Mars hopper concept 'is feasible'

- Published

- comments

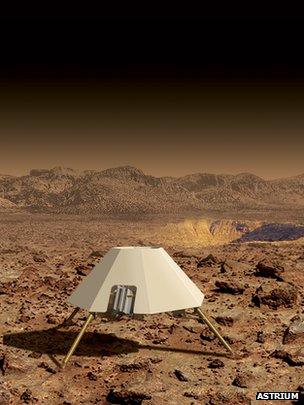

A UK team is developing its idea for a Mars "hopper", external - a robot that can bound across the surface of the Red Planet.

At the moment, landing missions use wheels to move around, but their progress can be stymied by sand-traps, steep slopes and boulder fields.

A hopper would simply leap across these obstacles to the next safest, flat surface.

The research group is led from Leicester University and the Astrium space company.

They propose the use of a vehicle powered by a radioisotope thermal rocket engine.

It would work like this: carbon dioxide would be extracted from the Martian air, compressed and liquefied.

Pumped into a chamber and exposed to the intense heat from a radioactive source, the CO2 would then explosively expand through a nozzle.

Calculations suggest the thrust achieved could enable a one-tonne craft to leap a distance of up to 900m at a time.

"The advantage of this approach is that you have the ability to traverse more aggressive terrains but also that you have wider mobility - the possibility of traversing much greater distances than we have with even the very successful rovers," says Hugo Williams, from Leicester's Space Research Centre, external.

Imagine jumping into and out of craters and canyons, and taking samples from locations that are separated perhaps by many tens of kilometres.

The team first proposed its concept hopper three years ago. Since then, it has been working to refine its ideas.

In particular, the researchers have been putting detail into how the gas compression system would work and how one might go about building the legs.

The latter are a critical aspect of the whole design. Legs on current planetary landers tend to use crushable honeycomb material to dampen the impact at the moment of touchdown.

That's great if you have no intention of moving again, but a hopper would need a resettable landing gear so that it could make multiple landings.

The team has been looking at a system that employs few moving parts and none of the hydraulic fluids found typically in Earth vehicles.

"It's a magnetic system that many people might recall from science lessons at school," explains Mike Williams, a mission systems engineer at Astrium, external.

"When you drop a magnet down a copper tube, you expect it to fall under gravity but it falls very slowly because, as the magnet drops, it creates eddy currents that generate an opposing magnetic field.

"Our legs would use this approach - a very simple, elegant solution that produces a damping effect.

"Nothing is crushed, and there are no fluids, which means we would be very insensitive to the environment and cold temperatures."

The latest phase of research has been funded by the European Space Agency (Esa).

It has sketched out the architecture for a 1,000kg hopper with a leg span of about 4m. The main body would be about 2.5m across.

At this scale, you should be able to carry at least 20kg of science instrumentation.

The study has also thrown up areas that need a lot more work. For example, the system that collects and compresses the CO2 takes several weeks to produce a usable volume of propellant. To be truly practical, the production process needs to be shortened considerably.

"Although we have identified some limitations with various technologies, I think we've demonstrated such a mission is feasible," says Mike Williams.

"Often with these very early and novel concepts, you can show quite quickly that they are totally infeasible. That's certainly not the case here."

The current Curiosity rover is trying to reach a mountain but has to drive around a dangerous sandtrap

Whether we ever see a hopper sent to Mars is another matter.

To date, wheeled rovers and static landers have been doing a great job. And if we do decide to go with another form of locomotion, there are plenty of competing ideas out there, including planes, balloons and even "tumbleweed" devices that would be blown across the Martian landscape in the wind.

But it's the job of scientists and engineers to constantly look over the horizon. In that vein, you'll recall the space penetrator concept for landing on the Jovian moon Europa that I wrote about in July.

"Where the hopper study goes next is difficult to say," Hugo Williams tells me. "But it's important to remember that the reason we do this kind of research is not necessarily to define a single mission concept but to come up with technologies that can be spun out to many other types of space mission or indeed to applications here on Earth."