Archaeopteryx: X-rays shine new light on mystery 'bird'

- Published

How the scanning process works

Is it a bird? Is it a dinosaur? Or something in between?

The feathered limbs of Archaeopteryx have fascinated palaeontologists ever since Charles Darwin's day.

Only 12 of these curious creatures have ever been found.

Now these precious fossils are going under the glare of a giant X-ray machine - to find out what lies buried beneath the surface.

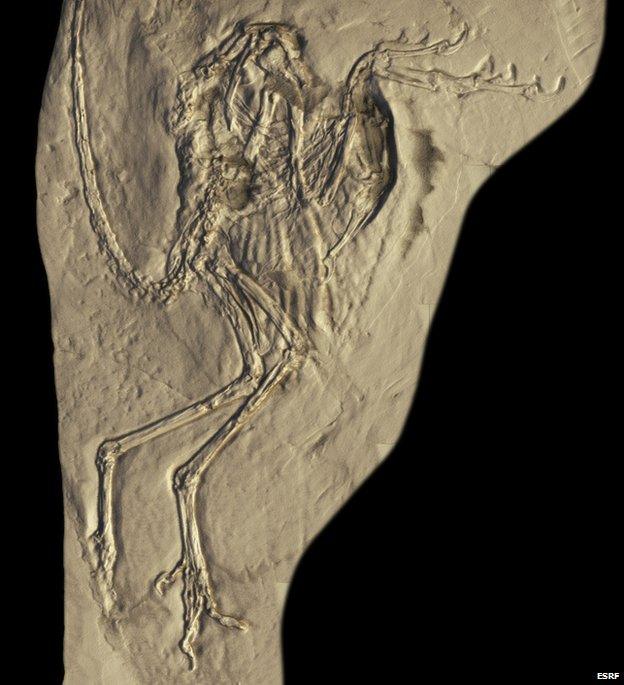

Using a new "camera obscura" technique - inspired by Leonardo da Vinci - scientists have captured some of the clearest ever images of Archaeopteryx.

For the first time, they can see the complete skeleton in 3D. Not just the surface outlines, but all the hidden bones and feathers too.

They hope to discover how "the first true birds" evolved from feathered dinosaurs and took flight.

And what's more, to answer a riddle that has puzzled palaeontologists for 150 years. Could Archaeopteryx fly, or not?

Could Archaeopteryx really fly?

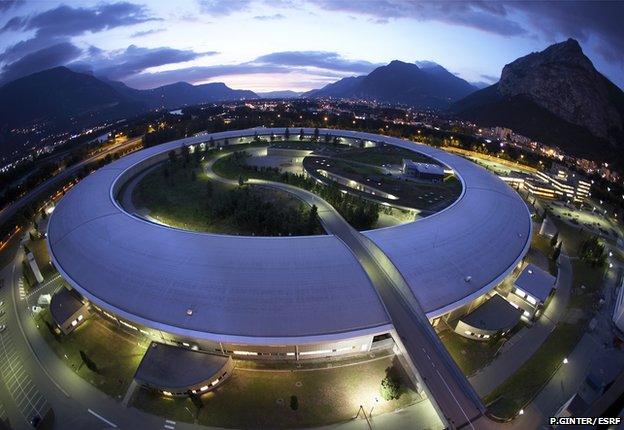

The ESRF is a giant X-ray machine

The new tests are taking place at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, at the foot of the French Alps.

In the past, large fossil slabs were too bulky to be scanned in a synchrotron light source - a type of particle accelerator which generates high-energy X-rays.

But now scientists here are experimenting with a clever new trick, inspired by a very ancient and simple idea - the pinhole camera.

The basic concept has been around since at least 400 BC. But it was Leonardo da Vinci who made the first detailed drawings of a camera obscura in his 1485 sketchbook, Codex Atlanticus.

Light entering through a tiny hole is magnified and projected onto a screen wall.

Leonardo's camera allowed artists inside a tent to accurately trace and paint panoramic landscapes.

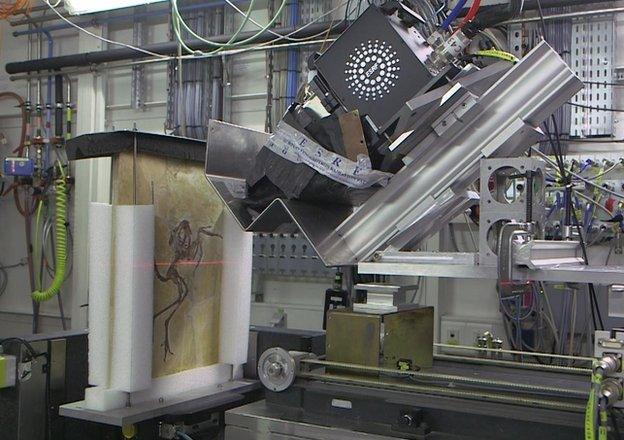

In a synchrotron, the pinhole system allows large fossils - too bulky to be rotated and scanned via conventional techniques (such as tomography) - to be captured in full by an extremely narrow X-ray beam.

"It's a beam that's only the thickness of a human hair. But extremely powerful. If you stood in front of it you would be killed," says Dr Paul Tafforeau, a palaeontologist at ESRF.

"As the beam goes through the sample you have diffusion of the X-rays and this diffusion pattern can be detected via the camera obscura - a very small hole in a piece of lead. Afterwards, you can reconstruct the images in 3D."

The new 3D animation shows Archaeopteryx in a brand new light

The pinhole camera - illustrated by a laser. The real X-ray beam is invisible

If their pinhole trick works as well on all dinosaur fossils as initial tests on Archaeopteryx suggest, it could open up new avenues in fossil research. The world's biggest, most famous dinosaur skeletons could be seen in a whole new light.

And so to demonstrate their proof of principle, the ESRF team began by summoning a very famous specimen.

Archaeopteryx caused a major stir when the first fossil was unearthed in 1861 - just two years after Charles Darwin published On The Origin of Species.

With the claws and teeth of a dinosaur, but the feathers of a bird, it was immediately recognised as a transitional form - proof of Darwin's theory.

Hailed as "the first true bird", the discovery shook the scientific community. Not bad for an animal as small as a magpie - only 20 inches from head to tail.

In recent years, more primitive bird ancestors have been unearthed in Liaoning, China. But the fascination with Archaeopteryx has endured - driven by the unsolved mystery over its ability to fly.

Around 150 million years ago, the modern-day region of Germany where Archaeopteryx lived was an archipelago of islands in a shallow tropical sea, covered in lush vegetation.

Archaeopteryx may have been a flightless predator scurrying among tropical trees

"We want to know how Archaeopteryx lived," says Martin Roeper, curator of the Solnhofen Museum, which houses one of the specimens.

"Was he a little dinosaur running, climbing trees - or was he flying? That's the most important question. Could Archaeopteryx fly or not?"

The answer grows closer as new, microscopic details of its anatomy emerge from ever more precise scans.

Blood vessels within the bones, for example, can be compared to modern birds.

One by one, the 12 fossils have been arriving at the ESRF. And very soon there may be a major breakthrough to announce.

In the meantime: "What is really remarkable are the feathers - they are far more visible by this new scan than by looking at the original specimen," says Paul Tafforeau.

"But that's not all, because this technique reveals a lot about the anatomy that's not visible below the surface.

"You can see many hidden details inside the stone. With these we can better understand what Archaeopteryx really was."

If this X-ray spectacle can be repeated with other famous fossils, there may be other discoveries that ruffle the feathers of established wisdom.

And not only scientists will see the benefit, says Martin Roeper.

"In former times the visitors to our museum cannot easily understand the fossil - because they cannot see the feathers.

"But now that we see the whole wings - now everyone can see that Archaeopteryx really is a very fine specimen."

- Published27 July 2011

- Published1 August 2013

- Published29 May 2013

- Published11 May 2010