Universe measured to 1% accuracy

- Published

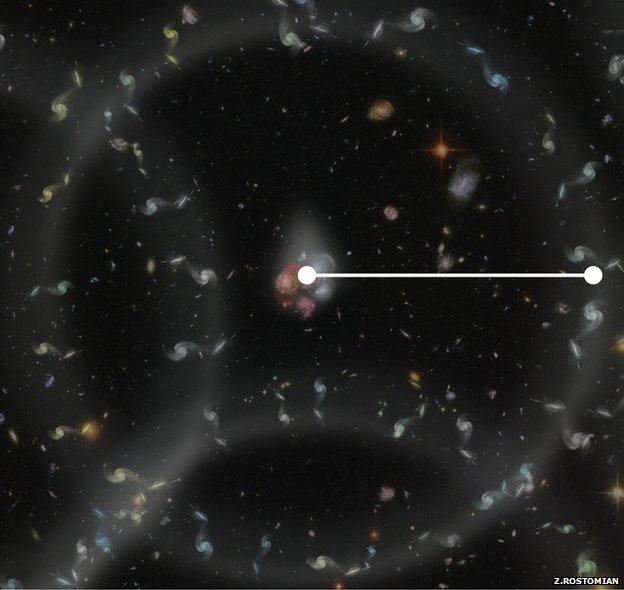

The spheres (BAOs) can be used as a "standard ruler" (white line) to gauge intergalactic distances.

Astronomers have measured the distances between galaxies in the universe to an accuracy of just 1%.

This staggeringly precise survey - across six billion light-years - is key to mapping the cosmos and determining the nature of dark energy.

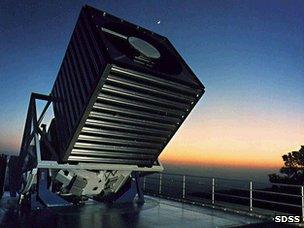

The new gold standard was set by BOSS (the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey), external using the Sloan Foundation Telescope in New Mexico, US.

It was announced at the 223rd American Astronomical Society, external in Washington DC.

"There are not many things in our daily lives that we know to 1% accuracy," said Prof David Schlegel, a physicist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the principal investigator of BOSS.

"I now know the size of the universe better than I know the size of my house.

"Twenty years ago astronomers were arguing about estimates that differed by up to 50%. Five years ago, we'd refined that uncertainty to 5%; a year ago it was 2%.

"One percent accuracy will be the standard for a long time to come."

Frozen ripples

The BOSS team used baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs) as a "standard ruler" to measure intergalactic distances.

BOSS data is acquired by the 2.5m Sloan telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico

BAOs are the "frozen" imprints of pressure waves that moved through the early universe - and help set the distribution of galaxies we see today.

"Nature has given us a beautiful ruler," said Ashley Ross, an astronomer from the University of Portsmouth.

"The ruler happens to be half a billion light years long, so we can use it to measure distances precisely, even from very far away."

Determining distance is a fundamental challenge of astronomy: "Once you know how far away it is, learning everything else about it is suddenly much easier," said Daniel Eisenstein, director of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III.

The BOSS distances will help calibrate fundamental cosmological properties - such as how "dark energy" accelerates the expansion of the universe.

The latest results indicate dark energy is a cosmological constant whose strength does not vary in space or time.

They also provide an excellent estimate of the curvature of space.

"The answer is, it's not curved much. The universe is extraordinarily flat," said Prof Schlegel.

"And this has implications for whether the universe is infinite.

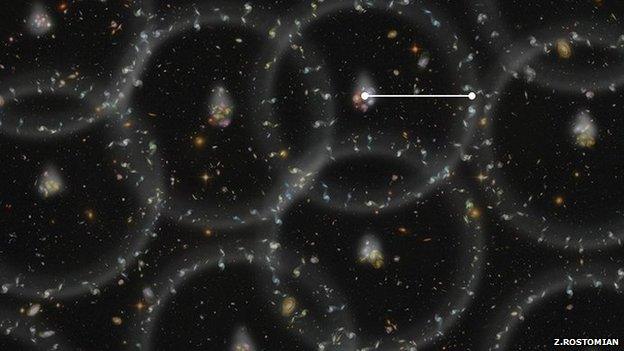

The next challenge is to fill in the gaps - enormous volumes have yet to be mapped

"While we can't say with certainty, it's likely the universe extends forever in space and will go on forever in time. Our results are consistent with an infinite universe," he said.

When BOSS is complete, it will have collected high-quality spectra of 1.3 million galaxies, plus 160,000 quasars and thousands of other astronomical objects, covering 10,000 square degrees.

An analysis of the current data - 90% complete - is published on the Arxiv preprint server, external, with final results expected in June.

After that, future surveys will have to start filling in the enormous gaps between the vast boundaries the BOSS team have defined - and to go much deeper in space. This latter task will be a key objective of Europe's Euclid space telescope due to launch at the end of the decade.

- Published18 September 2012

- Published8 January 2014

- Published13 November 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published31 March 2012

- Published11 January 2011

- Published5 January 2014