Immune children aid malaria vaccine hunt

- Published

The antibody trapped the malaria parasites inside of red blood cells

A group of children in Tanzania who are naturally immune to malaria are helping scientists to develop a new vaccine.

US researchers have found that they produce an antibody that attacks the malaria-causing parasite.

Injecting a form of this antibody into mice protected the animals from the disease.

The team, which published its results in the journal Science, external, said trials in primates and humans were now needed to fully assess the vaccine's promise.

Prof Jake Kurtis, director of the Center for International Health Research at Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine, said: "I think there's fairly compelling evidence that this is a bona fide vaccine candidate.

"However, it's an incredibly difficult parasite to attack. It's had millions of years of evolution to co-opt and adapt to our immune responses - it really is a formidable enemy."

Trapped inside

The study began with a group of 1,000 children in Tanzania, who had regular blood samples taken in the first years of their lives.

A small number of these children - 6% - developed a naturally acquired immunity to malaria, despite living in an area where the disease was rife.

"There are some individuals who become resistant and there are some individuals who do not become resistant," explained Prof Kurtis.

"We asked what were the specific antibodies expressed by resistant children that were not expressed by susceptible children."

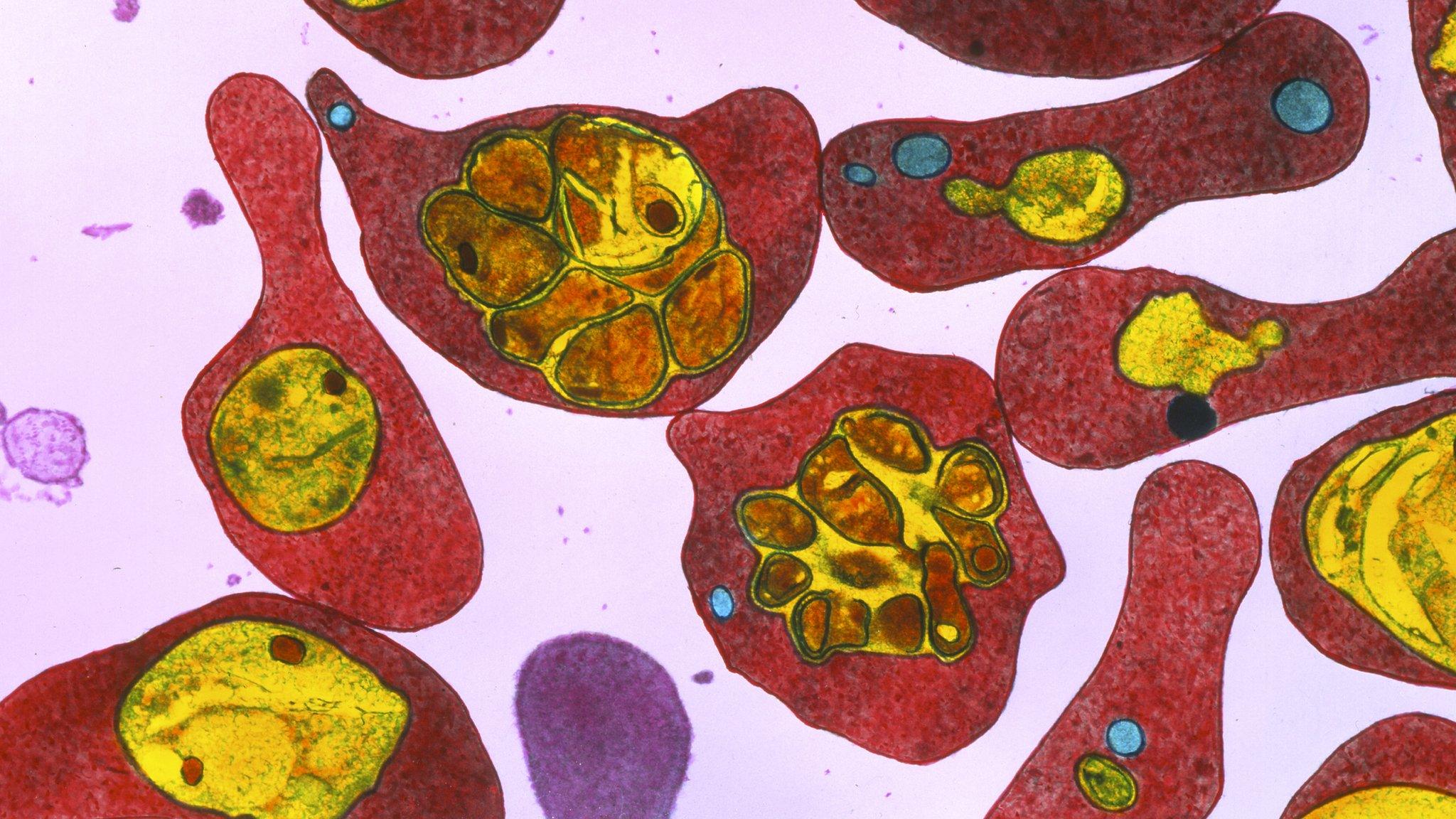

The team found that an antibody produced by the immune children hits the malaria parasite at a key stage in its life-cycle.

It traps the tiny organism in red blood cells, preventing it from bursting out and spreading throughout the body.

Tests, carried out in small groups of mice, suggest this antibody could act as a potential vaccine.

Prof Kurtis said: "The survival rate was over two-fold longer if the mice were vaccinated compared with unvaccinated - and the parasitemia (the number of parasites in the blood) were up to four-fold lower in the vaccinated mice."

The team said it was encouraged by the results, but stressed more research was required.

Prof Kurtis said: "I am cautious. I've seen nothing so far in our data that would cause us to lose enthusiasm. However, it still needs to get through a monkey study and the next phase of human trials."

This latest study is one of many avenues being explored in the race to find a malaria vaccine.

The most advanced is the RTS,S vaccine, developed by GlaxoSmithKline. The drug company is seeking regulatory approval after Phase III clinical trials showed that the drug almost halved the number of malaria cases in young children and reduced by about 25% the number of malaria cases in infants.

Commenting on the research, Dr Ashley Birkett, director of the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, said: "The identification of new targets on malaria parasites to support malaria vaccine development is a necessary and important endeavour.

"While these initial results are promising with respect to prevention of severe malaria, a lot more data would be needed before this could be considered a leading vaccine approach - either alone or in combination with other antigens."

The most recent figures from the World Health Organization suggest the disease killed more than 600,000 people in 2012, with 90% of these deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published8 October 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published7 March 2014

- Published20 December 2011