New 'invisibility cloak' type designed

- Published

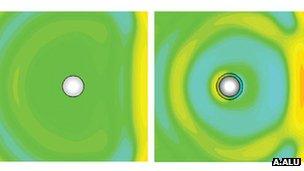

Many "invisibility" techniques actually make objects more obvious, not less, the researchers found

A new "broadband" invisibility cloak which hides objects over a wide range of frequencies has been devised.

Despite the hype about Harry Potter-style cloaks, our best current designs can only conceal objects at specific wavelengths of light or microwaves.

At other frequencies, invisibility cloaks actually make things more visible, not less, US physicists found, external.

Their solution is a new ultrathin, electronic system, which they describe in Physical Review Letters, external.

"Our active cloak is a completely new concept and design, aimed at beating the limits of [current cloaks] and we show that it indeed does," said Prof Andrea Alu, from the University of Texas at Austin.

"If you want to make an object transparent at all angles and over broad bandwidths, this is a good solution.

"We are looking into realising this technology at the moment, but we are still at the early stages."

Passive vs Active

While the popular image of an invisibility cloak is the magical robe worn by Harry Potter, there is another kind which is not so far-fetched.

The first working model - which concealed a small copper cylinder by bending microwaves around it - was first demonstrated in 2006, external.

The sphere on the right is "cloaked" but actually scatters more radiation than when bare (left)

It was built with a thin shell of metamaterials - artificial composites whose structures allow properties which do not exist in nature.

Cloaking materials could have applications in the military, microscopy, biomedical sensing, and energy harvesting devices.

The trouble with current designs is they only work at limited bandwidths. Even this "perfect" 3D cloak demonstrated last year could only hide objects from microwaves.

At other frequencies the cloak acts as a beacon - making the hidden object more obvious - as Prof Alu and his team have now demonstrated in a new study in Physical Review X, external.

They looked at three popular types of "passive" cloaks - which do not require electricity - a plasmonic cloak, a mantle cloak, and a transformation-optics cloak.

All three types scattered more waves than the bare object they were trying to hide - when tested over the whole range of the electromagnetic spectrum.

"If you suppress scattering in one range, you need to pay the price, with interest, in some other range," Prof Alu told BBC News.

"For example, you might make a cloak that makes an object invisible to red light. But if you were illuminated by white light (containing all colours) you would actually look bright blue, and therefore stand out more."

A cloak that allows complete invisibility is "impossible" with current passive designs, the study concluded.

"When you add material around an object to cloak it, you can't avoid the fact that you are adding matter, and that this matter still responds to electromagnetic waves," Prof Alu explained.

Instead, he said, a much more promising avenue is "active" cloaking technology - designs which rely on electrical power to make objects "vanish".

Active cloaks can be thinner and less conspicuous than passive cloaks.

Alu's team have proposed a new design which uses amplifiers to coat the surface of the object in an electric current.

This ultrathin cloak would hide an object from detection at a frequency range "orders of magnitude broader" than any available passive cloaking technology, they wrote.

Nothing's perfect

Prof David Smith of Duke University, one of the team who created the first cloak in 2006, said the new design was one of the most detailed he had yet seen.

"It's an interesting implementation but as presented is probably a bit limited to certain types of objects," he told BBC News.

"There are limitations even on active materials. It will be interesting to see if it can be experimentally realised."

Prof Smith points out that even an "imperfect" invisibility cloak might be perfectly sufficient to build useful devices with real-world applications.

For example, a radio-frequency cloak could improve wireless communications - by helping them bypass obstacles and reducing interference from neighbouring antennas.

"To most people, making an object 'invisible' means making it transparent to visible wavelengths. And the visible spectrum is a tiny, tiny sliver of the overall electromagnetic spectrum," he told BBC News.

"So, this finding does not necessarily preclude the Harry Potter cloak, nor does it preclude any other narrow bandwidth application of cloaking."

Prof Chris Phillips outlines three of the ways to make things invisible

- Published12 November 2012

- Published12 November 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published27 March 2012

- Published26 January 2012

- Published26 September 2011