Upgrade for Europe's big X-ray light source

- Published

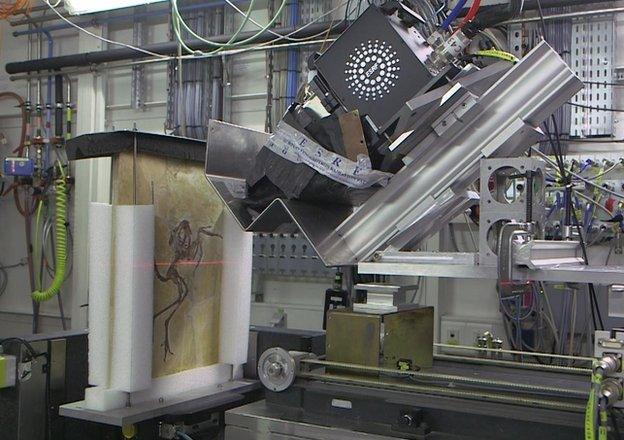

All manner of objects and materials can be put in the X-ray beam to reveal intricate detail

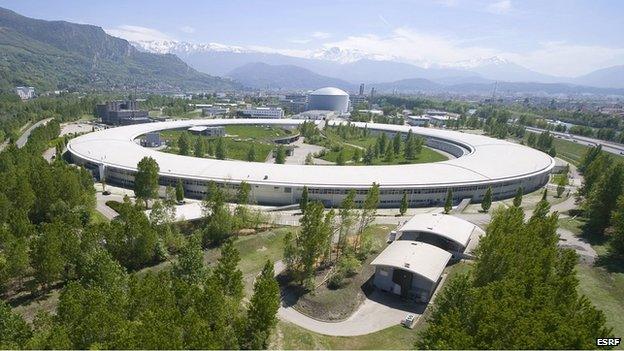

One of Europe's premier scientific research laboratories is to go through a major upgrade.

The improvements to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) will cost some 150m euros (£120m) and take until 2022 to complete fully.

ESRF is essentially a giant X-ray machine, capable of determining the structure of objects and materials at the atomic and molecular scale.

The 850m accelerator ring used to prime these bright X-rays will be replaced.

The scale of the work involved means the facility in Grenoble, France, will have to close for almost two years - from 2018-2020.

But when complete, say officials, the ESRF will be near the physical limits for a "third generation light source" of its size, maintaining Europe's competitiveness at the head of synchrotron science.

"The machine today is the same one that we opened with," said Dr Harald Reichert, the ESRF's director of research.

"But improvements here and there, and regular maintenance, mean it is now a factor of 10,000 times more brilliant than what we started operating with in 1992," he told BBC News.

"To get even more 'horsepower', we now need to replace it, and if we do that we can get up to a factor of 1,000 times more radiation, depending on the energies and applications required."

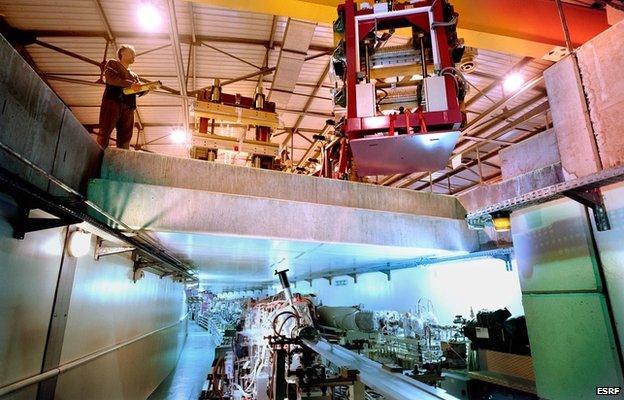

The ESRF produces its X-rays by firing electrons around its 850m circumference, magnetised ring.

As the super-fast electrons bend around this doughnut, they lose a small part of their energy in the form X-rays, which are then funnelled down "beamlines" to penetrate targets positioned in experimental cabins, or "hutches".

The applications for synchrotron science are legion, including the study of biological systems, the probing of fundamental physics, and doing applied chemistry. Archaeologists and palaeontologists will even put their artefacts in the machine.

Next-generation drugs, novel plastics, new ways to prepare and preserve the foods we eat - the advances all come from understanding how atoms and molecules interact. Synchrotrons allow scientists to see this detail.

The big improvements will come from replacing the accelerator ring

ESRF is currently coming towards the end of an initial refurbishment programme, started in 2009 and costing 167m euros, which renewed a lot of equipment.

Certain enhancements to the accelerator also brought an increase in brightness and a greater stability in the X-ray beam.

But the forthcoming replacement of the accelerator ring, taking advantage of the latest magnet designs, known as undulators, will raise the intensity still further.

Key improvements will also enable experiments that rely on finer time-resolution. This would allow scientists to see better molecular systems in action, capturing events that occur in just millionths of a second. An example would be protein behaviour - imaging the "worker" molecules in cells as they perform their functions.

Just over 100m euros of the total upgrade budget will be reserved for the new accelerator ring. A further 20m will go to four new beamlines, and roughly 20m will be spent on an instrumentation programme.

"You can imagine that if we get a new machine with the performance it will have, the data rates we will get out will be just mind-boggling," said Dr Reichert.

"If we don't improve on that side as well, we'll have a machine that spits out so much data no-one can deal with it. So we'll have an instrumentation programme that will include computing to allow us to take full advantage of the improvements."

The latest upgrade will be paid for partly out of ESRF's operational budget, but mostly with new capital from its full and associate member states.

The UK has a 10% shareholding in the light source; France and Germany have a 27.5% and 24% shareholding respectively.

Grenoble science: The synchrotron was built in the foothills of the French Alps

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 May 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published3 September 2013

- Published5 June 2013