Nations adopt landmark mercury pollution convention

- Published

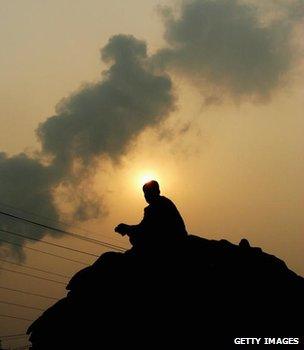

Rising gold prices has seen an increase in small-scale gold mines, most of which use mercury

Nations have begun signing a legally binding treaty designed to curb mercury pollution and the use of the toxic metal in products around the globe.

Mercury can produce a range of adverse human health effects, including permanent damage to the nervous system.

The UN treaty was formally adopted at a high level meeting in Japan.

The Minamata Convention was named after the Japanese city that, in the 1950s, saw one of the world's worst cases of mercury poisoning.

In January, four years of negotiations concluded with more than 140 countries agreeing on a set of legally binding measures to curb mercury pollution.

UN data showed that mercury emissions were rising in a number of developing nations.

The convention regulates a range of areas, including:

the supply of and trade in mercury;

the use of mercury in products and industrial processes;

the measures to be taken to reduce emissions from artisanal and small-scale gold mining;

the measures to be taken to reduce emissions from power plants and metals production facilities.

Earlier this year, the UN Environment Programme (Unep) published a report warning that developing nations were facing growing health and environmental risks, external from increased exposure to mercury.

It said a growth in small-scale mining and coal burning were the main reasons for the rise in emissions.

As a result of rapid industrialisation, South-East Asia was the largest regional emitter and accounted for almost half of the element's annual global emissions, it said.

'Highly toxic'

Mercury - a heavy, silvery white metal - is a liquid at room temperature and can evaporate easily. Within the environment, it is found in cinnabar deposits. It is also found in natural forms in a range of other rocks, including limestone and coal.

Campaigners hope the measures will protect the health of millions of people around the globe

Mercury can be released into the environment through a number of industrial processes including mining, metal and cement production, and the burning of fossil fuels.

Once emitted, it persists in the environment for a long time - circulating through air, water, soil and living organisms - and can be dispersed over vast distances.

The World Health Organization (WHO) says: "Mercury is highly toxic to human health, posing a particular threat to the development of the (unborn) child and early in life.

"The inhalation of mercury vapour can produce harmful effects on the nervous, digestive and immune systems, lungs and kidneys, and may be fatal.

"The inorganic salts of mercury are corrosive to the skin, eyes and gastrointestinal tract, and may induce kidney toxicity if ingested."

The Unep assessment said the concentration of mercury in the top 100m of the world's oceans had doubled over the past century, and estimated that 260 tonnes of the toxic metal had made their way from soil into rivers and lakes.

Another characteristic, it added, was that mercury became more concentrated as it moved up the food chain, reaching its highest levels in predator fish that could be consumed by humans.

Campaigners urged nations to sign the land-mark agreement.

"Millions of people around the world are exposed to the toxic effect of mercury," said Juliane Kippenberg, senior children's right researcher at Human Rights Watch.

"This treaty will help protect both the environment and people's right to health."

- Published21 January 2013

- Published10 January 2013