Hidden history found beneath Alcatraz

- Published

Scientists are uncovering a hidden history lying beneath the prison of Alcatraz

It was America's most notorious prison.

Perched on a rocky outcrop in the middle of San Francisco Bay, from the 1930s to the 1960s the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary was reserved for the "worst of the worst".

A who's who of the criminal underworld were incarcerated there: George "Machine Gun" Kelly, Mickey Cohen and Al Capone all spent time locked up in the tiny cells.

Today, the "escape-proof" jail is a much more accessible place: more than a million tourists visit each year.

But scientists say there's much more to "the Rock" than crime and punishment, and they have come to Alcatraz to investigate the hidden history that lies beneath the prison walls.

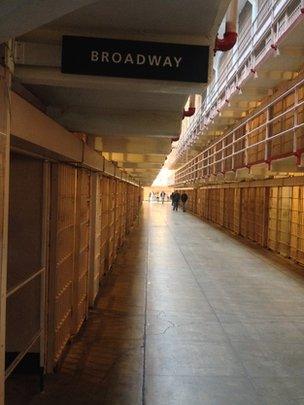

Prisoners were confined to their tiny cells for much of their time on Alcatraz

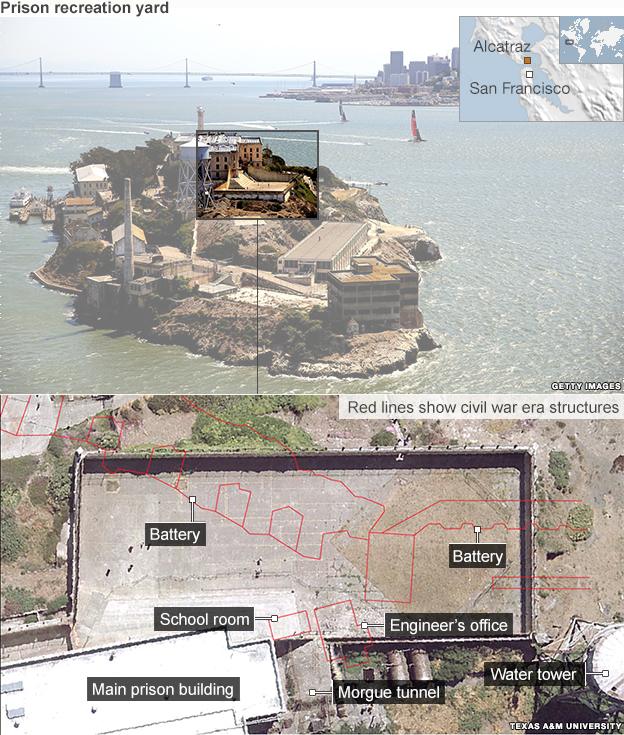

A team from Texas A&M University has gathered in the prison's recreation yard, where inmates would have spent as little as an hour a week away from the confines of the main block.

The researchers are slowly dragging a bright yellow cart along the ground, pulling it up and down in straight lines.

"That's ground-penetrating radar," says Prof Mark Everett.

"The cart has a transmitter and a receiver - it sends an electromagnetic wave into the ground that then reflects off all the different structures underneath.

"Much like medical imaging would make a scan of the body, we are making a scan of the ground under the rec yard."

Using this technique, the team has made a remarkable discovery: they have found the remains of a military fortress, which was thought to have been destroyed.

Standing in the middle of the yard, which is still enclosed by 6m-high (20ft) walls, Prof Everett points to a spot where he has found evidence of a subterranean tunnel system.

"(The tunnels) would have been used for the fortifications. There would have been movement of man and ammunition; it would have been bomb proof and covered with earth so it would have been protected," he explains.

"We get signatures that indicate there is not only a tunnel, but magazine buildings too."

This image, taken in 1868, shows one of the many cannons that formed part of the garrison

The fortress saw little action, and in 1903 it was turned into a military prison

Many traces of the fortress vanished, but some are now being rediscovered using ground-penetrating radar

These structures can be traced back to the 19th Century, at a pivotal moment in US history.

"I think most people know that in 1848 gold was discovered in California, and before that time San Francisco was really a very small town," explains Jason Hagin, the historical architect for the National Park Service, which looks after the island.

"But once gold was discovered here, San Francisco became a very important port for the country and for the west coast, and so protecting it really was the point of building the fortress of Alcatraz."

The island's strategic value became even more important with the outbreak of the American civil war in 1861.

Alcatraz was transformed into a military installation, complete with barracks and gun batteries.

But while much of America was embroiled in bloody battle, the garrison remained quiet and no shots were fired offensively.

At the start of the 20th Century another use was found: Alcatraz was turned into an army prison, paving the way for the federal penitentiary.

The fortress was mainly destroyed or built over, with most traces of it vanishing - until now.

Scientists have found evidence of parts of the fortress lying under the recreation yard

The yard provided prisoners with a brief respite from their time in their cells

"The main prison building was built in about 1915, and we have photographs showing how the rec yard was constructed," says Prof Everett.

"But what we don't really know is what exactly became of the fortifications, what state they are in and what is left of the cultural resources. And although it is not always desirable to excavate, with geophysics we can help people to know what is below the surface without actually disrupting it."

Ground-penetrating radar helps the team to see what lies under the ground without the need to excavate

Joining the team is California State University Chico's Dr Tanya Wattenburg Komas, who is also director of the Concrete Preservation Institute.

Lying beneath the recreation yard is some of the oldest concrete she has ever seen in the US.

"Originally, the fortifications were earthen - they are constructed of dirt - but parts of them had concrete over them to reinforce them. The interesting thing is we weren't even making cement in the US at that time," she explains.

"That probably came as cement in barrels from Europe. To find it on the top of a mid-19th Century battery is very exciting."

She says it's a surprise that it has lasted this long: the conditions on Alcatraz are notoriously tough.

"We are looking at how to preserve this in such an aggressive environment," she says.

"As soon as you are in this misty, wet environment with the salt air, the salt gets in with the water and the oxygen and causes corrosion. And then that produces cracks on the concrete. And once that begins, the deterioration happens very quickly."

Today, the parade ground shows no visible signs of the fortress buildings

Radar tests on the parade ground may show the location of the remains of a large building called a caponier

The biggest potential discovery so far is at the south of the island, lying beneath the prison's parade ground.

"This is an area that is of most historical significance to the park service. It is a very important part of the fortifications," says Prof Everett.

"It is called a caponier, and it is a large structure that juts out into the bay and provides defensive cover. We have seen it in the old photographs but it has completely disappeared from present view."

Using ground-penetrating radar, the team has seen a very large signal, which suggests a large proportion of the building may be buried beneath the ground.

If the team is right, archaeologists will soon start excavations.

"We have a cultural landscape report that proposes to do an excavation on the parade ground," says Mr Hagin. "It's our hope that in the future we can open up the trail and have an archaeological site that people can visit."

He is keen that the rock's military past is brought out into the open.

"The fortification is something that is really important to the historical significance of the island itself," he says.

"In that sense, it is really important to give people a sense of the early part of the island's history."

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published12 June 2012

- Published12 August 2013

- Published19 March 2013