Euclid telescope to probe dark universe

- Published

- comments

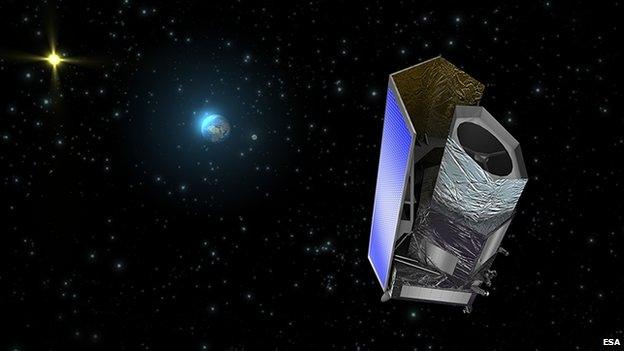

Euclid will conduct its surveys 1.5 million kilometres from Earth on its "night side"

Europe has given the final go-ahead to a space mission to investigate the "dark universe".

The Euclid telescope, external will look deep into the cosmos for clues to the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

These phenomena dominate the Universe, and yet scientists concede they know virtually nothing about them.

European Space Agency (Esa) member states made their decision at a meeting in Paris. Euclid should be ready for launch in 2020.

Esa nations had already selected the telescope as a preferred venture in October last year, but Tuesday's "adoption" by the Science Programme Committee (SPC) means the financing and the technical wherewithal is now in place to proceed.

The cost to Esa of building, launching and operating Euclid is expected to be just over 600m euros (£480m; $760m). Member states will provide Euclid's visible wavelength camera and a near-infrared camera/spectrometer, and its ground and data-handling elements, taking the likely cost of the whole endeavour beyond 800m euros.

The US has been offered, and will accept, a junior role in the mission valued at around 5%. The American space agency (Nasa) will pay for this by picking up the tab for the infrared detectors needed on Euclid. A memorandum of understanding to this effect will be signed between the agencies in due course.

Prof Bob Nichol: This is a big deal for Europe and the UK

"We have negotiated a detailed text with Nasa, which both parties consider final, and it is ready for signature," said Dr Fabio Favata, Esa's head of science planning.

"It will mean a small, commensurate number of US scientists will be welcomed into the Euclid Consortium," he told BBC News.

The consortium is the team that will have access to Euclid's data.

The adoption also will now trigger the release to industry of invitations to tender. Europe's two big space companies - Astrium and Thales Alenia Space - are certain to bid to build Euclid.

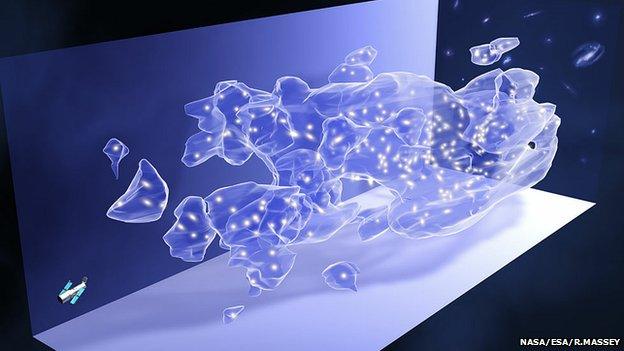

A key task of the telescope will be to map the distribution of dark matter, the matter that cannot be detected directly but which astronomers know to be there because of its gravitational effects on the matter we can see.

Galaxies, for example, could not hold their shape were it not for the presence of some additional "scaffolding". This is presumed to be dark matter - whatever that is.

Although this material cannot be seen directly, the telescope can plot its distribution by looking for the subtle way its mass distorts the light coming from distant galaxies. Hubble famously did this for a tiny patch on the sky, external - just two square degrees.

Euclid will do it across 15,000 square degrees of sky - a little over a third of the heavens.

Dark energy represents a very different problem, and is arguably one of the major outstanding issues facing 21st-Century science.

This mysterious force appears to be accelerating the expansion of the Universe. Recognition of its existence and effect in 1998 earned three scientists a Nobel Prize, external last year.

Euclid will investigate the phenomenon by mapping the three-dimensional distribution of galaxies.

The patterns in the great voids that exist between these objects can be used as a kind of "yardstick" to measure the expansion through time.

Again, ground-based surveys have done this for small volumes of the sky; Euclid however will measure the precise positions of some two billion galaxies out to about 10 billion light-years from Earth.

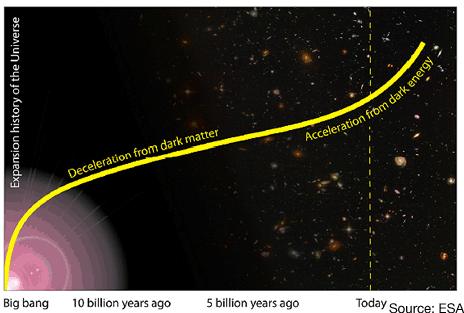

Before 1998's Nobel Prize-winning research, it was assumed gravity was slowing the expansion

Now scientists say the expansion is accelerating, pushing galaxies apart at a faster and faster rate

Euclid's 3-D galaxy maps will trace dark energy's influence over 10 billion years of cosmic history

Euclid was selected as a "medium class" mission, meaning its cost to Esa should be close to 475m euros. The fact that member states are going 125m euros beyond this "guide price" gives an indication of just how highly this mission is regarded.

"Esa have realised this science is so compelling, they just have to do it," said Prof Bob Nichol from the University of Portsmouth, UK.

"They've got a great design and great team, and bravo to them for getting on with it. Every so often you do things that are revolutionary, and Euclid will be one of those transformational missions."

Flying Euclid will give Europe an important lead in a key area of astrophysics.

The Americans would dearly love to fly their own version of Euclid, but there is no money in the Nasa budget currently to make this happen.

The US agency was recently gifted two Hubble-class spy telescopes, external by the National Reconnaissance Office, but even with this donation Nasa is short of the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to turn one of them into a dark mission.

One key design difference between the US concept and Euclid would be the emphasis the American mission would place on using exploded stars, supernovas, as markers to measure the expansion rate of the Universe.

This was the approach used by the Nobel Prize winners (Saul Perlmutter and Adam Riess of the US and Brian Schmidt of Australia). It is not a technique in the primary science of Euclid, but Prof Nichol said it could be deployed at some stage.

Hubble used the so-called "weak lensing" technique to map dark matter in a small patch of sky

"That option is still there and is still being debated," he told me.

"It could be done at the end of the main mission, if we get an extension. We could also do some supernova work during the mission. If certain parts of the sky that we want to look at are not immediately amenable, we could go look for supernovas.

"I believe we could do a fantastic supernova survey, and the Nobel Prize winners are very much involved in how to build such a programme into Euclid. They're brilliant scientists and it would be awesome to have them on board."

Major player

British scientists and engineers will play a key role in Euclid.

The UK will lead the production of the telescope's optical digital camera - one of the largest such cameras ever put in space.

The instrument will produce pictures of the sky more than 100 times larger than Hubble can. This will minimise the amount of "stitching" of images required to build Euclid's maps, making it easier to trace some of the subtle effects astronomers are trying to detect.

When its investments in the Esa portion of the budget and the visible instrument are combined, the UK's total contribution to Euclid comes out at over 100 million euros (£80m).

- Published26 April 2012

- Published31 March 2012

- Published5 October 2011

- Published4 October 2011

- Published4 October 2011