Kepler sees world with distant orbit

- Published

The new world completes one orbit of its star every 704 days

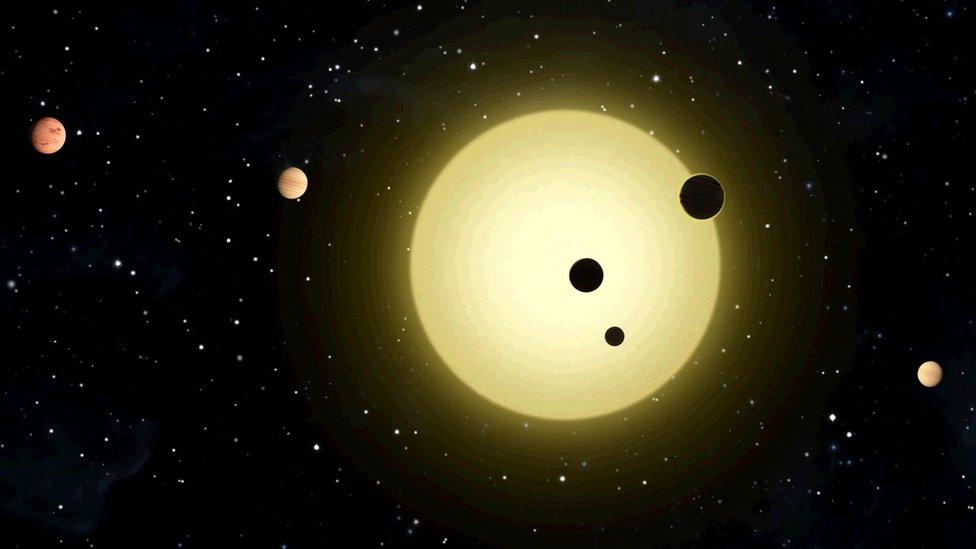

Nasa's Kepler Space Telescope has spotted a distant world with the longest year of any planet in the mission's inventory.

The exoplanet completes one circuit of its parent star every 704 days.

Most of the 1,800 or so confirmed worlds beyond our Solar System orbit much closer to their stars than this one; close-orbiting, large planets are easier to detect.

The study, external is to be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

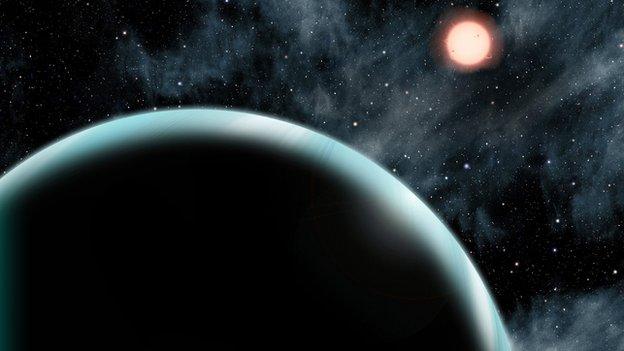

The planet, named Kepler421-b orbits an orange star that is cooler and dimmer than our own Sun. It orbits this host star at a distance of 177 million km (110 million miles).

That's further out than the Earth orbits from the Sun (our planet's average distance is 150 million km) but less than Mars' distance of 228 million km. The Red Planet takes some 687 days to complete one orbit of our host star.

With the information from Kepler, the scientists were able to calculate that the average temperature of the Uranus-sized exoplanet is around -93C (-135F). It orbits a star around 1,040 light-years away,

"Finding Kepler-421b was a stroke of luck," said the study's lead author David Kipping, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, US.

"The farther a planet is from its star, the less likely it is to transit the star from Earth's point of view. It has to line up just right."

The Kepler telescope was uniquely suited to make this discovery: The spacecraft stared at the same patch of sky for four years, watching for stars that dim as planets cross in front of them. This technique for discovering exoplanets is known as the transit method.

Despite this, the space observatory only detected two transits of Kepler-421b due to the planet's long orbital period.

The distant world's orbit places it outside the "snow line" - the line in space that divides rocky planets like Earth from the gas giants like Jupiter. Beyond this line, water condenses into ice grains that stick together to build gas planets.

"The snow line is a crucial distance in planet formation theory. We think all gas giants must have formed beyond this distance," Dr Kipping said.

Since gas giants can be found extremely close to their stars, in orbits lasting days or even hours, theorists believe that many exoplanets migrate inward early in their history.

Kepler-421b demonstrates that this planetary migration isn't necessary; the planet could have formed exactly where it currently is.

The ability to discover planets this distance from their host stars is crucial for understanding the diversity of planetary systems beyond our own.

- Published26 February 2014