Challenge to Titanic sinking theory

- Published

The wreck of the Titanic now lies at a depth of 3,800 m (12,500ft)

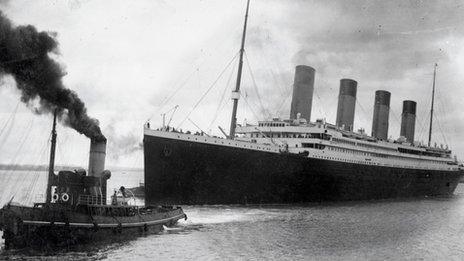

UK scientists have challenged the idea that the Titanic was unlucky for sailing in a year when there were an exceptional number of icebergs in the North Atlantic.

The ocean liner sank on its maiden voyage 102 years ago, with the loss of more than 1,500 lives.

The new analysis found the iceberg risk was high in 1912, but not extreme, as has previously been suggested.

The work by a University of Sheffield team appears in the journal Weather.

The iceberg which sank the Titanic was spotted just before midnight on 14 April 1912, some 500m away. Despite quick action to slow the ship and turn to port, it wasn't enough. About 100m of the hull buckled below the waterline and the liner sank in just two-and-a-half hours.

Reports of unusually bad ice in the North Atlantic started to emerge shortly after the disaster. At the time, US officials told the New York Times that a warm winter had caused "an enormously large crop of icebergs", external.

In the days leading up to that fateful night, the prevailing winds and temperatures, assisted by ocean currents, had conspired to transport icebergs and sea-ice further south than was normal at that time of year.

This iceberg, with a red streak of paint along its side, may have been the one that sank RMS Titanic

All this has led researchers to seek explanations for a supposedly awesome flotilla of ice in the North Atlantic. One US group has proposed that an unusually close approach to Earth by the Moon, external caused abnormally high tides in the winter of 1912, which in turn encouraged a greater than usual amount of ice to break off Greenland's glaciers.

In the latest study, Grant Bigg and David Wilton from Sheffield University's department of geography studied data collected by the US Coast Guard and extending back to 1900.

Observational techniques have changed over the years, complicating comparisons. But the researchers say that a good measure of the volume of icebergs is given by the number that passed the circle of latitude at 48 degrees North, across an area of ocean stretching from Newfoundland to about 40 degrees West.

They found that the record showed great variation in the volume of ice from year to year. And although the iceberg flux from Greenland in 1912 was indeed high, with 1,038 icebergs observed crossing the 48th parallel, this number was neither unusual nor unprecedented.

In the surrounding decades, from 1901-1920, there were five years with at least 700 icebergs crossing 48 degrees North. And the coast guard record shows there was a larger flux of icebergs in 1909 than in 1912.

Prof Bigg told BBC News the flux was at the "large end" but "not outstandingly large" for the first 60-70 years of the 20th Century.

Using the coast guard record and other data, the researchers also developed a computer simulation to examine the likely trajectories of icebergs in 1912. Using this model, they were able to trace the likely origin of the iceberg that sank the Titanic to southwest Greenland.

They suggest that it broke off a glacier in that area in early autumn 1911 and started off as a floating hunk measuring roughly 500m long and 300m deep.

Its mass by mid-April 1912 - as predicted by the computer model - agrees very closely with the size of an iceberg bearing a streak of red paint that was photographed by Captain William Squares DeCarteret of the Minia, a ship that joined the search for bodies and wreckage at the site of the disaster.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published15 April 2012

- Published18 April 2012

.jpg)