Study doubts quantum computer speed

- Published

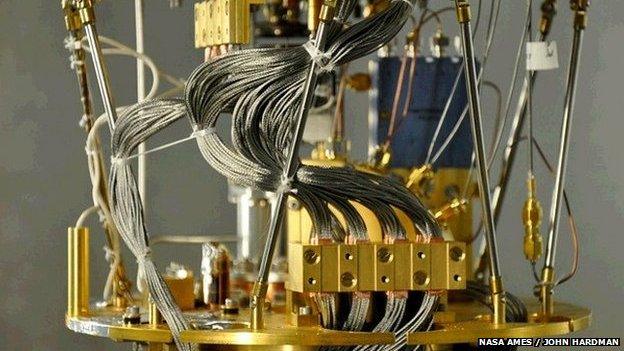

A D-Wave machine has been installed at Nasa Ames Research Center in California

A new academic study has raised doubts about the performance of a commercial quantum computer in certain circumstances.

In some tests devised by a team of researchers, the commercial quantum computer has performed no faster than a standard desktop machine.

The team set random maths problems for the D-Wave Two machine and a regular computer with an optimised algorithm.

Google and Nasa share a D-Wave unit at a space agency facility in California.

The comparison found no evidence D-Wave's $15m (£9.1m) computer was exploiting quantum mechanics to calculate faster than a regular machine.

But the team only looked at one type of computing problem and the D-Wave Two may perform better in other tasks.

The study, external has been submitted to a journal, but has not yet completed the peer review process to verify the findings.

And D-Wave told BBC News the tests set by the scientists were not the kinds of problems where quantum computers offered any advantage over classical types.

Quantum computers promise to carry out fast, complex calculations by tapping into the principles of quantum mechanics.

Daunting challenge

In conventional computers, "bits" of data are stored as a string of 1s and 0s.

But in a quantum system, "qubits" can be both 1s and 0s at the same time - enabling multiple calculations to be performed simultaneously.

Small-scale, laboratory-bound quantum computers supporting a limited number of qubits can perform simple calculations.

But building large-scale versions poses a daunting engineering challenge.

Thus, Canada-based D-Wave Systems drew scepticism when, in 2011, they started selling their machines, which appeared to use a non-mainstream method known as adiabatic quantum computing.

But last year, two separate studies showed indirect evidence for a quantum effect known as entanglement in the computers. And in a separate study released in 2013, Catherine McGeoch of Amherst College in Massachusetts, a consultant for D-Wave, found the machine was 3,600 times faster on some tests than a desktop computer.

Last year, it was announced that Google, Nasa and other scientists would share time on a D-Wave Two - which has a liquid helium-cooled processor operating close to the temperature known as absolute zero - at the US space agency's Ames facility in California.

In the latest research, Prof Matthias Troyer of ETH Zurich and colleagues set random maths problems for a D-Wave machine owned by defence giant Lockheed Martin, pitting it against a desktop machine.

Their results revealed that there were some instances in which D-Wave Two was faster than the "classical" computer, but likewise there were others where it performed more slowly.

Nasa and Google are using the machine to investigate complex problems

Overall, Prof Troyer's team found no evidence for what they call "quantum speedup" in the D-Wave machine.

But Jeremy Hilton, D-Wave's vice-president of processor development, told BBC News: "The 512 qubit processor - used in this recent benchmarking study - was able to meet and match the state-of-the-art classical algorithms and computers even though it has been shown that these particular benchmarking problems will not benefit from a quantum speedup.

"Hence, for this particular benchmark, one does not expect to see a scaling advantage for quantum annealing."

Indeed, in the latest paper, Matthias Troyer and his colleagues write: "Our results for one particular benchmark do not rule out the possibility of speedup for other classes of problems and illustrate that quantum speedup is elusive and can depend on the question posed."

Mr Hilton commented: "An important element of D-Wave's technology is our roadmap and vision. We are laser focused on the performance of the machine, understanding how the technology is working so we can continue to improve it and solve real world problems.

He added: "Our customers are interested in solving real world problems that classical computers are less suited for and are often more complex than what we glean from a straightforward benchmarking test."

D-Wave says it currently has a 1,000 qubit processor in its lab and plans to release it later in 2014.

"Our goal with the next generation of processors is to enhance quantum annealing performance, such that even benchmarks repeated at the 512 qubit scale would perform and scale better. We haven't yet seen any fundamental limits to performance that cannot be improved with design changes," Mr Hilton explained.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published16 May 2013

- Published15 November 2013

- Published13 April 2012