Swarm 'delivers on magnetic promise'

- Published

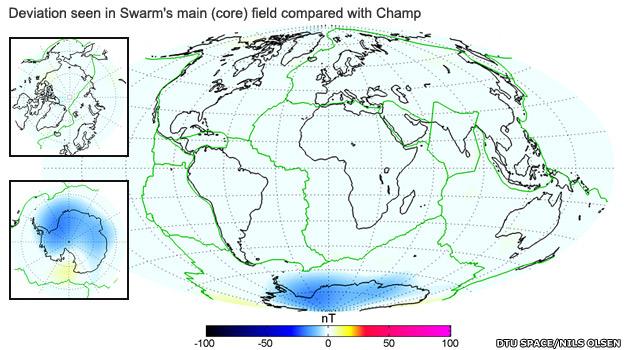

The lack of any colour in this graphic indicates Swarm's model of the global field is already very good

Europe's Swarm mission to measure the Earth's magnetic field in unprecedented detail is achieving impressive levels of performance, scientists say.

Even though the trio of satellites were only launched in November, they are already sensing the global field to a precision that took previous ventures years of data-gathering.

Engineers recently finished all their main commissioning tasks.

They have now put the Swarm constellation in full science mode.

The hope is that the satellites can operate together for perhaps 10 years.

Certainly, their fuel situation is extremely positive thanks to a very accurate orbit insertion by the launch rocket.

“We are on our way; we have very good measurements and we are ready to start accumulating all the data that will provide excellent models for the way the magnetic field is generated by our planet,” said Dr Rune Floberghagen.

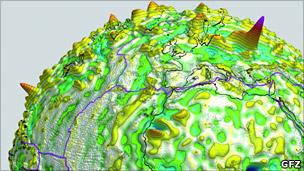

The global field is made up of several components, including the magnetism retained in crustal rocks

The European Space Agency mission manager was providing an update here in Vienna at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly, external.

Earth's magnetic field is worthy of study because it is the vital shield that protects the planet from all the charged particles streaming off the Sun.

Without it, those particles would strip away the atmosphere, just as they have done at Mars.

Investigating the magnetic field also has direct practical benefits, such as improving the reliability of satellite navigation systems which can be affected by magnetic and electrical conditions high in the atmosphere.

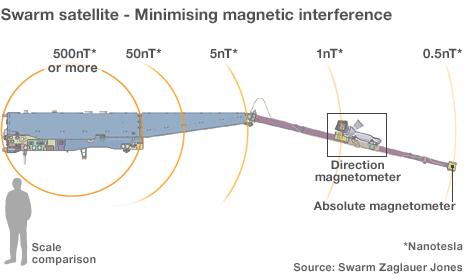

Swarm’s three identical satellites are equipped with a variety of instruments – the key ones being state-of-the-art magnetometers that measure the strength and the direction of the field.

Two of the spacecraft, known as Alpha and Charlie, are currently flying in tandem at an altitude of 462km, and will descend over time.

The third platform, Bravo, has been raised to 510km. A drift has also been initiated that will separate B’s orbital plane from that of A and C during the course of the next few years.

This geometry will enable Swarm to see the field in three dimensions, and to better gauge its variations in time and space.

It will mean the different components in the field can also be teased apart – from the dominant contribution coming from the iron dynamo in the planet’s outer core to the very subtle magnetism generated by the movement of our salt-water oceans.

Describing these features in detail will take a while, but as an early benchmark the science team has assembled a model of the global field, external. It is based on just a few months of magnetometer data gathered in the post-launch commissioning phase.

And it shows that Swarm is providing more or less the same signal as a decade of data from the German predecessor mission known as Champ.

This is illustrated in the image at the top of this page.

“It shows the difference between the Swarm model and the Champ model. And what you see is the model error. Ideally, it should be white all over,” explained Prof Nils Olsen from the Technical University of Denmark.

The fact that the models are in such good agreement so soon was enormously encouraging, he told BBC News.

Engineers are still working a few niggles, which is not unexpected at this stage of a new mission.

For example, a back-up magnetometer on the Charlie platform has failed, perhaps damaged by the intense shaking experienced during launch.

Fully working primary instrumentation means this should not present a problem. But as a precaution, Charlie will now fly in the lower tandem pairing rather than as the lone high satellite, which was originally going to be its role.

Engineers also have some unexpected noise in their data. It is a very small signal but the team told the EGU meeting that they intended to get on top of the issue.

The interference in the magnetic data seems to come and go as the satellites move in and out of sunlight. It is possible that a component inside the spacecraft is evolving its own inherent field as temperatures change.

“It is not so much heating as differential heating that we think may be the problem,” said Prof Olsen.

“It seems on occasions that the Sun is producing some shadows because of features on the spacecraft, and this produces a thermal gradient.

“That’s our current working hypothesis, but I am confident we’ll solve this issue.”

Magnetic "noise" from the satellites' own components has to be understood

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 November 2013

- Published22 November 2013

- Published17 December 2010