Esa's satellite Swarm launch to map Earth's magnetism

- Published

The trio of satellites launched from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, riding a Rockot vehicle

The Swarm mission to map the Earth's global magnetic field in unprecedented detail has launched from Russia.

The trio of European Space Agency (Esa) satellites left the Plesetsk Cosmodrome at 12:02 GMT, riding a Rockot vehicle.

They were deployed at an altitude of 490km, in a polar orbit, 91 minutes later.

Swarm, external's data should help scientists understand better how the field is generated, and why it appears to be weakening.

The strength has fallen by some 15% in the past two centuries. The movement of the north geomagnetic pole has also accelerated.

Researchers have speculated that Earth may be on the cusp of a polarity reversal, which would see the direction of the field flip end to end. North would become south, and vice versa.

This has not happened for 780,000 years, but the phenomenon has nonetheless been a regular occurrence through geological time.

"You could say we're overdue," said Prof Eigil Friis-Christensen, lead proposer on the mission and a former director of Denmark's National Space Institute.

"We talk about the weakening of the global field but in some local areas, such as in the South Atlantic, the field has gone down 10% in just the last 20 years. But we do not know whether we will go into a reversal or whether the global field will recover," he told BBC News.

With their long booms, the satellites have the look of large mechanical rats

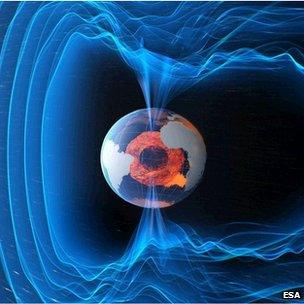

The major part of Earth's global magnetic field is generated by convection of molten iron within the planet's outer liquid core, but there are other components that contribute to the overall signal.

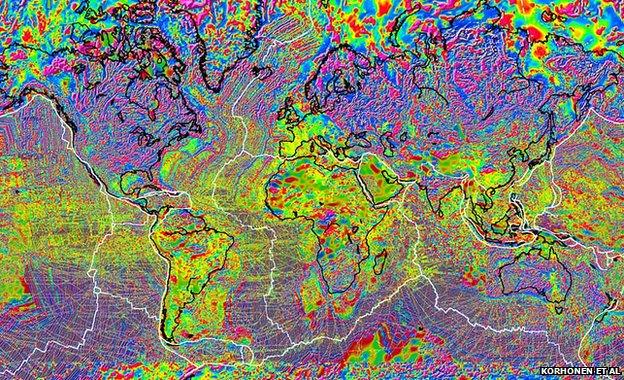

These include the magnetism retained in rocks, and there is even an effect derived from the movement of salt water ocean currents.

Swarm will attempt to tease apart these various factors, to get a clearer picture of the field's true origins and its changing behaviour.

Other uses of the Swarm data will embrace investigations of the electrical environment of the high atmosphere and the way this interacts with the solar wind - the continuous stream of charged particles billowing away from the Sun.

The main component of the global field is generated in the outer core

The wind carries its own magnetic field which clashes with Earth's, producing "storms" that can on occasion disrupt satellites, radio communications and even electricity grids at the planet's surface.

Clean 'rats'

A successful launch was confirmed when the satellites separated from the Rockot's Breeze upper-stage.

Signals confirming their good health were acquired for two of the spacecraft at a ground station in Kiruna, Sweden. The third platform was detected by a station in the Arctic Svalbard archipelago.

This information was relayed to Esa's mission control centre, external here in Darmstadt, Germany, where the operation of the satellites will be managed over the course of the next four years of flight.

All three satellites in the Swarm constellation are identical. Their super-sensitive instrumentation acts rather like a 3D compass, enabling the precise strength and direction of the magnetic field to be determined all around the globe.

The trio's construction was led by the Astrium company, predominantly in Germany and the UK.

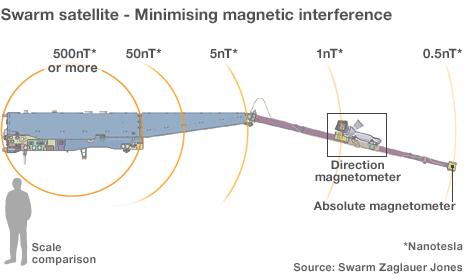

Engineers have had to ensure the magnetism generated by the satellites' own internal electronics does not obscure the mission's subtle scientific measurements.

This has meant putting the instruments on the end of a long boom to keep them separate from the main spacecraft body. It has given Swarm a very distinctive look - like giant mechanical rats with long tails.

The signal introduced by the satellites themselves must be totally understood

A key moment in the coming hours will be the unpacking of the booms. Stowed for launch in a bent configuration, the instrument tails will need to be extended before any data gathering is possible.

"The first boom will open a few hours after launch," explained Andy Jones, the Astrium UK Swarm project manager.

"Each one is held in place by a nut, which will release the boom and allow it to swing open. Springs will initially pull the boom well past the hinge line, and it will then waggle back and forth until eventually settling down. The waggling lasts about a minute and a half."

The Darmstadt space operations team hopes to have all three booms open by early Saturday.

Although Astrium was the industrial prime contractor on the 230m-euro (£190m) project, a host of smaller companies across Europe played their part.

Swarm's ascent actually marked a significant milestone for the British space battery manufacturer, Enersys ABSL.

The Culham, Oxfordshire outfit has now seen more than 100 of its power systems go into orbit.

"We are immensely proud to have contributed to this valuable Esa mission," said director of marketing, David Smart.

"Equally as satisfying is achieving 100 launches which has included exciting and challenging missions to the Moon and Mars, but also to power spacecraft in the new European satellite navigation system."

Swarm is the latest satellite in Esa's Earth Explorer series. Missions have already flown to measure Earth's gravity field, its ice cover, the salinity of its oceans and the moisture retained in its soils. Esa's next Earth observation (EO) launch is likely to be that of Sentinel-1a.

This radar platform will inaugurate the EU's multi-billion-euro Copernicus EO system, external.

"I will receive a review of the current status in December, but I am confident we can launch Sentinel-1a in the spring of next year," Esa director general Jean-Jacques Dordain told BBC News.

Understanding the magnetisation of rocks can reveal information about mineral resources

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 November 2013

- Published7 May 2013

- Published13 February 2013

- Published18 February 2011

- Published17 December 2010

- Published30 June 2010