Bloodhound Diary: The 1,000mph dashboard cam

- Published

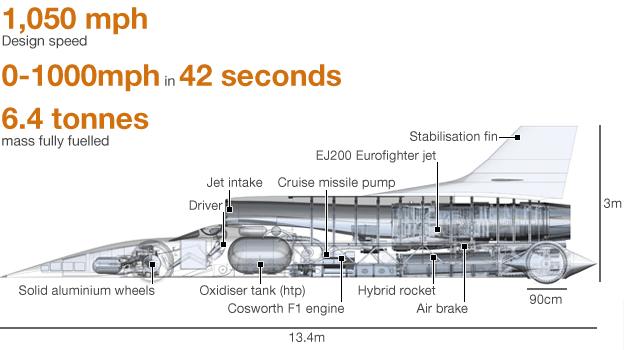

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will mount an assault on the world land speed record. Bloodhound will be run on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2015 and 2016.

Wing Commander Andy Green, world land-speed record holder, is writing a diary for the BBC News website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

Great news from South Africa. The amazing network of high-speed phone masts, built just for Bloodhound, is now complete.

This is a huge commitment from MTN, the mobile phone company providing the network for us. They've built four huge masts, ranging from 15m to 70m tall, and each powered by its own 12kW solar farm, around our track on Hakskeen Pan in the Northern Cape.

Twelve kW is a fair amount of power, enough to boil six kettles, or run 24 refrigerators (and as the desert temperatures vary between freezing in the winter and over 40C in the summer, we'll probably be doing both at some stage).

Six kettles or 24 fridges

These masts are a vital for us, as they give LTE coverage (a sort of 4G high-speed mobile phone service) on the desert. This will allow Bloodhound SSC to transmit HD video and data from the car at over 1,000 mph, to a global audience watching live on the internet.

We're all used to seeing live TV pictures from race cars, like Formula 1, but this is different. The F1 system relies on microwave transmitters, which beam live video directly upwards to helicopters above them.

If you've wondered why there are helicopters tearing around the track at F1 races, this is the reason that they do it. The F1 solution won't work for Bloodhound, though. At 1,000mph, we will be going faster than any aeroplane has ever been at low level.

There is literally nothing in the world that can keep up, so we need a system of fixed masts to capture the video signal. Bloodhound SSC will use aerials on the fin (have you put your name on the Fin yet? 18,000 people have so far) to transmit the signal, using (and I find this bit amazing) about the same power as a mobile phone.

The first mast in the process is positioned about seven miles to the west, at 90 degrees to the track. At this distance out, Bloodhound will remain in a single lobe of the mobile phone signal for the whole 12-mile run, which avoids any breaks in transmission.

Because the mast is positioned at 90 degrees, opposite the centre of the track, the 1,000 mph speed won't cause any Doppler shift. This is the change of frequency caused by high closing/opening speeds, like the drop in engine note as a race car goes past, but multiplied by about 10 times for Bloodhound.

A live feed at 1,000mph

The frequency bands are very narrow and a big Doppler shift could cause the mast to lose the signal, so the location is important.

This signal is then beamed back to Bloodhound's Mission Control Centre for processing, before the remaining two masts relay it south, towards the fibre-optic broadband network over 200km away in the city of Upington. Then it's on its way to you, at home, at school, at work, on your mobile phone.

Bloodhound is a global Engineering Adventure, and the adventure will find you wherever you are, thanks to MTN and our new mast network.

Another key part of Bloodhound's comms is the ability for all team members, spread over 12 miles of desert track, to be able to talk to each other.

This is not as simple as it sounds. We'll be using VHF radios, and VHF signals travel more-or-less in a straight line. However, if you're trying to talk to someone 12 miles away, the curvature of the Earth gets in the way. They are actually over 15m below the horizon, so the VHF signal may not reach them, unless it's relayed through a tall mast.

Here's some more great news this month - a company called Emcom Wireless in South Africa is going to supply all the radios, conduct a full spectrum survey of the desert and provide whatever relay facilities we might need, so that we can all talk to each other - and so that the whole team can all hear the important messages like "Bloodhound is Rolling!"

I've been reading up on the land speed record rules recently, just to make sure we're on top of all the details.

To use the correct terminology, what we are attempting is the Outright World Land Speed Record, external, which is regulated by the FIA.

Possibly the world’s best mobile phone network

It seems strange that we need rules for setting this record, as it is, after all, the simplest form of motorsport - all we have to do is go faster than anyone else, ever. However, history is full of disagreements about who was fastest, because different teams (and countries) had different ideas on how to measure their speed, over what distance, or indeed what constituted a "vehicle".

The record started way back in 1898, with a Frenchman making a one-way run in his electric car at just over 39mph. This was set in a single run, timed over a kilometre with flags and stopwatches.

Quite a gutsy speed for those days, given that a lot of medical advice still said that excess speed would probably lead to the suffocation and death of those involved. Luckily for us, Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat ignored the advice and set his record anyway. Come to think of it, there was quite a lot of "expert" advice telling us that it wasn't possible to go supersonic in 1997 with Thrust SSC, external, but we ignored that as well.

Since that first record in 1898, a number of "rules" have been added and, I think, for the better.

For example, it would be very frustrating to be timing your record attempt over a precisely measured mile, using GPS electronic timing equipment accurate to a millionth of a second, if a rival was using stopwatches over a distance they had paced out on foot. This would be nonsense - but without any rules, what's to stop it happening? Thanks to the FIA, both Bloodhound and all of our competitors, external are working to the same targets, with the same simple rules for setting the Outright World Land Speed Record.

The record must be set in two directions within one hour. The requirement to run in both directions was introduced in 1914, to remove the advantage of cars running downhill with a following wind. This two-way average was initially within 30 minutes which, in the early days, was easy, as the driver would just turn the car around and go again. However, by the 1930s, cars were becoming more complicated and more time was needed.

Gaston bracing himself for 40mph

I suspect it was Sir Malcolm Campbell, holder on nine World Land Speed Records, who got the time extended to one hour.

His 1935 Bluebird car, with 2,300hp and twin rear-wheels, needed more time to change the tyres which were regularly shredded by the power of the car's huge Rolls-Royce engine.

Bloodhound doesn't have to worry about tyres, as we're using solid aluminium wheels, but we do have to check the wheels for damage, change the rocket fuel grain, load 400 litres of jet fuel, 800 litres of rocket oxidiser, replace the cooling water, download and check all of the safety-critical systems data.... the list goes on.

The one-hour turn round will be a big challenge for us, a race in its own right, but it's all part of the adventure. Thanks to MTN's mast network, internet video of the turn round will be relayed live around the world as we do it. That's going to be a nail-biting 60 minutes - make sure you're watching.

We'll be doing our first one-hour "record" turn rounds in South Africa in 2015, so the pressure's on to get the car built over the next year or so. Thanks to BMT HiQ Sigma, we're maintaining a detailed project plan that puts us on the desert in August of 2015, but (as you would expect) the workshop team is determined to beat this figure and get us there earlier. Have a look at Richard Noble's Diary, external for more detail on the planning process.

197kg of engineering perfection

We made another big step in the car's build this month, with the delivery of the rear suspension sub-assembly. This is the huge and complex structure that has to take all of the rear wheels' loads, plus the rocket thrust.

Machined from solid billets, we started with some 2.5 tonnes of aluminium and finished up with 196kg of precision-made components, thanks to over a year's work by the great team at Nuclear AMRC. This set of parts is about 10% of the car's primary structure, so it's a big part of the car's manufacture and build. You can find more pictures of the build process (about 100 of them) on Bloodhound's Storify page, external.

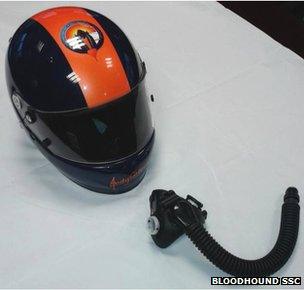

I've also just been to see how CamLock is getting on with the challenge of trying to fit a breathing mask inside a full-face race helmet.

CamLock supplies the Royal Air Force with state-of-the-art masks for our new Typhoon fighters, and the good news is that their low-profile "ADOM" mask fits perfectly inside my Arai helmet. This will guarantee me a supply of clean air throughout every run in Bloodhound, and protect me from any dust in the cockpit, or smoke and fumes if something overheats.

This is a unique solution - as far as I'm aware, no-one has fitted a high-performance mask inside a conventional full-face racing helmet before now.

As always, a key part of Bloodhound is the Education Programme activity. We've got a terrific grant from the Department for Education to deliver 240 days of training courses to teachers over the next 18 months.

This will give them a grounding in what we're planning to do, how we're planning to do it and - most important of all - how to use Bloodhound to make science lessons fun. If your school hasn't already signed up to this free, and exciting, science education project, then have a look at Bloodhound Education, external now and get involved.

Clean air at 1,000mph

We went to the House of Commons this month with the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (a Bloodhound sponsor), to spend four days meeting the politicians and explaining how Bloodhound Education is boosting the nation's interest in science and technology.

To help the process along, we put our visitors (Lords and MPs, we're not fussy) in the Bloodhound Driving Experience so that they could have a go themselves.

My highlight was watching Lord Tebbit setting the fastest time we'd seen, at 1,020mph - he is a former Royal Air Force fighter pilot and he's clearly still got it! The record by the end of the week had been pushed up to 1,026 mph, so clearly it's time to tweak the software and make it more difficult. If you want to try driving Bloodhound yourself, come to one of our public events, external, and let me know how you get on.

Finally, I was lucky enough to be at the annual Rolls-Royce Awards Dinner this month.

The awards recognise individual schools and teachers that deliver great science projects for their students. As you would expect, the Rolls-Royce chief executive highlighted the importance of getting students interested in engineering and science, which is why Rolls-Royce is supporting and sponsoring Bloodhound.

The bit I didn't expect was the next speech, from the head of the Eden Project, Sir Tim Smit.

He apologised, as an environmentalist, for what he was about to say - and then told us that even he was excited about Bloodhound!

His logic was simple, and perhaps the best explanation I've heard of record-breaking. Doing difficult (or impossible) things, just "because it's there", is part of what makes human life exciting. Simple as that. I can't think of a better way of explaining the "adventure" part of Bloodhound's "Engineering Adventure".

Image: Bloodhound SSC

- Published9 October 2013

- Published23 September 2013

- Published3 September 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published4 July 2013

- Published13 May 2013

- Published3 October 2012

- Published7 February 2011

- Published5 March 2011

- Published13 November 2010