Flying robots: Nature inspires next generation design

- Published

Dr Mirko Kovac from Imperial College explains how drones whose design is inspired by nature are set to become part of our everyday lives

Nature is inspiring the design of the next generation of drones, or flying robots, that could eventually be used for everything from military surveillance to search and rescue.

In the journal Bioinspiration and Biomimetics, external, 14 research teams reveal their latest experimental drones.

They include a robot with bird-like grasping appendages, and some that form a robo-swarm or flock.

The developments are inspired by birds, bats, insects and even flying snakes.

Aerial robotics expert Prof David Lentink, from Stanford University in California, says that this sort of bio-inspiration is pushing drone technology forward, because evolution has solved challenges that drone engineers are just beginning to address.

"There is no drone that can avoid a wind turbine," he told BBC News. "And it is very difficult for drones to fly in urban environments," where there are vast numbers of obstacles to navigate, and turbulent airflow to cope with.

Even the humble pigeon, Prof Lentink said, "flies where drones still can't".

Ready to fly

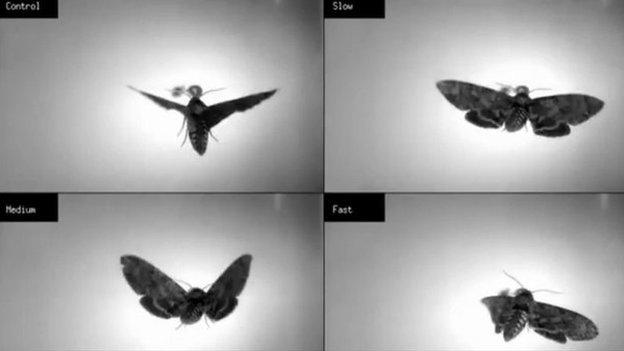

Seeing how moths cope with turbulence in a lab-based whirlwind could aid the design of tiny winged robots

Some advances published in the journal directly demonstrate how these challenges can be overcome.

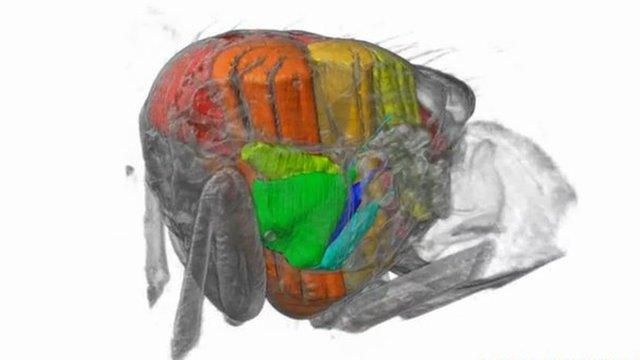

Others simply show, in very fine detail, exactly how flying animals achieve what they do. And such insights - for example, looking at how tiny insects stabilise themselves in turbulent air - will help inform future drone design.

To mimic what Prof Lentink described as insects' "amazing capability of flight in clutter ", one team of researchers, from the University of Maryland, engineered sensors for their experimental drone based on insects' eyes.

With sensors based on insect eyes, a drone is able to navigate through a narrow space

These "eyes" are actually miniature cameras connected to an on-board computer that is programmed to steer the drone away from surrounding objects.

Another team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania has engineered a raptor-like appendage for a drone, enabling it to grasp objects at high speeds by swooping in like a bird of prey.

Among the work focusing on unravelling the mysteries of insect, bird and bat flight, was an experiment by researchers at the University of North Carolina - tethering a moth inside a lab-based tornado chamber.

Footage of the flying insect revealed how it twisted its wings to compensate for the unstable, swirling air.

Another team led by Prof Kenny Breuer at Brown University built an eerily accurate robotic copy of a bat wing, demonstrating the wing's remarkable range of movement and flexibility. This is largely thanks to the thin wing membrane that is unique to bats.

Prof Kenny Breuer from Brown University explains what this eerily realistic robotic wing has revealed about flying mammals' remarkable wings

Membrane-based bat wings are of particular interest to drone engineers, because they are so tolerant of impact.

"They deform instead of breaking," explained Prof Lentink. "They are also adapting better to the airflow because they're so flexible."

'Benefiting humanity'

Dr Mirko Kovac is director of the aerial robotics laboratory at Imperial College, London. His team is currently working on robots that can "perch" on trees and other objects, enabling drones to become "mobile networks of sensors".

"I'm very excited about the future of this field," he told the BBC.

"There are a lot of tasks that we can do with flying robots, such as sensing pollution, observing and protecting wildlife, or we could use them for search and rescue operations after tsunamis."

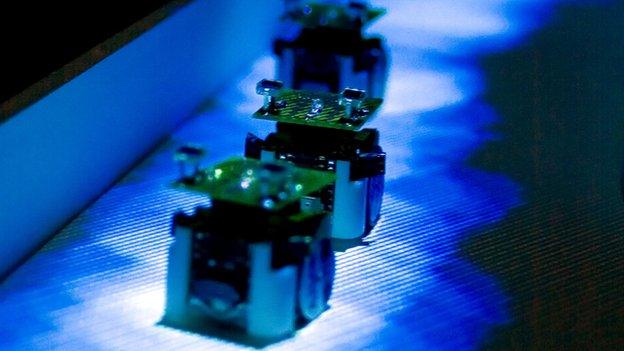

The 'robo-fly', built from carbon fibre, weighs a fraction of a gram

There are already many drones in commercial use. In the UK, for example, the regulator, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), has issued around 50 permissions, essentially drone-operating licences, in just the last year to commercial operators. This allows them to fly their drones in UK airspace.

The vast majority of these are for aerial photography, and current regulations state that drone operators must have visual contact with their vehicle.

A CAA spokesperson told BBC News that, at the moment, "drones could not be allowed to go off and fly out of the operator's sight".

"There isn't the technology in place to allow them to avoid airborne obstacles," the CAA continued, adding that the authority was watching drone development closely in order to "develop regulation in tandem with technology".

And, as these demonstrations highlight, bio-inspired technology is beginning to allow flying robots to do far more than capture footage or pictures from the air.

Dr Kovac commented: "It's important that the applications benefit humanity.

"We must take the responsibility to built robots that are beneficial to society and used in an ethical and positive way."

Prof Graham Taylor from the University of Oxford's animal flight group added that engineers still had a long way to go before they were able to achieve the feats that animals were capable of.

"The depth of our understanding of the biological systems greatly exceeds the depth of our ability to exploit the underlying principles in engineered systems," he explained to BBC News. "So whilst the promise is great, it remains early days for the field."

On its own, each robot would 'just get lost' but as a colony they can navigate

- Published26 March 2014

- Published2 May 2013

- Published29 March 2013