Drug trafficking is speeding deforestation in Central America

- Published

A deforested region in Honduras where drug traffickers are said to operate

A new report says that drug smuggling in Central America is rapidly increasing rates of deforestation.

Remote forests in Honduras and Guatemala are being cut down to facilitate landing strips for the transportation of narcotics.

The scientists believe the influx of drug cash encourages ranchers, timber traffickers and oil palm growers to expand their activities.

The research has been published, external in the journal Science.

Drugs have been smuggled through Central America for decades, with marijuana and cocaine from countries like Colombia heading for lucrative markets in major US cities.

But according to the researchers, the importance of the area as a route for trafficking has increased significantly over the past seven years after a crackdown on the narcotics trade in Mexico.

This prompted drug traders to move their operations into more remote areas in countries like Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Narco effect

The move has seen a rapid increase in the amount of land cleared for forest.

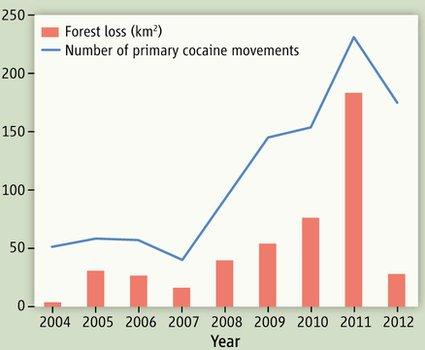

In Honduras, the level of large-scale deforestation per year more than quadrupled between 2007 and 2011, at the same time as cocaine movements in the country also showed a significant rise.

"A baseline deforestation rate in this region was 20 sq km per year," said lead author Dr Kendra McSweeney from Ohio State University.

"Under the narco-effect, we see over 60 sq km per year. In some parts of Guatemala, the rates are even higher. We're talking up to 10% deforestation rates, which is just staggering."

The problems caused by the narcotics trade usually commence with the building of clandestine roads and airstrips in remote forests.

The number of drug-related landing strips prompted Unesco to declare the Rio Platano biosphere reserve in Honduras a "world heritage in danger, external," in 2011.

The number of larger than expected forest clearings in eastern Honduras, indicating a connection to drug trafficking

In both Honduras and Guatemala, these forested areas are often poorly governed. With the influx of new cash and weapons, local ranchers, oil-palm growers and land speculators are emboldened to greatly expand their activities.

Conservation groups are threatened and state prosecutors are bribed to look the other way, says the report.

Laundering profits

The local indigenous populations are often too frightened to speak out.

"Real firebrand indigenous and conservation leaders don't breathe a word of this, out of fear," said Dr McSweeney.

"Honduras now has the world's highest homicide rate. They've all been silenced."

The drug dealers themselves often see advantages in converting the forests into agricultural land.

Buying and clearing the forests helps launder profits, and the traffickers usually have enough political influence to ensure their titles to the land are not contested.

Through this process, the "improved" land can then be sold on to corporate concerns.

In this way, what was once forest is permanently lost to agriculture.

The researchers believe that the attempts by the authorities to declare a "war on drugs" have merely pushed the traffickers into other remote areas, exacerbating pressures on vulnerable and ecologically important forests

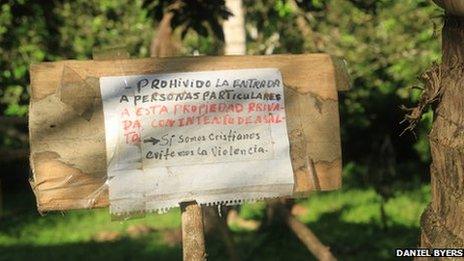

A sign in front of an indigenous farm in Honduras recently overrun by narco-traffickers says: "The entry of persons with violent intent is prohibited. Yes we are Christians and we avoid violence"

"Once you start fighting them, you scatter them into more remote locales and greater areas become impacted, more people get involved and you raise their profits as they put a risk premium on their products," said Dr McSweeney.

"You increase their profits and their need to launder the money."

The authors say that this happened in Honduras in 2012. A crackdown on narcotics has seen the business shift operations and impacts to new areas of eastern Nicaragua.

The report authors argue that conservation groups now need to push for major changes in the use of military force to tackle the problem.

"Conservation groups have big offices in Washington DC and have proven successful at lobbying," said Dr McSweeney.

"We would encourage them to use their clout to really explore alternatives to this appallingly inappropriate, militarised approach to the drug problem."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.

- Published28 January 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published19 December 2013