Sentinel satellites promise data explosion

- Published

- comments

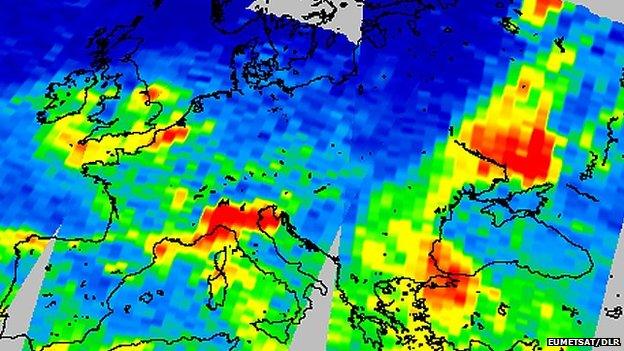

Nitrogen dioxide over Europe: Space monitoring follows through on EU air quality directives

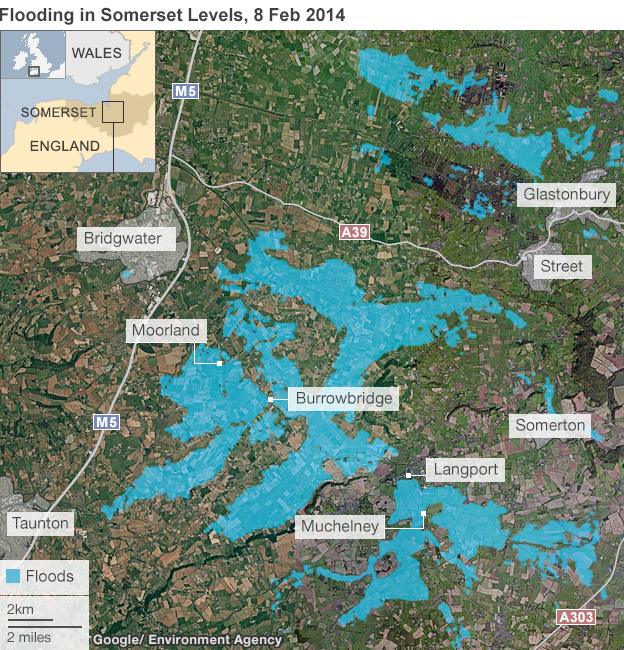

The wettest winter on record in the UK saw the British government take the unprecedented step of activating the International Charter [on] Space and Major Disasters three times in little more than two months, external.

Satellites from many nations were tasked with imaging the magnitude of the flooding in places such as the Somerset Levels.

Particularly useful were the radar pictures. Not only is the presence of extensive water easy to detect in radar images, but this type of observation has the advantage of penetrating cloud.

The data acquired under the charter made it easier for the Environment Agency to see the true scope of the problems it was facing.

From Thursday, there will be a new radar satellite in orbit that will make a significant contribution to the monitoring of any future flooding in Britain and the rest of Europe.

Sentinel-1a, external is the first of a fleet of spacecraft funded under the EU's Copernicus programme, external.

Copernicus is arguably the most ambitious Earth-observation programme for general environmental monitoring ever conceived.

It calls in the first instance for six specific satellites and sensors to be put in orbit, with two copies of each to be flying at any one time.

Consequently, Sentinel-1a will be followed by Sentinel-1b in 2015. As a pair, they will be able to acquire a radar image of anywhere on Earth within six days. In Europe, this will be every day or so.

Although weather satellites have kept a permanent watch on the Earth now for decades, the deployment of general environmental-monitoring spacecraft has been more ad hoc.

There have been exceptions. The American Landsat series of satellites has compiled an unbroken record of the Earth's land surface stretching back 42 years. But even this remarkable project has had to fight tooth and nail with the US Congress every time a spacecraft needed replacing.

Copernicus therefore represents a major step change because the EU has essentially made an open-ended commitment to the Sentinels.

The five further missions to launch between now and 2019 will monitor the oceans, land-change, and the composition of the atmosphere.

Four models of each satellite have already had their funding confirmed. This should take operations deep into the 2030s.

And the Commission and its technical agent, the European Space Agency (Esa), have agreed to start discussions on the requirements for the second half of this century in about 2015/16.

Brussels has several reasons to do this. For one, the information that comes from space-based observations is increasingly needed to design effective policies and to enforce them.

If you are determined to prosecute ship operators that dump oil at sea, you need to catch them doing it. And having a steady stream of radar images of European coastal waters is one of the best ways of doing this.

If you want to set standards for air quality in European cities, you need to monitor the levels of pollutants and track their sources. And having a view from space is important because the wind can blow gases from one member state into another.

So, the EU requires a space dimension to function properly. But Brussels also sees an enterprise opportunity here as well.

It believes space is a domain that can generate significant wealth.

You may have a quizzical look then when you learn that all of the data acquired by the Sentinels will be given away for free, without restriction, to anyone, even if they're outside the EU. And it's a colossus volume - more than eight terabytes a day of processed data when the mature Sentinel constellation is up and running.

But research has concluded that unfettered access will more likely stimulate novel ways to use the data, resulting in the emergence of many more companies, selling new services. For example, more timely radar data from space could soon result in flood forecasting. That is, not merely using the images to see which areas have flooded but using them in smart models to predict which areas will flood next.

A good many of these "value added" services - you can imagine - will end up as apps on citizens' smartphones.

It has been projected that for every euro invested in Copernicus and its Sentinels, a further three euros or so can be generated by new activity. The talk is of about 48,000 new jobs and a boost to the EU's GDP of some 30 billion euros by 2030.

The American Landsat system is a precedent in this sense. Prior to 2008, a price of $600 was charged for every scene. After the fee was removed, the use of Landsat imagery exploded.

"Scientific investigators and resource managers can now use the data they need rather than just the data they can afford," US space agency (Nasa) project scientist Dr Jim Irons told me recently. "As a result, we've seen a revolution in the capacities and methodologies for processing the data. And it's remarkable and exciting to see these folks develop new ways of using the data to visualise the changes taking place on the Earth's land surface."

The EU is hoping for the same from the Sentinels - and then some.

"You can think of our Sentinel-2 spacecraft as a 'super-Landsat'," said Dr Stephen Briggs from Esa's Earth observation directorate.

"It will have more channels, better resolution, and a 280km-swath instead of 180km; and we'll have two of them flying at the same time. And that's just Sentinel-2. All the Sentinels will be an improvement on anything that's gone before. They're a game-changer; Earth observation will never be the same again."

There is something of a data gamble here, however. The enormous dump of free data on the market means current providers that have been charging for this information will now find themselves high and dry.

"Bringing in all this data to stimulate value-added services is great, but it does mean that existing players will see their positions eroded unless they move into new areas," commented Adam Keith, the director of space and Earth observation at industry-watchers Euroconsult, external.

"These companies know that, they know what's coming; and they're starting to shift their business models towards higher resolution systems than the Sentinels, or systems that offer better temporal coverage."

Images from a German radar satellite were used to reveal the full extent of the Somerset floods