Ocean waves influence polar ice extent

- Published

The team placed sensors on the floes to track the disturbance caused by ocean waves

Large ocean waves can travel through sea ice for hundreds of kilometres before their oscillations are finally dampened, scientists have shown.

The up and down motion can fracture the ice, potentially aiding its break-up and melting, the researchers told Nature magazine, external.

They say storm swells may have a much bigger influence on the extent of polar sea ice than previously recognised.

The New Zealand-led team ran its experiments off Antarctica.

They placed sensors at various distances from the edge of the pack ice, and then recorded what happened when bad weather whipped up the ocean surface.

For smaller waves, less than 3m in height, the bobbing induced in the floes quickly decayed. But for waves over 3m, the disturbance sent propagating through the pack ice was sustained for up to 350km.

"At the ice edge, it's quite noisy," explained study lead author Alison Kohout, from New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in Christchurch.

"You have lots of waves coming from all directions with a full spectrum of frequencies. But as the waves move into the ice, this all gets cleaned up to produce one beautiful, smooth wave of constant frequency," she told BBC News.

"The ice floes bend with the waves, and over time you can imagine that this creates fatigue and eventually the ice will fracture. Interestingly, the fractures tend to be perpendicular to the direction of the waves, and to be of even widths."

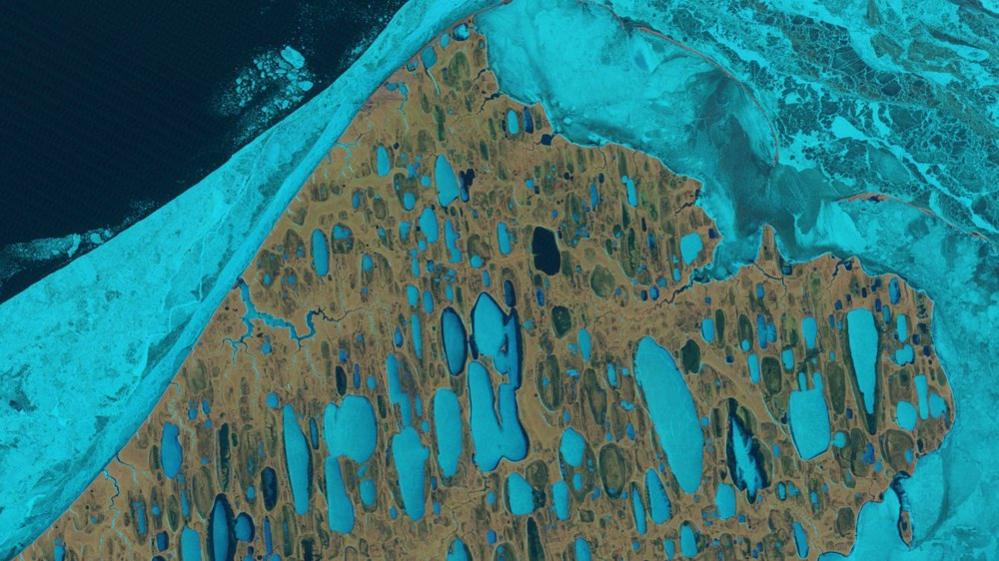

The recent growth in Antarctic sea ice has been a highly regional phenomenon

Computer modellers have been trying to simulate the recent trends in polar sea ice - without a great deal of success.

They have failed to capture both the very rapid decline in summer ice cover in the Arctic and the small, but nonetheless significant, growth in winter ice in the Antarctic.

Dr Kohout and colleagues say their experiments offer some clues - certainly in the south.

When they compared observed Antarctic marine-ice edge positions from 1997 to 2009 with likely wave heights generated by the weather during that period, they found a strong link.

For example, where storminess was increased, in regions like the Amundsen-Bellingshausen Sea, ice extent was curtailed.

In contrast, where wave heights were smaller, such as in the Western Ross Sea, marine ice was seen to expand.

One very noticeable aspect of the recent growth in Antarctic winter sea ice has been its high regional variability.

The team says that if models take more account of wave heights then they may better capture some of this behaviour.

The group did try to look for a similar relationship in storminess and ice extent in the Arctic but found there to be insufficient data to draw any firm conclusions.

The geography at the poles is quite different. The Arctic is in large part an ocean enclosed by land, whereas the Antarctic is a land mass totally surrounded by ocean. Many of the ice behaviours and responses are different as a result.

"I think what's interesting for us in the Arctic is that the 'fetch' is increasing - the distance from the shores to the ice edge is increasing," commented Prof Julienne Stroeve from University College London and the US National Snow and Ice Data Center.

"That would allow the wind to work more on the ocean to produce larger waves that can then propagate further into the ice pack.

"[Another recent paper has already suggested] that wave heights are going to change with increasing distance from the ice edge to the land, and that could have more of an impact on ice break-up."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published19 May 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published9 January 2014

- Published16 December 2013

- Published20 September 2013