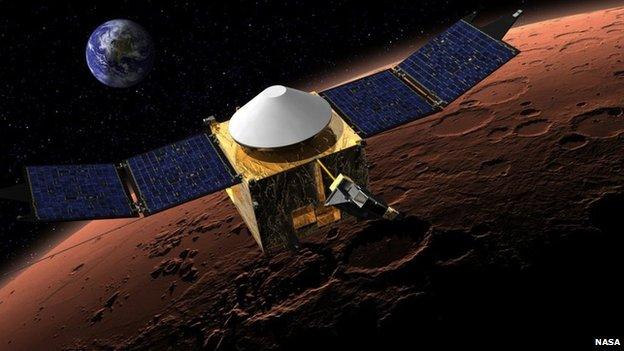

Nasa's Maven mission to study Mars' lost atmosphere

- Published

The Maven orbiter will be like a time machine, reconstructing what the Martian atmosphere was like nearly 4 billion years ago

We know Mars as a dusty seemingly dead planet. But there is growing evidence that it was not always so.

Most planetary scientists believe the Red Planet was once not unlike the Earth. There is evidence that it was once habitable - a world that had a thick atmosphere and water that flowed across its surface.

But around four billion years ago, it is thought that Mars lost its magnetic field - possibly due to a massive asteroid impact.

The field acted as a protective shield against the Sun's corrosive solar wind and without it, the Martian atmosphere was gradually ripped away. So the theory goes.

On Earth, our magnetic field deflects the solar wind and helps contain our atmosphere.

Nasa's Maven spacecraft will orbit the Red Planet to seek further evidence to support this theory.

In particular it will look at the rate at which Mars's now thin atmosphere is continuing to leak away into space.

Once the rate of escape is calculated, it will enable scientists to extrapolate backwards in time and recreate what the Martian atmosphere was once like.

According to Prof Andrew Coates, from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, Maven is essentially a time machine.

"Tying down this escape rate is very important in terms of seeing the history of Mars going back to a time when it probably had an atmosphere could have been habitable," he told me.

Nasa says it is on track to launch its Maven spacecraft on 18 November

The mission sounds simple - but it is not.

In order to reconstruct Mars' ancient atmosphere, scientists need to calculate its likely pressure and composition. They plan to do this by measuring how various components, including carbon dioxide, water and nitrogen, are currently escaping.

Atmospheric escape also varies over time, depending on the natural activity of the Sun.

Earlier missions have taken measurements and the current estimate is that about 10 tonnes of gas is being lost per day. But the uncertainties are large. Maven is unique in that it has been designed to answer this specific question, and so has all the instruments it needs to get the most precise measurements ever obtained of atmospheric escape.

This is what Mars might have looked like before it lost its magnetic field

"We know roughly from previous missions about the amount of material escaping - but they vary wildly," said Prof Coates.

"They can differ by a factor of 10 or 100, depending on which sets of data from which missions you compare. Having all the instruments together on Maven means we will be able to measure it with greater accuracy."

Mars has localised magnetic fields that are thought to be the remnants of the planet's global field. As a result, the planet has faint auroras when cosmic rays batter the planet.

Evidence for their presence was first detected by the European Space Agency's Mars Express mission in 2005 .

It is hoped that Maven may be able to take the first images of the auroras.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published2 October 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published8 April 2013