Wireless pacemaker placed in rabbit

- Published

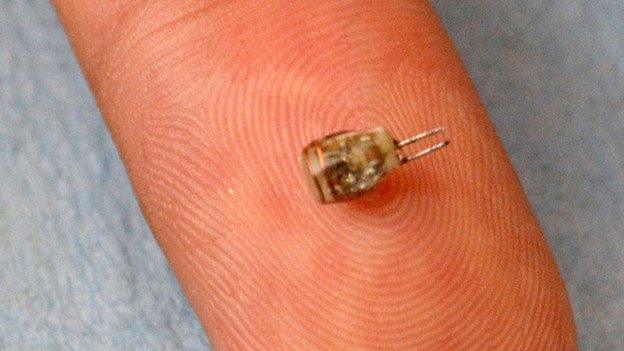

The wireless pacemaker is just 3mm long

US researchers have built a wirelessly powered pacemaker the size of a grain of rice and implanted it in a rabbit.

They were able to hold a metal plate a few centimetres above the rabbit's chest and use it to regulate the animal's heartbeat.

If such medical implants could be made to work in humans, it could lead to smaller devices that are safer to fit.

The findings are published in the journal PNAS, external.

The researchers from Stanford University hope their development could also eventually dispense with the bulky batteries and clumsy recharging systems that are currently a feature of such devices.

The central discovery was a new type of wireless power transfer that could safely penetrate deep inside the body, using roughly the same power as a cell phone.

"We need to make these devices as small as possible to more easily implant them deep in the body," said co-author Dr Ada Poon, from Stanford's department of electrical engineering.

There are broadly two categories of electromagnetic wave that have been considered until now: far-field and near-field.

Far-field waves, like those broadcast from radio towers, can travel long distances, but either bounce off the body harmlessly, or are absorbed as heat.

Near-field waves can be safely used, but they can only transfer power over short distances.

The researchers were able to design a device that blends the safety of near-field waves with the reach of far-field waves.

"With this method, we can safely transmit power to tiny implants in organs like the heart or brain, well beyond the range of current near-field systems," said John Ho, a graduate student in Dr Poon's lab.