Boom in satellite ship tracking

- Published

The Fugro Equator has a state-of-the-art multibeam echosounder to map the ocean floor

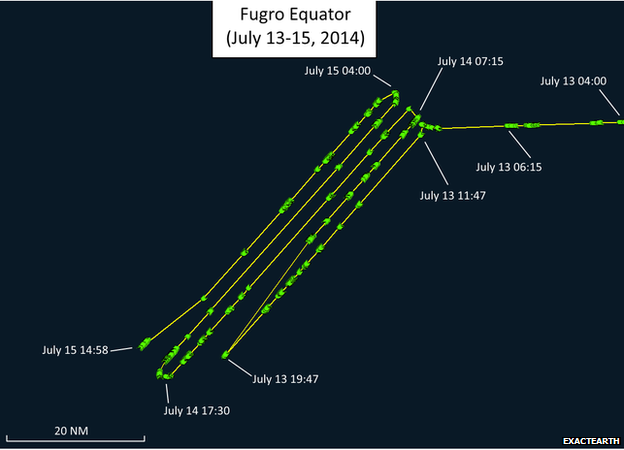

The ship tracks recorded on this map are unmistakably those of a survey vessel moving back and forth on a grid.

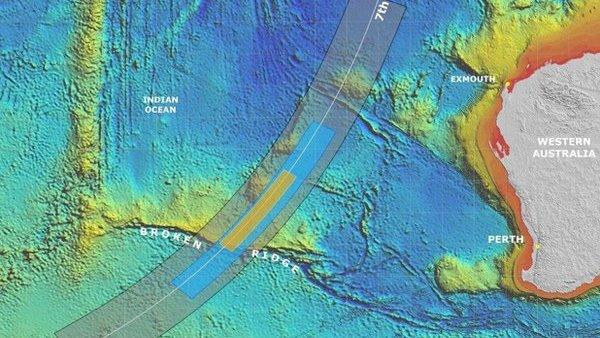

They were produced by Fugro Equator, one of the ships currently making a detailed map of the ocean floor west of Australia as part of the search for wreckage from the lost Malaysia Airlines flight MH370.

The Dutch-owned Fugro Equator, together with the Chinese PLA-Navy ship Zhu Kezhen, which is working further to the south, are gathering bathymetric (depth) data over an area covering some 60,000 sq km.

Once this is in the hands of Australian authorities, the hunt for MH370 will go into a new phase, using a range of submersibles and other deepwater search technologies.

The maps on this page were recorded by exactEarth, one of a growing number of suppliers of ship tracking information acquired from space.

ExactEarth, a subsidiary of Canadian satellite component manufacturer ComDev, has a small constellation of sensors in orbit that can detect the Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals broadcast by ships.

With satellite AIS, ships like Fugro Equator can be tracked anywhere on the oceans

All vessels over 300 gross tons (and all passenger ships irrespective of size) are mandated to carry transponders that push out data that includes not just position, course, and speed, but also information about a ship's type, draught, cargo - even its eventual destination.

AIS was established in the first instance as a safety system - something maritime agencies and ship operators themselves could use to keep tabs on who was doing what in local waters. But the curvature of the Earth means the terrestrial radio network only works within about 75km of the shore, which then requires satellite observation to follow vessels out on the open ocean.

The data has myriad applications including for optimising routing, enforcing fisheries rules, tracing pollution and tackling piracy and smuggling.

ExactEarth is just one company exploiting this new market. This week at the Farnborough International Airshow, it signed a deal to commercialise new detection technology developed within a European Space Agency telecommunications project. The technology will be installed on two satellites to be manufactured by LuxSpace of Luxembourg.

"There are many challenges with satellite AIS since the signals were never meant to be received from space," said Peter Mabson, president of exactEarth.

"The biggest one is that the satellites will receive transmissions from many, many vessels - up to thousands of vessels - simultaneously. So the big challenge is the signal processing challenge of being able to make sense of all that information. From exactEarth's point of view, we have a patented way to do that."

Burgeoning market

Tuesday's contract was signed just a day after Orbcomm, a US rival to exactEarth, put up six new AIS satellites; and a week after a Soyuz rocket lofted separate AIS platforms for the Russian/German satellite builder Dauria Aerospace and for the Norwegian space agency.

The Norwegian platform, AISSat-2, is a follow-up to the highly successful spacecraft the Scandinavian country launched in 2010. Norwegian space agency director-general Bo Andersen credits AIS information, some of it from AISSat-1, for helping to enforce a highly successful cod fishery that has not seen any recorded illegal activity so far this year.

"Norway has the biggest ocean area of any country in Europe," he explains.

"The ocean area is slightly bigger than the whole of the Mediterranean. What's more, it is so far to the north that in summertime, 60% of all the traffic north of the Arctic Circle is in Norwegian waters, and in wintertime it is 90%. And if you go up to the 'real Arctic', which is about 73 degrees North, we see days when all the traffic in the Arctic is in Norwegian waters." An AISSat-3 will be launched in about a year to supplement the observations of all this traffic.

Aviation has a situational awareness system that is similar in many ways to AIS.

It is called Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B). It too will provide identification and tracking information through ground radio networks and satellites. In the case of MH370, however, the ADS-B transponder on the Malaysia Airlines jet was either switched off or failed.

The Fugro Equator has recently returned to its mapping operation after a period in port

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published26 June 2014

- Published26 June 2014

- Published27 May 2014

- Published15 April 2014