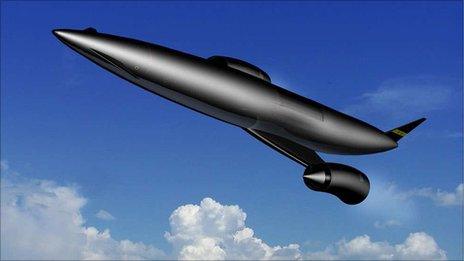

Skylon ‘spaceplane economics stack up’

- Published

- comments

Skylon is the result of 30 years' development and probably about 100m euros (£80m) of investment so far

It appears a feasible proposition, economically. That is the conclusion of a study that considered a European launch service based on a Skylon re-usable spaceplane.

The report, commissioned by the European Space Agency (Esa), was led by Reaction Engines Limited (REL) of Oxfordshire with help from a range of other contractors such as London Economics, QinetiQ and Thales Alenia Space (TAS).

It looked closely at how an operator of the UK-conceived vehicle might meet the demands of its market.

Those requirements would be primarily to loft big telecoms satellites high above the equator of the Earth, but also to put smaller, Earth-observing spacecraft in Sun-synchronous orbits (a type of orbit around the poles). These are the sorts of jobs the Ariane 5 rocket does today, and which Ariane 6, currently under discussion among European governments, may do from the early 2020s onwards.

Skylon is not in that discussion space at the moment - but it may get there at some point in the future if further technical studies prove positive and the financing can be found to push the concept forward.

The Skylon-based European Launch Service Operator (S-ELSO) study examined some of the hardware the vehicle would need to place satellites in orbit, and aspects of the economic model that would allow the operator to turn a profit. It even looked at how the vehicle could work out of Kourou in French Guiana - Europe's spaceport.

In all the areas the study considered, it found positive outcomes. The report was intended to provide Esa with the information it needs to help evaluate what would be a completely different way for Europe to go about its launcher business.

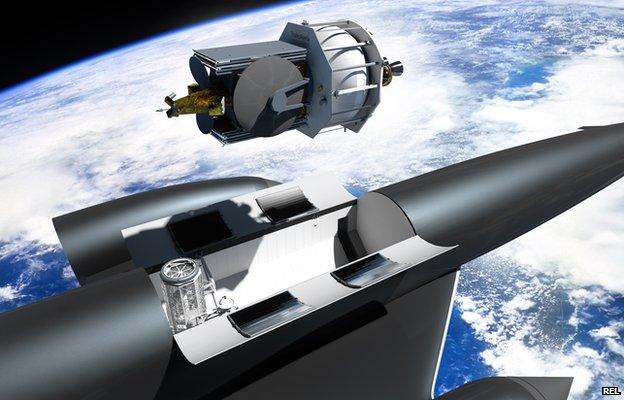

To get telecoms satellites in position, Skylon would deploy a re-usable upper-stage propulsion unit

For starters, Skylon is nothing like the conventional rockets that Europe uses today. Skylon would operate like an aeroplane, taking off from, and returning to, a standard runway.

Traditional rockets dump exhausted boosters and propellant tanks as they ascend

Its technological trick would be its novel propulsion system - power units that work like jet engines at low altitudes and slow speeds, but then transition to full rocket mode at high altitudes and velocities in excess of five times the speed of sound.

This approach, if it can be made to work, would reduce that fraction of the vehicle's mass that must be carried as propellant, enabling the vehicle to take a practical payload to orbit in a single leap.

Although expensive to develop - think of a new Airbus design - it ought to be a good long-term investment because - again, like an Airbus - a Skylon is designed to be used over and over again. Today's rockets can be used just the once.

Indeed, the aviation model is a good one, because the idea as currently envisaged is that there would be a vehicle manufacturer (like an Airbus or a Boeing) that would sell Skylons to many operators (space equivalents of BA, Air France, Lufthansa, etc).

Even though it carries a smaller fraction of propellant, its bulk is still dominated by tankage

The S-ELSO study examined whether a Skylon vehicle could handle the types of payloads governments and commercial interests are likely to want to launch over the next 20 years and more. These include the huge TV-relay, telephony and broadband satellites, the biggest of which could be eight tonnes in mass.

Skylon itself is designed only to go a few hundred km above the Earth, so it would need an additional "upper-stage" module to push the satellite into its final, 36,000km-high orbit.

For the S-ELSO study, TAS was asked to assess this piece of hardware - what it might look like and how it would perform.

It found that the module should have no difficulty putting up all the different types of telecoms satellites, including the new "electric" platforms that use solar power to do some of their own orbit raising and position-keeping.

What it did find, though, was that for the very biggest satellites (eight tonnes), the upper-stage was unlikely to be recovered. It had been an aspiration for Skylon always to try to capture the stage after it had done its job and bring it back to Earth so it too could be re-used.

In a very limited number of cases (for satellites weighing 6.4 tonnes and above), TAS says, this would not be possible. That is about one in 10 cases. In that instance, the upper-stage would be commanded just to destroy itself via re-entry into the atmosphere.

And getting satellites into Sun-synchronous orbits, where a lot of Earth-observing satellites go to picture the planet, is likely to take a different approach to traditional rockets, the study found.

Because Skylon only goes a few hundred km above the Earth, these spacecraft would have to do more of the work themselves to get into their final positions some 800km up - particularly the large ones at four tonnes or more. But with Skylon able to lift seven tonnes to the drop-off point, these satellites could be equipped with much bigger fuel tanks to complete the orbit-raising task.

The study didn't specifically assess the capability, but a Skylon should be able to loft an 11-tonne payload to the space station. It should also be able to put a probe weighing up to two tonnes on an escape path from Earth's gravity to visit other planets.

UK Chancellor George Osborne (second left) sees the Sabre engines as a breakthrough technology

Whether Skylon ever becomes a reality depends in large part on the successful development of its Sabre engines, now in the final phase of design and demonstration with REL. To date, Esa's independent audits have found "no showstoppers".

If the hurdle is crossed - and the UK government is providing £60m to help complete the phase - then a Skylon-like vehicle ought to be producible and flying in the 2020s.

Engine development is in its final phase of design and demonstration

Of course, a key driver is launch prices, and the need to reduce them in order for Europe to stay competitive. Europe's current benchmark target for its next-generation launcher is 70m euros per big telecom satellite.

How much would Skylon launch prices be? That's a "how long is a piece of string?" question. Re-usability and fast turnaround for the operator obviously have a significant downward pressure on prices, but there is also an issue of initial development cost and how that is recovered.

As the S-ELSO document states: "Assuming successful development of the Skylon vehicle, it was found that the S-ELSO business could be economic in exploitation and would be very competitive against a price target of 70m euros. It would also be competitive against the 41.5m-euro price target if there is some level of public support for the Skylon vehicle development programme, which would reduce the vehicle acquisition cost to S-ELSO." (The 41.5m-euro target would be the equivalent of an American Falcon 9 launch according to current SpaceX prices.)

What this means is that Skylon manufacturing and operations could be fully commercial, but some sort of lubrication in the form of a public-private partnership is probably going to be needed.

This touches on the issue of de-risking. The more governments put in at the beginning, the more likely they are to pull in private investors and reduce the overall scale of the financial burden that needs to be recovered - through the purchase price of the spaceplanes and ultimately in the prices they demand to launch satellites.

The model is an aviation one in which an operator might purchase a number of vehicles from a manufacturer

- Published7 August 2013

- Published16 July 2013

- Published28 November 2012

- Published11 July 2012

- Published27 April 2012

- Published24 May 2011