suitable landing sites. It is unknown whether we will catch the moment of landing - it is pure speculation right now. But it is our aim to present a movie and to get an image of Philae on the surface."

Rosetta was launched way back in 2004

There's a lot of science to be done, of course.

Comets contain pristine materials from the formation of the Solar System. They give us insights on a time billions of years ago that we cannot get from studying planetary rocks.

"There are many very interesting questions related to comets," explains Dr Jessica Agarwal, also of MPS.

"One is to study whether they brought the water to Earth. It's thought that the water that is now on the Earth is not a remnant from the time of formation of our planet but was delivered later when it was cool enough to retain it.

"Comets are rich in water. One theory is that they may have impacted in large numbers in the past - since they would have been more numerous back then - and could have delivered enough water to fill Earth's oceans. And they may even have delivered organics. These are the things we'd like to understand with Rosetta."

Comets are unpredictable, but occasionally they can put on a great show, as Comet McNaught did in 2007

- Published9 June 2011

- Published10 July 2010