Ebola and ethics: Is animal welfare killing wild apes?

- Published

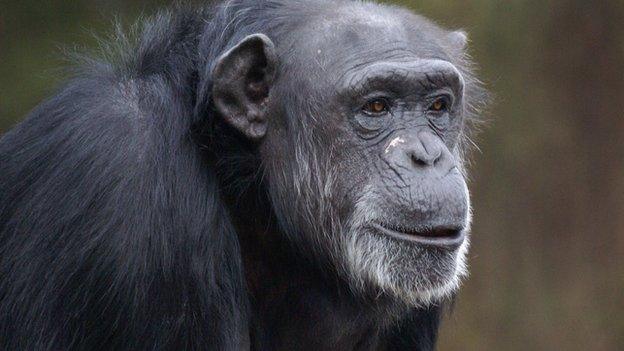

Researchers tested their vaccine on animals housed in a primate centre in the US

The Ebola virus is not just a threat to humans, but is also wiping out chimps and gorillas. Will a decision to end testing on chimps at a major US medical institute hamper efforts to develop a vaccine that could save primates from Ebola?

"Those are samples of gorilla poo, brought all the way from Africa," Peter Walsh announces proudly.

Dr Walsh and his colleagues are studying the samples of centrifuged fecal matter - contained in tiny tubes - in an effort to diagnose and combat the diseases that are threatening our closest and most endangered primate relatives.

One of these diseases is said to be the most frightening on Earth: the Ebola virus.

Ebola has no known cure, is fatal in 90% of cases and is characterised by bleeding, internally and externally.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 300 people have now died in the most recent outbreak of the virus in West Africa.

And, amid this crisis, the same disease is wiping out chimpanzees and gorillas.

"In the last 30 years, [it] has killed about a third of the world's gorillas, and thousands of chimps," says Dr Walsh.

"If we don't do something about this now, these animals are going to go extinct in the wild."

And for Dr Walsh, the solution is straightforward: vaccination. He and his colleagues recently completed the first conservation vaccination trial for chimpanzees , external- testing an experimental Ebola vaccine on a group of chimps at a primate centre in the US - the last developed country where biomedical testing on captive apes is permitted by law.

Chimps in Africa are already dying of Ebola in the wild

But the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), after a detailed consultation on the costs and benefits to public health, has made the decision to retire all but 50 of its research chimpanzees to sanctuaries, external.

"The vaccine trial that we just did might be the last conservation trial on a chimp, because if those labs close down there isn't anywhere else that has the proper facilities to do a vaccine trial," Dr Walsh tells BBC News.

"I would advocate keeping one place that has the capacity to do controlled vaccines trials. "

Sierra Leone has become the latest country to be put on alert over a potential outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus.

But, Beatrice Hahn, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who was on the independent expert advisory panel that recommended the NIH chimps be retired, says there is no need to keep primate centres open to carry out vaccine trials.

"You have to understand that the NIH mission is to improve human health, not chimp health or cat health or dog health," she explains.

"And there may be a better solution to this. One should look to the sanctuaries to potentially do such [conservation] research."

Unlike the NIH, sanctuaries keep chimps for the benefit of the animals. Prof Hahn says that many of them are well equipped and may well be interested in carrying out some of this research.

This, however, would require a change in US law.

The Chimp Act, established in the year 2000, external, states that no chimpanzee in a federal sanctuaries can participate in invasive research. So an animal cannot be injected or have its blood drawn unless it's for its own veterinary care.

But when that law was passed, Prof Hahn points out, it was to prevent sanctuaries from allowing their animals to be used as "furry test tubes" for human medical research. The need for therapies for the conservation of wild apes, she says, changes the legal landscape.

"What also changes the landscape is the increasing endangerment of wild populations. If chimps and gorillas out there in the forest were not endangered, we wouldn't even be talking about it."

Other primate experts are cautious about carrying out research on captive apes.

Steve Ross is the director for the Lester Fisher Center for the conservation of apes at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. He says the challenges of getting vaccines to wild populations in extremely remote areas might never be overcome.

And this issue, he adds, is far more complex than just comparing what's worth more: the welfare of captive animals or the survival of apes in the wild.

"It's a little bit similar to a situation we had in the US 30 years ago where hundreds of chimps were bred up for the study of HIV, but it turned out that chimps were not a good model for that disease," he says.

"If you develop a captive population, test your vaccine and the result is a vaccine that cannot be administered to wild populations and therefore doesn't save a single chimpanzee, we'll have done a tremendous disservice to chimpanzees as a whole."

Catching a cold

Ebola is only one of the infections threatening wild ape populations.

Ironically, some of the conservation tourism programmes that have done so much to raise awareness and money to conserve wild apes are bringing humans close enough to their non-human cousins to pass on infections to which gorillas and chimps have no immunity.

For gorillas exposed to these tourists on a regular basis, human respiratory viruses, including measles, are a major cause of death.

And, just like the thousands of adults and children still dying from measles on the African continent, Dr Walsh says these animals could be vaccinated.

"Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is available from the Centers for Disease Control in the US for $6 a dose," he tells BBC News.

"That means you could take every mountain gorilla in existence, and vaccinate every single one for less than $5,000.

"To hire all the personnel to do it might cost $20,000. And it gives long-term immunity, so you might need to do that every 10-20 years."

Anti-poaching budgets for a park - often involving armed personnel as well as security measures - can run into the hundreds of thousands of US dollars every year.

"So as a cost, it's tiny," says Dr Walsh. "This is the low-hanging fruit, and it gets me so angry to think that chimps and gorillas are dying for silly reasons."

The discussion about if and how to involve captive chimpanzees in the development of vaccines to protect their wild cousins is just beginning. And passions run high.

Something the experts agree on is that disease is a significant threat. And combined with the destruction of habitat and the continuing threat of poaching, time for wild apes is running out.

Follow Victoriaon Twitter, external

- Published18 June 2014

- Published14 October 2013

- Published30 May 2013

- Published15 January 2013