Fossil of 'largest flying bird' identified

- Published

The giant bird would have been an elegant flier, able to soar across the ancient ocean in search of food

The fossilised remains of the largest flying bird ever found have been identified by scientists.

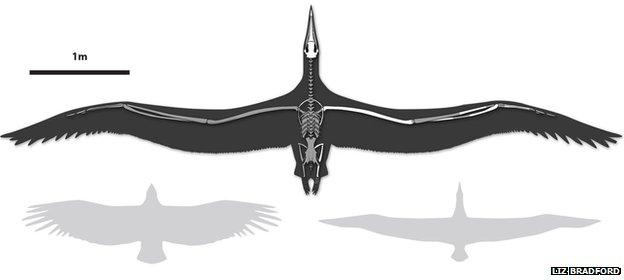

This creature would have looked like a seagull on steroids - its wingspan was between 6.1 and 7.4m (20-24ft).

The find is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

The 25m-year-old fossil was unearthed 30 years ago in South Carolina, but it has taken until now to identify that this is a new species.

Daniel Ksepka, curator of science at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut, said: "This fossil is remarkable both for the size, which we could only speculate on before the discovery, and for the preservation.

"The skull in particular is exquisite.

"And given the delicate nature of the bones... it is remarkable that the specimen made it to the bottom of the sea, became buried without being destroyed by scavengers, fossilised, and then was discovered before it was eroded or bulldozed away."

The researchers believe this huge bird surpasses the previous recorder-holder, Argentavis magnificens - a condor-like bird from South America with an estimated wingspan of 5.7-6.1m (19-20ft) that lived about six million years ago.

The bird would have dwarfed our largest living birds - the California condor (left) and the albatross (right)

Scientists have called the new giant Pelagornis sandersi. They believe it would have been twice the size of the wandering albatross, the largest living bird.

Like the albatross, it was a seabird, spending most of its time swooping above the ocean, preying on fish and squid.

Despite its scale, it would have been an elegant flier.

Bruce Museum curator Daniel Ksepka: Fossil is "spectacular"

While theoretical models suggest that it would be tricky for a bird of this size to stay airborne by flapping its wings, researchers believe it used air currents to soar above the ocean.

Its long, slender wings and light, hollow bones would have made it a powerful glider.

"It would have been fast and very efficient," said Dr Ksepka.

"Computer models suggest that it had high lift-to-drag ratios, which would allow it to glide for a very long distance for every unit of altitude it could attain.

"It could likely glide at speeds over 10m per second - faster than the human world record for the 100m dash."

On land, though, the seabird was probably far less graceful.

"The long wings would have been cumbersome and it would have probably spent as little time as possible walking around," Dr Ksepka explained.

Taking off would also have been an ungainly affair.

Computer models reveal that the bird could not have taken off by simply standing still and flapping its wings.

Instead, scientists think P. sandersi might have had to waddle downhill and hope to catch a gust of air.

Huge birds like this were once common, but they vanished about three million years ago.

Scientists do not yet understand why these giants of the skies died out.

- Published24 November 2010